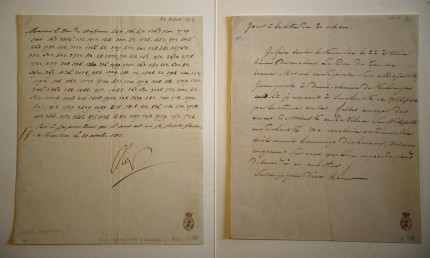

A letter written in a numerical code on October 20, 1812, detailing Napoleon’s plan to blow up the Kremlin on his retreat from Russia was purchased at auction on Sunday by the Museum of Letters and Manuscripts in Paris. The coded letter was sold along with its original transcription made in Paris three or four days later, a very rare pairing and a fortunate one since without the period transcription it’s unlikely we’d know the major historical significance of the letter’s contents. Perhaps spurred on by the bids of Russian plutocrats, the lot sold for €187,500 ($243,500), more ten times its pre-sale estimate of €15,000 ($19,500). It’s impressive that a museum won in the end.

Sent from Napoleon to Hugues-Bernard Maret, the Minister of Foreign Affairs (who would later be appointed Prime Minister of France under King Louis Philippe I for exactly eight days in November 1834) who was then in Vilnius, the letter baldly states “Je fais sauter le Kremlin le 22 à trois heures du matin” (“I am going to have the Kremlin blown up at three o’clock in the morning on the 22nd”). The letter then goes on to detail the route of his retreat and orders with unusually emotive urgency that more horses be sent to meet him at Smolensk: “Ma cavalerie est démontée et il meurt beaucoup de chevaux; ordonnez et prenez sur vous que l’on ne perde pas de temps à en acheter” (“My cavalry is in pieces and many horses are dying; order and ensure yourself that no time is wasted in purchasing [more horses]”). The letter is signed with a simple “Nap.”

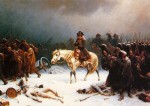

After a tactical victory at the bloody Battle of Borodino on September 7th, 1812, Napoleon’s path to Moscow was unobstructed. He entered the city on September 14th expecting to find the city leaders greeting him at the door with a key to the city. That was the way things usually worked when an invading army reached an undefended city, but instead he found Moscow evacuated and stripped of supplies. His desperate soldiers and animals would not be housed and fed by a cowed population. They would have to fend for themselves as they’d had to do since their supply lines became hopelessly stretched and their attempts to live off the land thwarted by the impossible logistics of an eastward invasion of Russia’s wide-open sparsely populated and thinly cultivated spaces.

Napoleon had expected Tsar Alexander I to surrender when Moscow fell to the French, but the Russians just regrouped and waited him out. Frustrated that his victories on the field had won his Grande Armée little but huge casualty rates, starvation, frostbite, typhus and mass desertion, Napoleon finally left Moscow on October 19th, the day before he sent the coded letter. He left the city in the hands of Marshal Edouard Mortier, Duke of Treviso. It was Mortier who would follow Napoleon’s orders to blow up the Kremlin. He packed the entire complex with explosives and set them off, but yet again Mother Russia’s Mother Nature interfered with French plans. Rain fell, soaking the fuses and impeding the full destruction of the Kremlin. The arsenal, the wall and a number of towers were destroyed by explosions. Subsequent fires damaged the 15th century Palace of the Facets and several of the churches.

Napoleon had expected Tsar Alexander I to surrender when Moscow fell to the French, but the Russians just regrouped and waited him out. Frustrated that his victories on the field had won his Grande Armée little but huge casualty rates, starvation, frostbite, typhus and mass desertion, Napoleon finally left Moscow on October 19th, the day before he sent the coded letter. He left the city in the hands of Marshal Edouard Mortier, Duke of Treviso. It was Mortier who would follow Napoleon’s orders to blow up the Kremlin. He packed the entire complex with explosives and set them off, but yet again Mother Russia’s Mother Nature interfered with French plans. Rain fell, soaking the fuses and impeding the full destruction of the Kremlin. The arsenal, the wall and a number of towers were destroyed by explosions. Subsequent fires damaged the 15th century Palace of the Facets and several of the churches.

