The Mahin Banu Grape Dish is a serving vessel 17 inches in diameter made during the Ming Dynasty’s Yongle Period in around 1420, and that’s just where the story begins. Its voyage would take it to the royal courts of Persia, the palace of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan during the time when he was building the Taj Mahal in Agra, in the modern era to New York where it starred in exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum, and now to Sotheby’s where it is set to go up for auction at the Important Chinese Works of Art sale on March 17th (short video covering the dish’s design and history here).

The Mahin Banu Grape Dish is a serving vessel 17 inches in diameter made during the Ming Dynasty’s Yongle Period in around 1420, and that’s just where the story begins. Its voyage would take it to the royal courts of Persia, the palace of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan during the time when he was building the Taj Mahal in Agra, in the modern era to New York where it starred in exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum, and now to Sotheby’s where it is set to go up for auction at the Important Chinese Works of Art sale on March 17th (short video covering the dish’s design and history here).

Persian traders were key middlemen in the trade between east and west, so much so that Persian became a common tongue along the Silk Road. As early as the 13th century Chinese porcelain was imported into Iran, and by the early 14th century Chinese kilns were manufacturing porcelain specifically for export to Persia. The demand was great enough that Persian tastes influenced the production of porcelain in China, particularly after the chaos and violence of the Mongol invasions severely inhibited the local market for expensive porcelain goods. Kilns started to produce larger plates than would be used in Chinese food service and included more geometric decorative elements like those seen in Islamic art.

Chinese potters also used Persian raw materials. The cobalt blue that is now so characteristic of Ming porcelain was imported from what is today the Kerman Province of southeastern Iran. When the foreign blue underglaze first began to be used to paint the prized pure white porcelain, in fact, the Chinese elite turned their noses up at it as vulgar and barbarous. Over time they realized it was extremely kickass, and Ming blue-and-white porcelain came to be considered the sine qua non of refinement and elegance.

Chinese potters also used Persian raw materials. The cobalt blue that is now so characteristic of Ming porcelain was imported from what is today the Kerman Province of southeastern Iran. When the foreign blue underglaze first began to be used to paint the prized pure white porcelain, in fact, the Chinese elite turned their noses up at it as vulgar and barbarous. Over time they realized it was extremely kickass, and Ming blue-and-white porcelain came to be considered the sine qua non of refinement and elegance.

The dish probably made its way west to Persia under the Timurid dynasty, founded by famed Timur (aka Tamerlane) in 1370. The Timurid aristocracy loved blue and white porcelain and amassed large collections of pieces from China. The Safavid dynasty, founded in 1501 by Shah Ismail I, carried on the practice of collecting blue-and-white porcelain and it was one of Ismail’s daughters, Princess Mahin Banu Khanum, who put her stamp (figuratively and literally) on the grape dish.

Born in 1519, Mahin Banu was a highly educated, politically savvy, devout woman. She earned a reputation as a patron of the arts, architecture and religious centers. With her own money derived from her properties in Shirvan, Tabriz, Qazvin, Ray and Isfahan, Mahin Banu supported holy shrines and founded charitable organizations, including one dedicated to funding dowries for orphaned girls who would otherwise have been destitute. Her father died in 1524 when she was just five years old, and her 10-year-old brother Tahmasp I came to the throne. A chaotic regency followed which Tahmasp put an end to with the execution of the regent in 1533.

Mahin Banu was Tahmasp’s youngest full sister and his favorite, so much so that she became his right hand, not just socially or in the arts or in a religious context, but politically as well. Mahin Banu was one in a line of unmarried royal Safavid women who became trusted counselors to their brothers and fathers. Without conflicting loyalties, husbands or children to deal with, they could put all of their talents to work helping their relatives. Safavid women of wealth and rank were educated as thoroughly as their brothers. They were tutored in reading, writing, fine art, calligraphy, religion and even martial arts like archery and horseback riding.

Mahin Banu accompanied her brother in the thick of the hunt and sat on horseback by his side during ceremonies when all the other royal women watched from a distance. According to chronicler Qumi’s Khulasat al-Tavarikh, Tahmasp was so dependent on his sister’s counsel that he wouldn’t make a move without seeking her approval first. She was his top advisor in all affairs of state and acted in an official capacity, engaging in diplomatic discussions with Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent’s powerful wife, Hurrem Sultan. She became known as the “Queen of the Age, the Mistress of the time.”

That unmarried status was not happenstance. Tahmasp jealously guarded his sister’s celibacy, chasing off all suitors until he found a permanent solution: a ritual betrothal to Muhammad al-Mahdi, the 12th of the Twelve Imams revered in Shi’a Islam who had died 600 years earlier in the 10th century. Tradition had it that the Mahdi would return again any day — a saddled white horse was left at the palace gate every night just in case — but this engagement wasn’t based on the premise that he’d actually come back and marry the princess. It was a device to prevent her from marrying anyone else and leaving her brother’s side for her husband’s.

