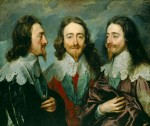

Anthony Van Dyck painted many portraits of doomed King Charles I and his courtiers. The most famous among them is probably Charles I in Three Positions, a triple portrait that shows the king face-on, in full left profile and in three-quarters right profile.

Anthony Van Dyck painted many portraits of doomed King Charles I and his courtiers. The most famous among them is probably Charles I in Three Positions, a triple portrait that shows the king face-on, in full left profile and in three-quarters right profile.

Now one of the gems in the Royal Collection, the portrait was originally a work piece sent to the sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini in Rome. He had been commissioned by Pope Urban VIII to make a bust of King Charles which the pope would then present as a gift to the Catholic Queen Henrietta. Since the king was not able to sit for Bernini in person, he commissioned his favorite painter, Van Dyck, to make a portrait showing him from several angles which could be used as a schematic by the sculptor. He sports a different silk outfit in each to give Bernini textural options and there’s a tear-drop pearl earring that would make Vermeer salivate in the three-quarters profile, but in all three looks he wears similar delicate lace overlay collars and the blue ribbon of the Order of the Garter.

Bernini, never one to mince words, royalty or no royalty, is said to have remarked upon examination of the triple portrait: “Never have I beheld features more unfortunate.” It seems premonitory in hindsight given just how unfortunate Charles’ ending was, but he probably just meant that all of Van Dyck’s Baroque flourishes and all the lace and silk in King Charles’ closet couldn’t make him look like any less of a sad sack, which, I think we can all agree, is a pretty fair assessment.

Still, Bernini managed to enhance Charles’ qualities enough that the bust, finished in the summer of 1636 and presented to their majesties in July 1637, was a huge hit with King and Queen. It didn’t push the sovereign over the edge to Catholicism as the Pope had hoped it would, but it at least curried favor. The court roundly agreed that it was a most excellent likeness exquisitely executed, if you’ll pardon the term. Charles gave Bernini an expensive diamond ring to reward him for his work. Sadly, the bust was almost as short-lived as the king. It was destroyed by a fire in Whitehall Palace in 1698.

There’s a portrait bust of King Charles I from the early 18th century in the Royal Collection which some believe to be a copy of Bernini’s piece, but there’s no evidence the sculptor ever saw the original before it was lost. The king is wearing something that looks like the three-quarters profile outfit with that big puff of bunched diagonal silk, but the lace collar is much smaller and more twee, and the king’s jaw line bears no relation to the original. He is wearing his Order of the Garter medallion and ribbon, though.

There’s a portrait bust of King Charles I from the early 18th century in the Royal Collection which some believe to be a copy of Bernini’s piece, but there’s no evidence the sculptor ever saw the original before it was lost. The king is wearing something that looks like the three-quarters profile outfit with that big puff of bunched diagonal silk, but the lace collar is much smaller and more twee, and the king’s jaw line bears no relation to the original. He is wearing his Order of the Garter medallion and ribbon, though.

As for the Van Dyck painting, Bernini kept it. It passed to his heirs after his death and remained in the Bernini Palace on the Via Del Corso until it was bought by an agent of British art dealer William Buchanan in 1802. After passing through the hands of two private collectors, it was purchased for the Royal Collection by King George IV in 1822.

But what happened to the King Charles I’s Order of the Garter ribbon? He may have brought it with him to the scaffold. We know he gave one of the George badges that are part of the Order’s regalia to William Juxon, the Bishop of London, just before he was beheaded, but Parliament confiscated and sold everything of Charles’ they could get their hands on to creditors who immediately resold whatever they got, so ownership histories have gotten very muddled. Besides, a blue ribbon, as fond as the king was of it, can’t have been seen as a high ticket item, and as a textile is far easier to destroy than to preserve.

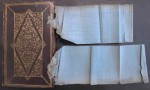

However in 1949, a viable candidate actually surfaced. Queen Mary, grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II, was given a first edition of Eikon Basilike: The Portraicture of His Sacred Majestie in His Solitudes and Sufferings. This book was published in 1649 just 10 days after King Charles’ execution and is purportedly musings written by the king himself on his reign, the hardships he endured, his enemies, his faith. There’s long been a debate as to the authorship, but there is evidence that he wrote at least parts of it, or that it was derived from his personal papers.

However in 1949, a viable candidate actually surfaced. Queen Mary, grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II, was given a first edition of Eikon Basilike: The Portraicture of His Sacred Majestie in His Solitudes and Sufferings. This book was published in 1649 just 10 days after King Charles’ execution and is purportedly musings written by the king himself on his reign, the hardships he endured, his enemies, his faith. There’s long been a debate as to the authorship, but there is evidence that he wrote at least parts of it, or that it was derived from his personal papers.