Most of the complex was restored over the next 20 years, although some parts, like the Vodovzvodnaya Tower, were either completely destroyed or so damaged they had to be demolished. The Kremlin Arsenal was restored in neoclassical style and turned into a museum celebrating Russia’s great victory over Napoleon. The walls of the arsenal are decorated with 875 cannons captured by the Grande Armée during its disastrous retreat.

Until the end Napoleon insisted that the Russians had never defeated him militarily, that it was solely the Russian winter than could claim victory over him. He reiterates that point, rebutting critics who blamed his failures of supply logistics and planning, in another document that was sold at the same auction of Sunday. Essay on Countryside Fortification is a 310-page manuscript dictated by Napoleon to his faithful aide-de-camp Grand Marshal Betrand and his secretary Louis Marchand while he was in exile on the island of Saint Helena. Written in 1818-19, the illustrated manuscript details Napoleon’s thoughts on fortifications and the art of war in general. It includes a chapter in which he defends the Russian campaign, saying “Elle ne doit pas s’appeler une retraite puisque l’armée était victorieuse” (“It shouldn’t be called a retreat since the army was victorious”).

Until the end Napoleon insisted that the Russians had never defeated him militarily, that it was solely the Russian winter than could claim victory over him. He reiterates that point, rebutting critics who blamed his failures of supply logistics and planning, in another document that was sold at the same auction of Sunday. Essay on Countryside Fortification is a 310-page manuscript dictated by Napoleon to his faithful aide-de-camp Grand Marshal Betrand and his secretary Louis Marchand while he was in exile on the island of Saint Helena. Written in 1818-19, the illustrated manuscript details Napoleon’s thoughts on fortifications and the art of war in general. It includes a chapter in which he defends the Russian campaign, saying “Elle ne doit pas s’appeler une retraite puisque l’armée était victorieuse” (“It shouldn’t be called a retreat since the army was victorious”).

The museum paid €375,000 euros ($490,000) for Essay on Countryside Fortification which was the last of Napoleon’s manuscripts still in private hands. That means they dropped three quarters of a million dollars on two documents, bless their hearts. For a museum founded only eight years ago not by some philanthropic Getty-style billionaire but by Gerard Lhéritier, owner of a company that buys and sells historic letters and documents, it is remarkably well-endowed. The newest acquisitions will doubtless make outstanding additions to the Museum of Letters and Manuscripts’ Napoleon I exhibit.

“It shouldn’t be called a retreat since the army was victorious” (said Napoleon of the not-a-retreat from Moscow) – sort of leaves you wondering what it SHOULD be called.

What it SHOULD be called ? Without some sort of ‘commonwealth’ such ventures are seemingly nothing but a lousy Ponzi-scheme and are in most of the cases bound to starve since the days of Alexander. Remains of his “undefeated” army, if I remeber correctly, have recently been unearthed in the Baltic – I think there was a post on this. Once again, ‘Publicity’ is key: Just to give an idea about his auxiliaries:

”From the 30.000 men of the 6th Bavarian Corps a meager 68 were combat-ready by December 13th. Of more than 27.000 Westphalen troopers, only 800 were able to return. After the withdrawal, of 15.800 Wurttembergers still 387 men were present. The Baden Division, starting off with about 7.000 men, was on 30 December 30th composed of 40 combat-capable soldiers and 100 sick ones. The Saxon cavalry brigade ‘Thielmann’ was almost completely destroyed at Borodino and 55 men came back. Out of 2.000 Mecklenburgers 59 returned. Only the two auxiliary corps of Austria and Prussia, who have never went far into Russian territory and therefore had shorter supply and exit routes, have lower casualty figures” (an edited Gxxgle translation).

And a different (russian) story: “Davidov and other Russian campaign participants record wholesale surrenders of starving members of the Grande Armée well before the onset of frosts amid eyewitness reports of cannibalism and point to the breakdown in French supply and constant harassment of the French army by Russian forces as the primary reasons for their losses during the retreat.”

Although it wasn’t in Asia, “Classic Military Blunder,” comes to mind.