The mummy was donated to the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, Croatia, by Archbishop Juraj Haulik, a Croatian nationalist and the first archbishop of Zagreb, in the 19th century. In 2008, museum researchers took the mummy to Zagreb’s University Hospital Dubrava for further study. Using X-rays, CT scans and radiocarbon dating, they determined the mummy was a woman who died 2,400 years ago from causes unknown at the age of 40. She had a healed fracture in one of her hands.

The mummy was donated to the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb, Croatia, by Archbishop Juraj Haulik, a Croatian nationalist and the first archbishop of Zagreb, in the 19th century. In 2008, museum researchers took the mummy to Zagreb’s University Hospital Dubrava for further study. Using X-rays, CT scans and radiocarbon dating, they determined the mummy was a woman who died 2,400 years ago from causes unknown at the age of 40. She had a healed fracture in one of her hands.

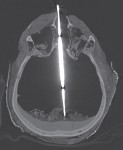

She also had a tubular object stuck between her left parietal bone and the resin material filling the space in front of her occipital bone. Researchers could see the thing on a CT scan but were unable to identify it. Attenuation values (a measurement of how much light can get through a given material) suggested that it was an artificial object rather than a body part, but previous studies had found similar structures that turned out to be remains of the dura mater that had hardened during the mummification process. Only removing the object would allow them to determine exactly what it was.

She also had a tubular object stuck between her left parietal bone and the resin material filling the space in front of her occipital bone. Researchers could see the thing on a CT scan but were unable to identify it. Attenuation values (a measurement of how much light can get through a given material) suggested that it was an artificial object rather than a body part, but previous studies had found similar structures that turned out to be remains of the dura mater that had hardened during the mummification process. Only removing the object would allow them to determine exactly what it was.

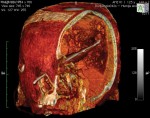

In order to do this in the least invasive way possible if possible, researchers employed a combination of endoscopy and CT monitoring, an innovative approach that as far as they know has never been utilized before. They cut a small incision in the skin of the nose to access a hole in the ethmoid bone (the bone that separates the nasal cavity from the brain) that the embalmers had created when the removed the brain 2,400 years ago.

In order to do this in the least invasive way possible if possible, researchers employed a combination of endoscopy and CT monitoring, an innovative approach that as far as they know has never been utilized before. They cut a small incision in the skin of the nose to access a hole in the ethmoid bone (the bone that separates the nasal cavity from the brain) that the embalmers had created when the removed the brain 2,400 years ago.

The endoscope was at the wrong angle in their first attempt, but that’s where the CT monitoring came in handy. They were able to correct the angle and insert the rigid endoscope through the hole into the cranial cavity. Once they saw that they were properly positioned at the base of the mystery object, researchers threaded a clamp through the endoscope and detached the tube from the resin.

The endoscope was at the wrong angle in their first attempt, but that’s where the CT monitoring came in handy. They were able to correct the angle and insert the rigid endoscope through the hole into the cranial cavity. Once they saw that they were properly positioned at the base of the mystery object, researchers threaded a clamp through the endoscope and detached the tube from the resin.

When they pulled it out, the found the object was a fragment of what looked like wood about 3 inches long. Although the material was too brittle to make a microscopic slide, botanists were able to examine the end of it under a stereo microscope and found that it’s not actually wood, but rather a stem fragment from a plant in the monocotyledon group, one of two major groups of flowering plants that includes everything from orchids to palms to grasses to palms to grains to bamboo. This stick probably came from the family Poaceae, which includes cane and bamboo.

monocotyledon group, one of two major groups of flowering plants that includes everything from orchids to palms to grasses to palms to grains to bamboo. This stick probably came from the family Poaceae, which includes cane and bamboo.

This study has not only revealed how useful the combination of endoscopy and CT scanning can be in minimizing damage to archaeological remains, but it also adds intriguingly to our knowledge of Egyptian mummification practices. There are few contemporary descriptions of mummification procedures. Herodotus describes three approaches to embalming in the second book of his Histories, and only the most expensive of these involves transnasal excerebration (ie, the removal of the brain through the nose): “First with a crooked iron tool they draw out the brain through the nostrils, extracting it partly thus and partly by pouring in drugs.”

Perhaps the iron hooks were used during a specific period of time or, as Herodotus suggests, for the elite, while cheaper materials like wooden sticks and canes were used in less expensive treatments. Experiments in the 60s confirmed that it was possible to remove the brain using metal tools inserted through the nostrils, either by repeatedly driving the tool into the skull and removing the brain matter that would stick to it, or by twisting the tool in a circular motion to liquefy the brain and then turning the corpse over to allow the liquified brain to drip out the nose.

There are no descriptions of sticks being used for this purpose, however, and it seems like it would be a lot harder to pierce the ethmoid and extract brain with wood or cane than it would be with iron. It can be done, though. Experiments on cadavers in the early 1990s proved that a bamboo rod wrapped in moistened linen bandages could indeed remove the brain through the nose. Now we’ve found an actual bamboo or cane rod in the actual brain cavity of a mummy, an important confirmation that what 20-year-old experiments have proven might have been done was in fact done.

I would have thought that using a straw would be easier.