Check out this neat article about the flurry of recent books about the decline and fall of Rome.

It’s by Bryan Ward-Perkins, author of a great decline book of his own, that was the source of the greatest list of all time. His experience gives him an interesting insider’s perspective on what publishers are up to (ie, trying to sell books, of course).

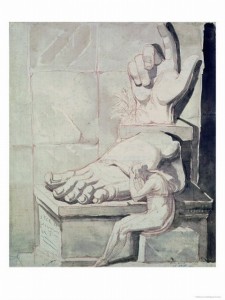

For example, on the left is the cover art he wanted, on the right is the cover art he got:

In the great battle of meditative vs. lurid, lurid wins hands down. (Not that I’m hating, mind you. I dig them both.)

Anyway, the books Perkins profiles offer a variety of theories for the fall, but he thinks they all cluster around a central anxiety.

But it is hard not to conclude that a widespread anxiety over a modern “decline of the West” underlies the presence of all these books on the disintegration of the Roman empire, and of a reading public prepared to buy them. It is certainly very striking that so many books have recently appeared on the dissolution of Rome’s power, and so very few chart its rise and apogee. Europeans, and their descendents the North Americans, have had it very good for four or five centuries, thanks to their dominance (military, political, economic, cultural, even religious) over the globe. Romans had it very good for about the same number of centuries. Then things got a lot more “complicated” for the Romans. Are we in the modern West headed in the same direction?

Most of the six books make explicit and/or implicit analogies between the Roman then and our modern now. James O’Donnell’s The Ruin of the Roman Empire takes a particularly intriguing stance.

His takes is that Eastern Emperor Justinian ruined things for everyone when he invaded Italy and defeated the Ostrogoths who had established a fairly serviceable kingdom after killing the last emperor and sacking the place. From O’Donnell’s perspective, the barbarian Ostrogoths were trying preserve Roman civilization, and Justinian was an impulsive militarist who didn’t think through the long-term consequences of his bellicosity.

Sound like anyone we know? 👿

There’s a reason he was named Theodoric the Great and not just because he did Augustulus in. And Gibbon’s trilogy is still considered the definitive work on the subject- once you get past the 18th century prose and the fact that all Roman and Byzantine emperors shared about five names just to confuse the reader, it’s still a great read. I’m going to send away for O’Donnell’s book today though. Thanks for the lead Livius.

I must admit I still haven’t gotten through all of Gibbon. There’s just so much of it. :blush:

Theodoric didn’t lay a finger on Augustulus, who had been deposed by Odoacer, and lived out his life to a natural death in the gardens of Lucullus at Naples.

I have to confess it took me nine months for all three volumes. It got easier once I got used to the 1770’s English- that was a chore at first. Gibbon was a genius though- taught himself Latin and amassed a personal Library that was extraordinary for his day.

He was a genius, and really, if there is a “decline and fall industry”, he started it. Hell, he named it.

What about continuity and change?

How do you mean?

Yeah, well, I mean, hasn’t the last three decades (at least) been bent on correcting the popular perceptions of a crumbling empire?

Of course, Late Antique studies might be considered as a mere dialectic of the changes that happened from the third to the seventh century in the empire, but I do believe there’s something in it that allows us to see that the empire lived on in the cultures of those who followed the conquest of Rome.

I mostly think that clinging to Gibbon’s Decline and Fall theory is like clinging to geocentrism in the XXth century.

Bryan Ward-Perkins’ book actually addresses that very question. He examines at the decline of quality of life in the wake of imperial fracture through every day commercial items, like roof tiles and pottery.

He shows there was a drastic plunge in the availability and quality of products with the demise of imperial administration, products that aren’t just convenience, but for folks back then could be the difference between misery and comfort.

Perhaps it’s not so cut-and-dried as Gibbon presented it. Standards of living in some areas of the empire (Greece, Syria) continued to thrive for centuries after Italy imploded, for example. But Ward-Perkins makes a persuasive argument that the notion of a crumbling empire was very real for the vast majority of people living under it.

That’s not to say that aspects of the empire didn’t live on in the cultures that replaced it. Of course it did. Hell, it lives on today in our culture, much to my delight. 🙂

:yes: I think too many people automatically associate a crumbling empire (read:government) with a failing society. It’s as if people assume everybody disappeared when the Roman Empire “ended.”

Yes, sadly the “Dark Ages” cliche doesn’t get fleshed out a lot. There was a great variety of political and social circumstances in the areas of former empire.

On the other hand, the population in Europe really did plummet. The city of Rome became a virtual wasteland, going from 1-2 million inhabitants at peak empire to 50,000 after the Gothic Wars of the 6th c.

One interesting static I heard in a Berkley lecture webcast the other day is that until the 10th c., Europe was so sparsely populated that a squirrel could travel from Paris to Moscow just by jumping from tree to tree without ever having to touch the ground. It’s hard to imagine now, isn’t it? 😮

I follow Gibbon in dating the Fall of Rome to 1453 – I don’t know why historians insist it occurred in 476; there is no justification for this. The state that had its capital in Constantinople called itself Rome, was called Rome by all its neighbors, and its people called themselves Romans (Rhomaioi). “Byzantium” was an invention of German historians in the late 16th century.

The Goths were foederati, a barbarian tribe associated with Roman rule, acknowledging it, very like the Franks. Franks and Goths often served in the Roman military, and often commanded it. And now and then (just like Roman generals), they disagreed with the central government and led armies against it. Thus Alaric’s sack of Rome (and the Goths’ slaying of Valens).

Justinian certainly erred in suppressing the Ostrogothic rule of Italy, but he had little reason to think this would be more difficult than overthrowing Vandal rule in Africa had been. (Italian terrain is always tougher than invaders expect.) Both tribes were heretics and therefore tolerated but not accepted by their Roman (Catholic) subjects. But Justinian had no reason to expect the enormous threat from Arabia that appeared less than a century after his death – Rome had never been threatened from that quarter before.

Historians distinguish the Eastern and Western Empire because they had different rulers, a different culture and vastly different historical arcs. The Fall of Rome refers to the city itself and the government that ruled it.

I think it would be disingenuous to say that the Roman Empire was unbroken until 1453 given the massive scale devastation and depopulation on the Western side.

It is not so remarkable that the Roman Empire fell (insofar as it did – the decline lasted a thousand years after all, and few empires last half as long) as it is to examine the reason the Romans were able to acquire such an empire in the first place. The weakness of all their neighbors, once Carthage had been defeated, is a great part of the reason. The Gauls were divided and open to conquest. The Greek states were small and decadent, their armies mercenary and apt to change sides. Rome had a national force that met no opposition until it came up against Parthia. This was an extraordinary stroke of good luck, and enabled the unification of the coasts of the Mediterranean, a triumph of Augustus Caesar, recognized as such at the time. The unified Med lasted until the Vandal conquest of Africa (followed by their taking of Sicily and Sardinia, and their sack of Rome in 455). When the Vandals were suppressed by Justinian and Belisarius, an uneasy unification was restored – until the Arabs took Alexandria (641?) and Carthage, when the unified Med was broken forever.