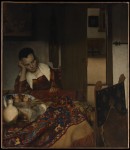

Saint Praxedis, an oil painting depicting the 2nd century saint cleaning the blood of a decapitated martyr, was first attributed to Johannes Vermeer in 1969. That year it had gone on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Florentine Baroque Art from American Collections as a work by Felice Ficherelli, aka Il Riposo. It was thought to be a second version of a nearly identical 1640-5 work by Ficherelli, but University of London art historian Michael Kitson proposed a very different hand was behind the copy. In his opinion, the signature “Meer 1655” on the bottom left of the painting “correspond[ed] exactly to those on Vermeer’s early works, particularly the Maid Asleep.” He also thought the treatment of the historical subject had elements in common with Vermeer’s Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, namely its “breadth of form and handling and a similar gravity (though not sickness) of mood.”

Saint Praxedis, an oil painting depicting the 2nd century saint cleaning the blood of a decapitated martyr, was first attributed to Johannes Vermeer in 1969. That year it had gone on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Florentine Baroque Art from American Collections as a work by Felice Ficherelli, aka Il Riposo. It was thought to be a second version of a nearly identical 1640-5 work by Ficherelli, but University of London art historian Michael Kitson proposed a very different hand was behind the copy. In his opinion, the signature “Meer 1655” on the bottom left of the painting “correspond[ed] exactly to those on Vermeer’s early works, particularly the Maid Asleep.” He also thought the treatment of the historical subject had elements in common with Vermeer’s Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, namely its “breadth of form and handling and a similar gravity (though not sickness) of mood.”

Kitson’s tentative attribution wasn’t widely accepted. Saint Praxedis was an unusual subject in Dutch painting in general and for Vermeer in particular, even though he did start out treating historical scenes like Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and Diana and her Companions, both of which were painted during Vermeer’s earliest productive years (1654-1656). Also, this would be the sole example of Vermeer copying the work of an Italian master, or anybody else for that matter.

Kitson’s tentative attribution wasn’t widely accepted. Saint Praxedis was an unusual subject in Dutch painting in general and for Vermeer in particular, even though he did start out treating historical scenes like Christ in the House of Martha and Mary and Diana and her Companions, both of which were painted during Vermeer’s earliest productive years (1654-1656). Also, this would be the sole example of Vermeer copying the work of an Italian master, or anybody else for that matter.

In 1986, Arthur Wheelock Jr., the influential curator of Northern Baroque painting at Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art, boosted Saint Praxedis‘s fortunes. Wheelock agreed with Kitson that there were stylistic similarities between Saint Praxedis and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary. He also suggested that the painting of the saint’s face was characteristically Dutch in modeling, comparable in its downcast posture to the young woman in A Maid Asleep. Wheelock noted a second potential signature on the right side. It’s barely distinguishable, but Wheelock posited that it said “Meer N R o o,” originally “[Ver]Meer N[aar] R[ip]o[s]o” or “Vermeer after Riposo.”

In 1986, Arthur Wheelock Jr., the influential curator of Northern Baroque painting at Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art, boosted Saint Praxedis‘s fortunes. Wheelock agreed with Kitson that there were stylistic similarities between Saint Praxedis and Christ in the House of Martha and Mary. He also suggested that the painting of the saint’s face was characteristically Dutch in modeling, comparable in its downcast posture to the young woman in A Maid Asleep. Wheelock noted a second potential signature on the right side. It’s barely distinguishable, but Wheelock posited that it said “Meer N R o o,” originally “[Ver]Meer N[aar] R[ip]o[s]o” or “Vermeer after Riposo.”

Wheelock’s arguments were controversial. Several important art historians and experts in Dutch painting thought the brushwork, lighting and quality had little in common with Vermeer’s known works. One of them couldn’t even find the so-called second signature, and even if he had, he wouldn’t have found it persuasive since it’s the only example of a signature shouting out the original artist. Many experts were convinced Saint Praxedis was of Florentine origin, painted by a student of Ficherelli’s, and that the signature was a later addition referencing an artist named Meer or van der Meer.

The painting was purchased the year after Wheelock’s first publication by Polish-American art collector Barbara Piasecka Johnson. She died last year, and works from the fine collection she and her husband Johnson & Johnson co-founder John Seward Johnson I put together will be going up for auction at Christie’s London on July 8th (view the catalogue here). With a potential pre-sale estimate of $11,000,000-$13,000,000 if she could be shown conclusively to have been painted by Vermeer’s hand, Christie’s enlisted experts from the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam’s Free University to test Saint Praxedis.

The painting was purchased the year after Wheelock’s first publication by Polish-American art collector Barbara Piasecka Johnson. She died last year, and works from the fine collection she and her husband Johnson & Johnson co-founder John Seward Johnson I put together will be going up for auction at Christie’s London on July 8th (view the catalogue here). With a potential pre-sale estimate of $11,000,000-$13,000,000 if she could be shown conclusively to have been painted by Vermeer’s hand, Christie’s enlisted experts from the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam’s Free University to test Saint Praxedis.