Tahmasp shared his sister’s love of art (initially; towards the end of his reign he lost interest). His court created one of the most lavishly illuminated and calligraphied copies of the Shahnameh or Book of Kings, an epic poem recounting the mythical history of the Persian empire written in the 11th century by the poet Ferdowsi, on which the top artists worked for two decades. After the masterpiece was complete, Tahmasp gave it to the Ottoman sultan Selim II as a diplomatic gift on the occasion of his accession to the throne. Contemporary sources record it was part of a train of 34 camels laden with luxurious presents including brocades and other textiles, silk carpets, books and prized porcelain from the far east.

Tahmasp shared his sister’s love of art (initially; towards the end of his reign he lost interest). His court created one of the most lavishly illuminated and calligraphied copies of the Shahnameh or Book of Kings, an epic poem recounting the mythical history of the Persian empire written in the 11th century by the poet Ferdowsi, on which the top artists worked for two decades. After the masterpiece was complete, Tahmasp gave it to the Ottoman sultan Selim II as a diplomatic gift on the occasion of his accession to the throne. Contemporary sources record it was part of a train of 34 camels laden with luxurious presents including brocades and other textiles, silk carpets, books and prized porcelain from the far east.

One of the artists who contributed to Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnameh was painter, master calligrapher and head of the royal library Dust Muhammad who also taught the young Mahin Banu calligraphy, some samples of which have survived and are now in the fabulous wonderland known as the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul. He left the Safavid court in the late 1530s, traveling to Kabul which was ruled by Kamran Mirza, brother of the embattled Mughal emperor Humayun, and then in 1555 went to India by invitation of Humayun himself.

Humayun had had a tough go of it, empire-wise. He became emperor after his father’s death in 1530, but there were disgruntled parties who sought to place his uncle on the throne. He had the armies of two kings looking to reclaim the territory his father had conquered. His brothers, including Kamran Mirza, betrayed him and fought against him repeatedly. He lost much of his Hindustan territory to the forces of Sher Shah Suri and in 1543 retreated to his brother’s lands in what is today Afghanistan. Again his brother was less than supportive, leaving Humayun to seek refuge in Persia where Shah Tahmasp welcomed him with open arms and gave him the royal treatment.

Humayun had had a tough go of it, empire-wise. He became emperor after his father’s death in 1530, but there were disgruntled parties who sought to place his uncle on the throne. He had the armies of two kings looking to reclaim the territory his father had conquered. His brothers, including Kamran Mirza, betrayed him and fought against him repeatedly. He lost much of his Hindustan territory to the forces of Sher Shah Suri and in 1543 retreated to his brother’s lands in what is today Afghanistan. Again his brother was less than supportive, leaving Humayun to seek refuge in Persia where Shah Tahmasp welcomed him with open arms and gave him the royal treatment.

When in 1545 Kamran offered to give Shah Tahmasp Kandahar in exchange for his brother’s body, dead or alive, Tahmasp refused and instead gave Humayun military support against his traitorous older brother. Mahin Banu played a major role in establishing this alliance. Tahmasp had threatened to kill Humayun at one point if he didn’t convert from Sunni to Shi’a Islam, but Mahin Banu convinced her brother to support the Mughal emperor in his attempts to reclaim his territories.

Humayun took Kandahar and Kabul, lost them (he was an awful battlefield general), took them again, and ultimately in 1555 reclaimed Hindustan in large part thanks to the thousands of Persian troops Tahmasp had loaned him. Finally returned to the Mughal throne in Delhi, Humayun invited the Persian artists and craftsmen to do for his empire what he had seen them do during the months he spent traveling in Persia and becoming enamoured with its art and architecture. The Persian influence on Mughal art would long outlast his reign.

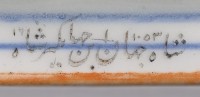

We know that Mahin Banu still owned the grape dish when she died in 1562 because there’s a circular cartouche (vaqf) on the base of the plate that identifies it as having been donated to the Shrine of Imam Reza, the eighth of the Twelve Imams, in Mashhad, as a pious gift. It reads: “Endowed to the Razavid Shrine, By Mahin Banu, the Safavid (princess).” According to 16-17th century chronicler Qazi Ahmad-e Qomi, all of her jewels and her porcelain collection were endowed to the shrine which she had been a dedicated patron of in life.

We know that Mahin Banu still owned the grape dish when she died in 1562 because there’s a circular cartouche (vaqf) on the base of the plate that identifies it as having been donated to the Shrine of Imam Reza, the eighth of the Twelve Imams, in Mashhad, as a pious gift. It reads: “Endowed to the Razavid Shrine, By Mahin Banu, the Safavid (princess).” According to 16-17th century chronicler Qazi Ahmad-e Qomi, all of her jewels and her porcelain collection were endowed to the shrine which she had been a dedicated patron of in life.

