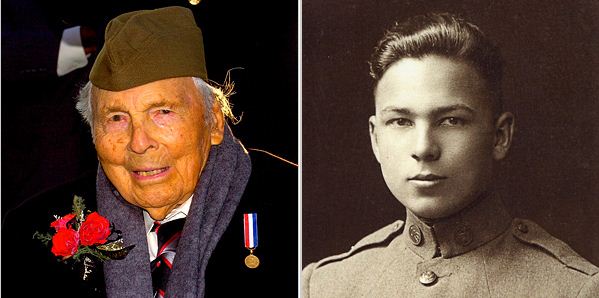

Frank Woodruff Buckles lied about his age and joined the Army in August of 1917 when he was 16 years old. Since he was anxious to see action, he volunteered to drive ambulances, a duty that he had heard would get him to the Western front the fastest. He was deployed in December of that year, sailing to England on the Carpathia, the ship that rescued the survivors of the Titanic, then going on to various places in France.

“The little French children were hungry,” Mr. Buckles recalled in a 2001 interview for the Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress. “We’d feed the children. To me, that was a pretty sad sight.”

Mr. Buckles escorted German prisoners of war back to their homeland after the Armistice, then returned to America and later worked in the Toronto office of the White Star shipping line.

He traveled widely over the years, working for steamship companies, and he was on business in Manila when the Japanese occupied it following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. He was imprisoned by the Japanese, losing more than 50 pounds, before being liberated by an American airborne unit in February 1945.

He worked for a steamship until he retired in the mid-1950s, then he ran a cattle farm for another 50 or so years. As one of very few remaining World War I veterans, Buckles was a frequent participant in parades and national memorial events during the past decade. He was extensively interviewed, relaying his unique memories of the Great War. For instance, he told an interviewer how he had seen veterans of the Crimean War in a ceremony in England. That’s the Charge of the Light Brigade war, from the 1850s. One 110-year-old man connected us to so much history that seems so distant when we read about it.

He passed away on Sunday at his home in Charles Town, West Virginia. In 2007, he was one of four U.S. World War I veterans still alive, two of whom served Stateside and one with Canadian forces in Britain, so even then Buckles was the only surviving veteran of the Western front. As of February 2010, he was the last US World War I veteran alive and only one of three people remaining in the world who had served in the war in any capacity.

Now there are only two: Claude Choules, of the British Royal Navy, now living in Australia, and awesomely, Florence Green, of the British Women’s Royal Air Force, now living in England. Florence joined the Women’s Royal Air Force right at the end of the war, in September 1918, when she was 17. She worked in the mess halls of two Norfolk airbases. Choules saw much action from 1916 onwards, serving on the HMS Revenge, and witnessing the scuttling of the German fleet at Scapa Flow, Scotland, on June 21, 1919.

The Veterans’ History Project and the Library of Congress have an exceptional series of interviews with Frank Buckles, plus documents and pictures from his collection online. It’s not to be missed, seriously. Then when you’re done being fascinated by Frank, check out the rest of the VHP’s World War I archive.

RIP MR. Buckles.

I’ve never really seen the Crimean War as being that far removed. I suppose that’s because of the political connections to the World Wars and how they ultimately lead to the Cold War. The Crimean War marked the beginning of the Anglo French alliance. Prior to this they had been bitter enemies for centuries. The actual alliance of course wasn’t continuous to the time of WWI, but it was still a big sea change in the relationship between the two countries. The First World War of course led to the Second which led to the Cold War, which was still going on in my youth and teens, making it seem more ‘current’ to me. I’m probably not explaining myself very well, suffice to say that seeing the connections makes it seem more modern.

Well, there probably aren’t many European wars that didn’t have a number of strong roots in previous European wars. At the very least that line goes back to the French Revolution. Still, it seems to me the 20th century wars are more of a physical presence with the 21st century we’re in still so fresh and new.

:skull:

Apart from all the normal risks in life, Mr Buckles was supremely fortunate three times (as an ambulance driver in WW1, on the Carpathia and in the Japanese prisoner of war camp in WW2. I am delighted he was extensively interviewed, since most generals wouldn’t have the remotest clue what real battle conditions were like.

True that, and I just edited in a paragraph at the end of the entry to link to some of the online interviews. He was a fascinating, vibrant man who lived a lot of life.

I have been researching and trying to find out why they called him doughboy and I can’t seem to find that answer. He stood what for what America’s Veterans are all about.

There are many different theories for how the term came about. It seems to have begun being used to describe infantry in the Mexican-American War back in the 1840s. It could have been a reference to them being dust-covered, or to a clay they used to polish brash.

It’s incredibly sad to think of all the knowledge and experience that goes with every sad passing of a WWI veteran. Harry Patch, the British vet who died in 2009 was an excellent example. It’s as though through their memories they have access to a world that will never be witnessed again. It must be quite a burden to be one of the few men or women left on this planet able to tell such a story, and very brave of Buckles to (as it says on the VHP site you link to) talk about his experiences, to get them out of his system. We need to do everything we can do preserve these memories for ourselves and for future generations.

I agree entirely. We’re extremely fortunate that Mr. Buckles lived so long that for the last decade he was very much in demand for interviews.

“Doughboy” was used in the Mexican-American war, but had no real connection to the usage of the term during the Great War.

The British came up with the term for American troops coming to join their ranks late in the war. The new American troops were extremely fresh, and very green. Whereas, the British, French, and German troops were battle-hardened.

Hence the term: “Doughboy.”