The results are pretty spectacular. From the Christie’s catalogue:

Particles of lead taken from samples of lead white pigment used in Saint Praxedis were submitted for high precision lead isotope ratio analysis at the Free University, Amsterdam. The results placed the lead white squarely in the Dutch/Flemish cluster of samples, establishing with certainty that its origin is north European and entirely consistent with mid-seventeenth century painting in Holland. Two separate samples from the picture have been tested to certify this result. This provides incontrovertible scientific proof that the picture was not painted in Italy. Furthermore, a lead white sample taken from Diana and her Companions was tested in the same manner to allow for comparison between Saint Praxedis and a work from the same approximate date that is universally accepted as by Vermeer. The outcome of this was extraordinary, providing an almost identical match of isotope abundance values between the two samples. They relate so precisely as to even suggest that the exact same batch of paint could have been used for both pictures.

As for why Vermeer would copy a work by a second-rate Italian artist on a subject of little resonance in Dutch Protestant culture, the simple answer is that it was a learning project. We don’t know very much about Vermeer’s life, but there is no solid evidence that he was ever apprenticed to or tutored by an established artist. Vermeer appears to have taught himself to paint, amazingly enough, and as a highly knowledgeable fan of Italian art and as a recent convert to Catholicism, the 22-year-old artist had reason to appreciate Ficherelli’s original even if his contemporaries did not. Saint Praxedis was a particular favorite of Jesuits in the late 16th century, and Vermeer’s mother-in-law lived next to an order of them in Delft.

As for why Vermeer would copy a work by a second-rate Italian artist on a subject of little resonance in Dutch Protestant culture, the simple answer is that it was a learning project. We don’t know very much about Vermeer’s life, but there is no solid evidence that he was ever apprenticed to or tutored by an established artist. Vermeer appears to have taught himself to paint, amazingly enough, and as a highly knowledgeable fan of Italian art and as a recent convert to Catholicism, the 22-year-old artist had reason to appreciate Ficherelli’s original even if his contemporaries did not. Saint Praxedis was a particular favorite of Jesuits in the late 16th century, and Vermeer’s mother-in-law lived next to an order of them in Delft.

This is one of only two works attributed to Johannes Vermeer that is privately owned, so even though Saint Praxedis doesn’t look much like the works Vermeer is famous for today, the incredibly rare chance to buy any piece by Vermeer could drive the price through the stratosphere.

Well, here in Florence, there are some of us “seicento fiorentino” fanatics who think that Ficherelli is a superstar and the Vermeer attribution a downgrade! Seriously, I remember this picture popping up in shows throughout the 1970s and then disappearing from sight. It will be interesting to see what happens to it at auction. A lot of very odd stuff got sucked into Basha Johnson’s collection and she was cheated outrageously by various art dealers. It will be hilariously funny if a wildly underattributed picture somehow managed to sneak in.

Ooh, intriguing! I wonder how many collectors have found themselves buying pigs in pokes over the years. Attribution is a wild ride, after all.

Anyone interested in Vermeer may want to view the film “Tim’s Vermeer” which was recently released on Netflix. It offers a fascinating look into how Vermeer may have achieved photorealistic effects in some of his paintings. Watching the process also illustrates the subtle and fantastic details to be found in his paintings.

I read about that movie some time ago when it was in theaters and was very much looking forward to seeing it but it never aired near me. I’ve added it to my Netflix queue now. Thank you for the alert! :thanks:

I see the signature on the left side but can’t spot the one on the right. Can anybody see it based on the fairly hi-res photo provided?

I think it’s basically invisible at this point. The Rijksmuseum and Free University experts couldn’t even find it.

A bit off topic: What is that kind of cloth that the ‘sleeping maid’ is having on her table, i.e. the one in the front with the blue bits ? That pattern is definitely not ‘dutch’, but I reckon from either ‘rural Turkey’ or ‘southern America’. My parents used to have a carpet with that pattern, which makes that cloth rather confusing to me. Can anybody help ?

I agree with lineasaved that it looks very much like a Turkish carpet. My parents have one with different colors but the same Space Invaders-like shapes. It is odd that it’s on the table, but that could have been Vermeer’s compositional choice.

I adore Vermeer’s works. So you have raised an important question because I always believed that Vermeer was a rock solid member of the Dutch Reformed Church, despite converting to marry his Catholic wife. If the heart stayed true to the religion he grew up in and loved, the theme he was developing in this painting was unusual for the Netherlands and perhaps counter productive for his career.

He was still very young when he painted Saint Praxedis. Perhaps he was more interested in that point in exploring the iconography of the religion he’d converted to than he would be later.

I own several Turkish carpets, and this resembles them very closely. The Dutch traded all over the world, and this could be from Turkey, no problem; I have a kilim (flat woven blanket/rug) that has similar patterns. Vermeer probably fell in love with the patterns and colors, similar textiles are in “Maid Asleep”.

I agree. It’s the kind of rich texture, color and pattern that couldn’t help but attract the eye of an artist.

That particular carpet shows up in other Vermeer works, as do the chairs. They’re also in the Martha and Mary painting. They are very recognizable. Carpets like these were often draped over tables and hung on walls — they were considered precious objects, not to be used on the floor.

Thanks for this report, adds an unknown (to me) side to Vermeer, one of my favorite artists.

Exciting news on Vermeer! I understand the Rijksmuseum tested the white paint with a “New Method”. Maybe we will see more lost Vermeer paintings

come out of the woodworks from a time when Vermeer was younger and

was finding his unique style..

Cross your fingers!

We will see.