The copy given to Queen Mary had four lengths of blue silk ribbon attached to the binding.  An inscription at the front of the book claimed that these were the remains of King Charles’ Order of the Garter sash.

An inscription at the front of the book claimed that these were the remains of King Charles’ Order of the Garter sash.

“The Book was the gift of Sir Oliver Flemming Master of the Ceremonies to King Charles the First, together with ye ribband strings which were the Garter His Majesty wore his George on.”

Nobody was going to take the inscription’s word for it, though. Even if it were a Garter ribbon, it could be anybody’s from any time.

The Eikon Basilike is now kept in the royal library at Windsor Castle. When Royal Collection Trust curators selected the Van Dyck triple portrait for display in an upcoming exhibit called In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion, they decided to take a closer look at the ribbons in the book on the off chance that they might actually be the one depicted in the painting.

The Eikon Basilike is now kept in the royal library at Windsor Castle. When Royal Collection Trust curators selected the Van Dyck triple portrait for display in an upcoming exhibit called In Fine Style: The Art of Tudor and Stuart Fashion, they decided to take a closer look at the ribbons in the book on the off chance that they might actually be the one depicted in the painting.

They radiocarbon dated a piece of the ribbon and found that it dates to between 1631 and 1670. Charles reigned from 1625 until 1649, and he sat for that Van Dyck portrait in 1635-6. It’s also the proper width and length for a Garter sash, 10 centimeters (four inches) wide and 136 centimeters (53.5 inches) long.

They radiocarbon dated a piece of the ribbon and found that it dates to between 1631 and 1670. Charles reigned from 1625 until 1649, and he sat for that Van Dyck portrait in 1635-6. It’s also the proper width and length for a Garter sash, 10 centimeters (four inches) wide and 136 centimeters (53.5 inches) long.

So we still don’t know for sure that it’s King Charles I’s Order of the Garter sash — the wording of the inscription appears to be from the 18th century — but we now know that it certainly could be. The book and ribbons will be going on display along with the painting. A lace collar that dates to around 1636 that is believed to have belonged to Charles will join them to truly bring the painting to life.

“…. given to Queen Mary”?

Yes, it was given to Queen Mary. Is there a typo I’m not seeing? :confused:

http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20110530062854AAffGoD

😆 Ahh, I see. The questioning emphasis is on the “given.” That’s hilarious. I suspect she was far from the only royal to enjoy kleptomania by coercion. I remember an anecdote told by an old friend of the family. She grew up in a wealthy family in pre-Revolutionary Egypt. When King Farouk came to visit their home, they whipped out this fancy set of china that had once belonged to Napoleon. The King mentioned in passing on his way out the door that he really liked that china, so they packed it up and gave it to him. It was just assumed that “I like it” meant “hand it over.”

There are various anecdotes of Queen Mary poking around the cupboards and drawers of houses she visited and, on occasion, of her annoyance when something she particularly wanted had been spirited away by her hosts in advance of her arrival.

There is a typo: “…that shoes the king face-on….” Unless you’re doing an Ed Sullivan joke.

I am not, but it’s an excellent excuse. Thank you. :thanks:

Great story, thank you.

Despite knowing this painting for years, there are two things I haven’t made a note of before.

1. That the three different silk outfits were there for a specific reason *sigh*.

2. That Bernini and his heirs kept the Van Dyck painting. Since it was purchased for the Royal Collection (by King George IV in 1822), I assume I thought it had always been in the royal collection *double sigh*.

This is an old story and has absolutely no basis in fact. I have spoken to several people who knew Queen Mary intimately, including my mother and grandmother, and not one person has ever heard of her demanding anything.

If I remember correctly, Edward VIII remarked after his mother Queen Mary’s death that, “I suppose it is possible that the blood in my mother’s veins is now colder than when I knew her.” If George V had managed to secure the hand of the later Queen Marie of Rumania, the history of the House of Windsor might have been quite different.

As for Queen Mary’s collecting habits, there is the story of her visiting a home where some item was that she wanted, a desire not unknown to her host, and sitting determinedly late into the evening until at last it was presented to her, whereupon she promptly took her leave!

This trio-of-portraits is a favorite. Long ago, (inspired by this artwork) I did a somewhat similar set of graphite portraits of a young man. The piece was extremely important to me. He assumed it was a gift and flippantly gave it to his Mother. He was extremely shallow, not recognizing how much of an artist’s heart goes into such portraits. This wonderful Van Dyck article is greatly appreciated.