The Concord Museum in Concord, Massachusetts, has an extensive collection of artifacts from Concord’s Native American, Colonial, Revolutionary and 19th century history. The town’s pivotal role in the opening salvos of the War of Independence, the Battles of Lexington and Concord, is represented by, among other treasures, the lantern Paul Revere had hung in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church to warn the colonial militia that the British regulars were coming by land, and the Amos Barrett powder horn which was used at the Battle of Concord on April 19th, 1775.

The Concord Museum in Concord, Massachusetts, has an extensive collection of artifacts from Concord’s Native American, Colonial, Revolutionary and 19th century history. The town’s pivotal role in the opening salvos of the War of Independence, the Battles of Lexington and Concord, is represented by, among other treasures, the lantern Paul Revere had hung in the steeple of Boston’s Old North Church to warn the colonial militia that the British regulars were coming by land, and the Amos Barrett powder horn which was used at the Battle of Concord on April 19th, 1775.

Concord is just as prominent in 19th century literary history. Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose father was raised in Concord, moved there in 1835 and his circle of Transcendentalist writers and thinkers grew around him. The likes of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Louisa May Alcott wrote seminal works as part of Emerson’s Concord crew.

It’s Henry David Thoreau, however, who left his greatest mark on Concord and its museum. He was one of Emerson’s circle, but he didn’t follow him to Concord; Thoreau was a native Concordian, the son of a local pencil maker father and committed abolitionist mother. Their family home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Walden Pond, where he lived in a little cottage for two years and wrote his seminal work Walden is in Concord. He wrote Civil Disobedience after spending a night in Concord jail for refusing to pay taxes in protest of slavery.

It’s Henry David Thoreau, however, who left his greatest mark on Concord and its museum. He was one of Emerson’s circle, but he didn’t follow him to Concord; Thoreau was a native Concordian, the son of a local pencil maker father and committed abolitionist mother. Their family home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Walden Pond, where he lived in a little cottage for two years and wrote his seminal work Walden is in Concord. He wrote Civil Disobedience after spending a night in Concord jail for refusing to pay taxes in protest of slavery.

Unlike Emerson’s, Thoreau’s writings were largely dismissed during his lifetime, especially his political essays which would have such a profound influence on world-changing figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi. His writings on natural history, primarily Walden, got more attention, but they received mixed reviews at best. Even though his friend and literary luminary Ralph Waldo Emerson delivered the eulogy at his funeral after he died of tuberculosis in 1862, Thoreau didn’t even get his own individual obituary. It was lumped in with a group of other people who had recently died.

His younger sister Sophia, an accomplished botanist whose precision and artistry in mounting specimens was and is staggering, took on the responsibility of maintaining her brother’s legacy. They had been very close — Thoreau was no social butterfly and could be a cantankerous cuss even with his close friends, but he was a loving and warm sibling — and enjoyed their shared interest in naturalism. He recorded several times in his journals that she had discovered botanical specimens he’d never seen before. Her particular skill was in pressing and attaching plants to a backing sheet with strips of paper that were entirely invisible once she was done. They were so good that a professional like Louis Agassiz, Harvard’s first professor of botany, acquired some of Sophia’s specimens. Several of her specimens now in the Concord Museum include tributes to great authors including Emerson, Shakespeare, and of course her beloved brother. She wrote verses from their poetry in ink on pressed leaves.

His younger sister Sophia, an accomplished botanist whose precision and artistry in mounting specimens was and is staggering, took on the responsibility of maintaining her brother’s legacy. They had been very close — Thoreau was no social butterfly and could be a cantankerous cuss even with his close friends, but he was a loving and warm sibling — and enjoyed their shared interest in naturalism. He recorded several times in his journals that she had discovered botanical specimens he’d never seen before. Her particular skill was in pressing and attaching plants to a backing sheet with strips of paper that were entirely invisible once she was done. They were so good that a professional like Louis Agassiz, Harvard’s first professor of botany, acquired some of Sophia’s specimens. Several of her specimens now in the Concord Museum include tributes to great authors including Emerson, Shakespeare, and of course her beloved brother. She wrote verses from their poetry in ink on pressed leaves.

Their bond and love of nature is sweetly illustrated in this passage from Thoreau’s journal dated May 22, 1853.