The next time the Mahin Banu Grape Dish appears on the historical record is at the Mughal court of Shah Jahan in 1643. Even though Mughal history intersected with Safavid Persia during the period of Mahin Banu’s ownership of the dish and even though she was so closely involved in her brother’s dealings with Humayun, the Ming vessel did not make its way to Agra through the kind of diplomatic channels that had directed 34 camels’-worth of precious objects to Selim II.

So how did the grape dish make its way from a holy shrine to Shah Jahan 80 years later? Probably as war booty that was then traded. The Shrine of Imam Reza was sacked by the Uzbek troops of Abdolmomen Khan in 1590. They picked it clean of all its many treasures, and 17th century Safavid court historian Eskandar Beyg specifically mentions “Chinese vessels” being among the precious objects stolen by the Uzbek soldiers who traded them amongst themselves “for the price of cheap ceramic shards.” Mashhad was reconquered by Shah Abbas I, grandson of Shah Tahmasp, in 1598. (Related factoid: there is only one collection of blue-and-white Ming porcelain from the Safavid dynasty still in Iran today, and it’s that of Shah Abbas I, on display in the National Museum in Tehran.)

So how did the grape dish make its way from a holy shrine to Shah Jahan 80 years later? Probably as war booty that was then traded. The Shrine of Imam Reza was sacked by the Uzbek troops of Abdolmomen Khan in 1590. They picked it clean of all its many treasures, and 17th century Safavid court historian Eskandar Beyg specifically mentions “Chinese vessels” being among the precious objects stolen by the Uzbek soldiers who traded them amongst themselves “for the price of cheap ceramic shards.” Mashhad was reconquered by Shah Abbas I, grandson of Shah Tahmasp, in 1598. (Related factoid: there is only one collection of blue-and-white Ming porcelain from the Safavid dynasty still in Iran today, and it’s that of Shah Abbas I, on display in the National Museum in Tehran.)

It was probably during this period before Jahan acquired the piece that someone tried to erase the vaqf from the bottom of the dish. The inscription marked the vessel as having been endowed to the shrine. Owning it was a violation of Islamic law. Knowing that religiously observant buyers would not purchase the piece because of that, whoever was trying to unload it tried to scratch off the vaqf. Abrasion marks marred the surface, but the inscription was too deep to destroy it completely.

Instead it seems they came up with another cunning plan: cover it up. There are mysterious drill marks on the bottom of the plate that could have been used to add a mount that obscured the incriminating markings. Also, Shah Jahan inscribed his name and the year the dish was acquired on the outer edge of the foot ring. Other Shah Jahan plates have his inscription on the base, which strongly suggests there was something attached down there that made it necessary to move the standard position.

After that, there are no more handy inscriptions on the dish that might illuminate its travels back west. Sotheby’s has a lovely map tracking its known movements like unto Indiana Jones in Raiders which indicates it stopped in Quebec in the late 19th century, but this stop is not referenced in the provenance information. It goes from Shah Jahan to an art dealer in New York and thence into the hands of Alastair Bradley Martin’s and his wife Edith Park Martin’s Guennol Collection in 1967. They loaned it to museums for many years and are now selling it. The pre-sale estimate is $2.5 – 3.5 million. Considering the unbelievably rich history of the piece, its unique version of the grape pattern, its beautiful condition and the sheer madness of the Chinese antiquities market right now courtesy of lots of newly minted Chinese billionaires keen to reclaim cultural heritage scattered by war, trade, looters and time, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if that estimate was left in the dust.

After that, there are no more handy inscriptions on the dish that might illuminate its travels back west. Sotheby’s has a lovely map tracking its known movements like unto Indiana Jones in Raiders which indicates it stopped in Quebec in the late 19th century, but this stop is not referenced in the provenance information. It goes from Shah Jahan to an art dealer in New York and thence into the hands of Alastair Bradley Martin’s and his wife Edith Park Martin’s Guennol Collection in 1967. They loaned it to museums for many years and are now selling it. The pre-sale estimate is $2.5 – 3.5 million. Considering the unbelievably rich history of the piece, its unique version of the grape pattern, its beautiful condition and the sheer madness of the Chinese antiquities market right now courtesy of lots of newly minted Chinese billionaires keen to reclaim cultural heritage scattered by war, trade, looters and time, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if that estimate was left in the dust.

That’s a really clever way for them to dodge social pressure to marry. Everyone at court has to agree that being betrothed to the dead man is ok or deal with the consequences of publicly denying their faith in his imminent return.

Given that her brother always turned to her for advice, I can imagine them cooking it up together after some frustrated sessions of “argh, does everyone have to keep talking about marriage, marriage, marriage!”

Thank you for sharing Mahin Banu’s story, livius!

It’s also an effective way of silencing rumors. There was gossip at court, apparently, that Mahin Banu was getting altogether too chummy with one of Humayun’s generals. Her engagement to the Mahdi nipped all that stuff in the bud.

Hooray! Comments are working again! :boogie:

Yes yay! I kept thinking to myself “I can’t believe nobody dug the story of Mahin Banu. She was so cool.”