A 34-year-old car salesman who had just decided to try his hand at treasure hunting went into this store in Berkhamstead, Hertfordshire and purchased a $150 entry-level metal detector advertised as ideal for children and beginners. A few weeks later, he came back to the store with 55 Roman gold coins he had found on private land north of St. Albans and asked the staff what he should do with them. Store owner David Sewell, who has spent years metal detecting (and his best score was a rare medieval silver penny), told the lucky bastard to contact the local Portable Antiquities Scheme Finds Liaison Officer.

In early October, local officials, the finder and the guys from the store, armed with more powerful metal detectors, joined up for a second, more extensive investigation of the field.  In the 15 yards of woodland they explored, they unearthed another 104 gold coins, bringing the total up to 159.

In the 15 yards of woodland they explored, they unearthed another 104 gold coins, bringing the total up to 159.

All of them are 22-carat gold solidus coins struck in Milan (capital of the Western Empire from 286 A.D. to 402 A.D) and Ravenna (capital of the Western Empire from 402 A.D. until the collapse in 476 A.D.) in the late 4th century. The solidi bear the names and faces of the five different emperors who issued them: Gratian, Valentinian, Theodosius, Arcadius and Honorius, the last Roman emperor to rule Britain. They are in incredible condition. When I first saw a thumbnail of the find, I thought they were double eagles or some other relatively recent gold minting. The high resolution picture confirms that they look as fresh as the day they were struck. Be sure to click on the picture to see them in all their impeccable glory.

Their condition is particularly impressive considering that they’ve almost certainly encountered the business end of farming equipment. The woodland where the coins were discovered has been quarried and farmed over the past two centuries, which is probably why the coins were found scattered over the area instead of together in a container. Given how immensely valuable solidi were, particularly in the waning days of Roman Britain when very little new currency was sent up north from Italy, they must have been buried in a container rather than just wrapped in an organic textile. No remains of a vessel were found.

Solidi were not circulation coins. Here’s David Thorold, Prehistory to Medieval Curator at Verulamium Museum, on the subject:

“Gold solidi were extremely valuable coins and were not traded or exchanged on a regular basis. They would have been used for large transactions such as buying land or goods by the shipload.

“The gold coins in the economy guaranteed the value of all the silver and especially the bronze coins in circulation. If you saved enough bronze, you could exchange it for a silver coin. If you saved enough silver, you could exchange it for a gold coin. However, most people would not have had regular access to them. Typically, the wealthy Roman elite, merchants or soldiers receiving bulk pay were the recipients.”

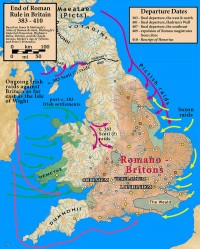

Hoards were buried either as a sacrifice to the gods or to keep valuables safe during dangerous times. I’m guessing the latter is the case here, since they were buried at a time when Roman troops were withdrawing from Britain and Saxon raiders were making mincemeat of southeastern England.

Hoards were buried either as a sacrifice to the gods or to keep valuables safe during dangerous times. I’m guessing the latter is the case here, since they were buried at a time when Roman troops were withdrawing from Britain and Saxon raiders were making mincemeat of southeastern England.

What is now St. Albans was known in Roman times as Verulamium. It was granted the rights of a Roman city in 50 A.D., extremely early in the history of Roman Britain, and became a large, prosperous market city on a major Roman road. At its height, it was the third largest town after Londinium (London) and Corinium (Cirencester). The city was already in decline by the second half of the 4th century, its once-beautiful theater, one of the few in Britain, used as a  garbage dump. After Honorius withdrew the last Roman garrisons in 410 A.D., the city of Verulamium was abandoned. Its remains were used as a quarry in the Middle Ages by the nearby town of St. Albans which eventually expanded to include the area of the old Roman city.

garbage dump. After Honorius withdrew the last Roman garrisons in 410 A.D., the city of Verulamium was abandoned. Its remains were used as a quarry in the Middle Ages by the nearby town of St. Albans which eventually expanded to include the area of the old Roman city.

This is one of the largest collections of solidi ever found. (The largest was the Hoxne Hoard, which included 569 solidus coins among many other treasures.) It’s certainly a discovery of national significance, and the local museum, the Verulamium Museum, is very keen to acquire them for display. Before that can happen, the coins have to be assessed by experts at the British Museum and then declared treasure at a coroner’s inquest. The local museum will then be given the opportunity to purchase the treasure at the assessed value, with all proceeds split between the finder and the landowner.

Amazing when you imagine the string of events that would have to happen before someone finds something like that.

Seriously, and with not a single scratch on them. The odds of such a find make winning the lottery look like heads or tails.

Those are some pretty awesome-looking coins.

Downright dreamy. :yes:

Fascinating! Such a rare find, by an amateur! Who would have thought???

Before that can happen, the coins have to be assessed by experts at the British Museum and then declared treasure at a coroner’s inquest.

Coroner’s inquest? They do thing differently in the U.K. than in the U. S., don’t they?

They sure do. According to the terms of the 1996 Treasure Act, all potential treasure objects (anything made out of gold or silver that is at least 300 years old, any coin or object that is part of a larger find, anything prehistoric) must be declared by the finder to the Coroner. The Finds Liaison Officer will give it a preliminary examination to see if it qualifies as treasure. If it doesn’t, it gets returned to the finder without an inquest.

If it does, the Coroner holds an inquest at which experts testify as to whether the object is as defined in the Treasure Act. If it is declared treasure, it automatically becomes property of the Crown and is taken to the British Museum where a Treasure Valuation Committee determines market value. If a local museum wants to buy the object, they raise the amount assessed by the Valuation Committee which will then be given to the finder and landowner as a sort of finder’s fee to encourage reporting. If no museum wishes to acquire it, the Secretary of State disclaims it and ownership reverts to the finder.

The system has had its successes and its failures, the Crosby Garret helmet is a prime example of the latter.

And then there are such dramatic events involved as well: a huge amount of quite portable wealth getting buried, all coined before the end of Roman rule. You cannot help but think that whatever they were afraid of must have happened, as no-one seems to have been in a position to go and retrieve it afterwards.

I bet they all died. :skull:

I see. Coroner’s inquests on this side are always connected with deaths, suspicious deaths in particular. Coroners have largely been replaced by Medical Examiners. Shows like CSI* have become very popular. (*Crime Scene Investigation)

Here is an article I found in Wikipedia. Scroll down to “Federal Law” under “United States” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treasure_trove

In the States, each state in the U.S. has its own laws regarding found property less than 100 years old, but the federal government has jurisdiction over artifacts over 100 years old.

There are still plenty of coroners in the US. Sadly most of them are elected and local laws don’t even require that they be doctors. Frontline and Nova on PBS have had some terrifying and illuminating episodes dedicated to the disastrous system of death investigation in the US. There’s no oversight, no federal standard and mistakes and fraud abound. Unfortunately CSI is fiction in every possible way.

Coroners in the UK still do death investigations. That’s their main job. I think they were enlisted by the Treasure Act to do the treasure findings simply because they had a public inquest process good to go.

Some body found one of liv”s issues…

:shifty:

I am absolutely green with envy.

I had that one coin….