When yesterday Sophia and I were rowing past Mr. Prichard’s land, where the river is bordered by a row of elms and low willows, at 6 P.M., we heard a singular note of distress as if it were from a catbird — a loud, vibrating, catbird sort of note, as if the catbird’s mew were imitated by a smart vibrating spring. Blackbirds and others were flitting about, apparently attracted by it. At first, thinking it was merely some peevish catbird or red-wing, I was disregarding it, but on second thought turned the bows to the shore, looking into the trees as well as over the shore, thinking some bird might be in distress, caught by a snake or in a forked twig. The hovering birds dispersed at my approach; the note of distress sounded louder and nearer as I approached the shore covered with low osiers. The sound came from the ground, not from the trees. I saw a little black animal making haste to meet the boat under the osiers. A young muskrat? a mink? No, it was a little dot of a kitten. It was scarcely six inches long from the face to the base — or I might as well say the tip — of the tail, for the latter was a short, sharp pyramid, perfectly perpendicular but not swelled in the least. It was a very handsome and precocious kitten, in perfectly good condition, its breadth being considerably more than one third of its length. Leaving its mewing, it came scrambling over the stones as fast as its weak legs would permit straight to me. I took it up and dropped it into the boat, but while I was pushing off it ran to Sophia, who held it while we rowed homeward. Evidently it had not been weaned — was smaller than we remembered that kittens ever were — almost infinitely small; yet it had hailed a boat, its life being in danger, and saved itself. Its performance, considering its age and amount of experience, was more wonderful than that of any young mathematician or musician that I have read of.

Sophia edited The Maine Woods, a collection of articles he’d written about his travels in what was then an unspoiled wilderness, and Cape Cod and saw them through publication. She also preserved Thoreau’s belongings, manuscripts and journals. Practically everything of Thoreau’s in museums and collections today is a result of Sophia’s commitment to her keeping her brother’s memory and literary legacy alive.

Sophia edited The Maine Woods, a collection of articles he’d written about his travels in what was then an unspoiled wilderness, and Cape Cod and saw them through publication. She also preserved Thoreau’s belongings, manuscripts and journals. Practically everything of Thoreau’s in museums and collections today is a result of Sophia’s commitment to her keeping her brother’s memory and literary legacy alive.

Today the Concord Museum has the largest collection of Thoreau-related objects in the world. More than 250 pieces of his furniture, glassware, books, pictures, manuscripts, pottery and textiles are in the Concord Museum, including the green pine desk on which he wrote Walden and Civil Disobedience. Fully half of the objects in the Concord Museum’s Thoreau collection came directly or indirectly from Sophia. The rest came from donations and purchases over the past 50 years.

Today the Concord Museum has the largest collection of Thoreau-related objects in the world. More than 250 pieces of his furniture, glassware, books, pictures, manuscripts, pottery and textiles are in the Concord Museum, including the green pine desk on which he wrote Walden and Civil Disobedience. Fully half of the objects in the Concord Museum’s Thoreau collection came directly or indirectly from Sophia. The rest came from donations and purchases over the past 50 years.

July 12th is the bicentennial of the birth of Henry David Thoreau. The Concord Museum has even more cause to celebrate because a previously unknown daguerreotype of Sophia Thoreau has come to light and has been donated to the museum. It was bequeathed to the Concord Museum by the Geneva Frost Estate in Maine. Curator David Wood and collection’s manager Tricia Gilrein went to Maine and retrieve the rare image.

July 12th is the bicentennial of the birth of Henry David Thoreau. The Concord Museum has even more cause to celebrate because a previously unknown daguerreotype of Sophia Thoreau has come to light and has been donated to the museum. It was bequeathed to the Concord Museum by the Geneva Frost Estate in Maine. Curator David Wood and collection’s manager Tricia Gilrein went to Maine and retrieve the rare image.

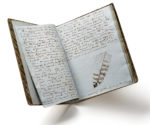

The daguerreotype of Sophia will go on display at the Concord Museum in This Ever New Self: Thoreau and His Journal, the first major exhibition dedicated to Henry David Thoreau, which opens in Concord on September 29th, 2017. The exhibition is currently at the Morgan Library & Museum, collaborators with the Concord Museum on this very  special show. Thoreau journaled his entire adult life, recording his thoughts, observations of his surroundings, books he’d read, and botanical data from Walden that scientists are still studying today. When the exhibition opens in Concord, the new image of Sophia will be displayed next to her brother’s quill pen, one of the many artifacts that she preserved for posterity. It still bears a tag with labelled in Sophia’s own hand: “The pen that brother Henry last wrote with.”

special show. Thoreau journaled his entire adult life, recording his thoughts, observations of his surroundings, books he’d read, and botanical data from Walden that scientists are still studying today. When the exhibition opens in Concord, the new image of Sophia will be displayed next to her brother’s quill pen, one of the many artifacts that she preserved for posterity. It still bears a tag with labelled in Sophia’s own hand: “The pen that brother Henry last wrote with.”