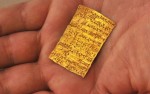

The fate of an ancient artifact looted from Berlin’s Vorderasiatisches Museum at the end of World War II is now in the hands of the New York Court of Appeals. In a twist from the way these stories usually go, this piece was taken out of Germany by Holocaust survivor Reuven Flamenbaum who, according to family lore, traded a Soviet soldier two packs of cigarettes or a salami for it after his liberation from Auschwitz. The Soviets helped themselves to the contents of German museums during the final days and weeks of the war and they weren’t alone. German troops did the same, as did penniless and desperate civilians some of whom had taken shelter from the bombing, shelling and advancing armies in the museum itself. A tablet of Assyrian gold the size of a very large stamp or very small credit card is a highly appealing form of currency in a black market economy.

Flamenbaum, originally from Poland, took it with him when he moved to the US in 1949, even using it as collateral to buy the liquor store on Canal Street where he worked. He took it to Christie’s in 1954 to have it appraised and they declared it a forgery worth no more than $100. According to his daughter Hannah, her father never wanted to sell it anyway. He kept the gold card, at various times on display on a mantel or in a red wallet, as a memento of his survival. She fondly recalls playing with the delicate 9.5-gram piece.

Flamenbaum, originally from Poland, took it with him when he moved to the US in 1949, even using it as collateral to buy the liquor store on Canal Street where he worked. He took it to Christie’s in 1954 to have it appraised and they declared it a forgery worth no more than $100. According to his daughter Hannah, her father never wanted to sell it anyway. He kept the gold card, at various times on display on a mantel or in a red wallet, as a memento of his survival. She fondly recalls playing with the delicate 9.5-gram piece.

Reuven Flamenbaum died in 2003 and Hannah was named executor of his estate. Three years later, Reuven’s son Israel Flamenbaum disputed Hannah’s accounting of the estate and notified the Vorderasiatisches Museum that its long-lost gold tablet was in a safety deposit box on Long Island. The museum immediately filed suit to reclaim the artifact, asserting they held legal title since it was legally acquired and illegally removed. The Flamenbaum estate countered citing the spoils of war doctrine which purportedly made anything looted by Soviet troops their legal property and thus legal to sell for two packs of smokes, and the doctrine of laches, a legal doctrine that requires an owner “exercise reasonable diligence to locate” lost property. Their contention was that since the museum hadn’t told the authorities the tablet was missing or listed it on a stolen art registry after the war and hadn’t actively searched for it in the six decades since, it had given up its ownership claim.

Assuming Christie’s was wrong and it’s the genuine article, the tablet was unearthed by an archaeological team from the German Oriental Society excavating the foundations of the Ishtar Temple, a ziggurat in the Assyrian city of Ashur in what is now northern Iraq but was then part of the Ottoman Empire. The temple was built by King Tukulti-Ninurta I (1243-1207 B.C.). The gold tablet was inscribed in cuneiform with a dedication calling on all who visit the temple to honor the king’s name.

After the end of excavations in 1914, the tablet was loaded on freighter in Basra headed for Germany. The untimely outbreak of World War I forced the ship to change course and head for Lisbon instead. The vast trove of artifacts — they found 16,000 cuneiform tablets alone — had to be stored in Portugal while war raged. Finally in 1926 the tablet arrived in Berlin. It was put on display in 1934 only to be forced into storage again by another world war. The museum put it in storage for its own protection in 1939. They don’t know when exactly it was removed, which is why they can’t say for certain who stole it, but it was discovered to be missing when inventory was taken after the war in 1945.

After the end of excavations in 1914, the tablet was loaded on freighter in Basra headed for Germany. The untimely outbreak of World War I forced the ship to change course and head for Lisbon instead. The vast trove of artifacts — they found 16,000 cuneiform tablets alone — had to be stored in Portugal while war raged. Finally in 1926 the tablet arrived in Berlin. It was put on display in 1934 only to be forced into storage again by another world war. The museum put it in storage for its own protection in 1939. They don’t know when exactly it was removed, which is why they can’t say for certain who stole it, but it was discovered to be missing when inventory was taken after the war in 1945.

The museum didn’t report the loss at the time because it was a drop in a very large bucket of pillaged antiquities and the divided authorities of post-war Berlin made for a chaotic legal environment. As for attempting to locate the tablet on its own, that would have been a needle-in-a-haystack job and the museum had so many missing needles in a world of haystacks.

In 2010, a Nassau County Surrogate’s Court found for the Flamenbaum estate, agreeing that museum had failed to make sufficient efforts to find the property as per the doctrine of laches. The Surrogate’s Court judge mistakenly believed that the museum knew from a tip received in 1954 that the tablet was in New York, but the museum denied knowing anything until it received Israel Flamenbaum’s letter in 2006. In 2012 the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court overturned the 2010 decision, agreeing with the museum that it held clear title and that laches didn’t apply because the Flamenbaum estate hadn’t demonstrated that the museum “failed to exercise reasonable diligence to locate the tablet and that such failure prejudiced the estate.” The court noted that even if the museum had reported the artifact stolen to the police and listed it a stolen art registry, there’s no reason to believe they would have found the piece as a result.

The seven judges of the New York Court of Appeals heard arguments in the case on Tuesday. Their decisions typically take four to six weeks, so within the next two months we should know whether the tablet will remain with the Flamenbaums or return to the Vorderasiatisches Museum. If the court finds in favor of the Flamenbaum estate, they want to donate the tablet to the Holocaust Museum in Washington.

I hoped to read about the history of the tablet itself, about its use and meaning, instead of its present (rightful??) owner. Pity 🙁

I did note that it was used as a religious dedication in the foundation of the Ishtar Temple, engraved with an appeal that all who worship there honor the king’s name.

Today’s happenings are tomorrow’s history. Lots of interesting things happening with that tablet today.

True that. I wonder what King Tukulti-Ninurta I would make of it all.

So, since Christie’s was apparently wrong, I wonder what the real dollar value would be.

I find that a bit odd, though. Even assuming it’s a forgery, isn’t it still gold? Wouldn’t a tablet of gold that size still be worth more than $100 even in 1954?

It really is very small. Gold went for $35.04 a troy ounce in 1954. The total weight of the tablet is 9.5 grams which converts to 0.3 troy ounces. That means on gold weight alone, it was worth less than $11, which raises the question of why it was deemed worth $100 if it was a fake. Sheer prettiness, perhaps? Cuneiform art.

Dang, 9.5 grams is a lot less than I imagined :confused:

That is some pretty sweet cuneiform, though 😀

Hell yeah. If I could do cuneiform like that on tiny tablets of gold, I would certainly mark up the price 10 times the gold value. At least.

One more thing: Was this ancient artifact “looted from Berlin’s Vorderasiatisches Museum at the end of World War I”, or was it in fact -at the end of “World War I”- Iooted from “Vorderasia” ?

However, the cuneiform itself clearly says that “Those among all the visitors of King Tukulti-Ninurta who currently are standing by so close that they are actually able to read this, are kindly asked to step back – Thank you !”.

:hattip:

Oh how I hate war numeral typos. :angry: Thank you!

What is Isreal Flamenbaum’s problem? Crying right away to the museum. It sounds

like he couldn’t get his way so Hannah couldn’t have it either. It probably would have looked nice in the D.C. Holocost museum.

I’m surprised that the museum didn’t find it more expedient to buy the piece back from the Flamenbaums rather than to sue them. Surely it would have been cheaper.

I bet if an ex Nazi were to find it, they would be forced to return the object, but if it’s a Jewish guy, nobody does anything. That’s racist. It isn’t there’s, and they should return it.

What do you mean nobody does anything? It’s a court case. Obviously somebody did something.

That’s horrible. If they are not looking for financial gain, it should be given back to rightful owner.