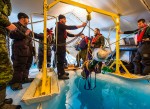

The recent ice dive to the wreck of the HMS Erebus recovered 15 artifacts, including brass buttons from a tunic, ceramic plates and one six-pounder cannon. Pairs of divers — one Parks Canada underwater archaeologist paired with one Royal Canadian Navy ice diving expert — explored the wreck in shifts for 12 hours a day for a week in the middle of April. The original schedule was for two weeks of diving, but weather delays reduced diving time by half.

The recent ice dive to the wreck of the HMS Erebus recovered 15 artifacts, including brass buttons from a tunic, ceramic plates and one six-pounder cannon. Pairs of divers — one Parks Canada underwater archaeologist paired with one Royal Canadian Navy ice diving expert — explored the wreck in shifts for 12 hours a day for a week in the middle of April. The original schedule was for two weeks of diving, but weather delays reduced diving time by half.

The first plan was the remove the tall kelp that had grown around the wreck reducing visibility. With the initial weather delays making a time a factor, the team cut off the kelp only on the port side of the ship.

“It’s tedious, but all of a sudden you have a shipwreck that looks like a wreck site,” says Harris, noting that it was “extremely gratifying to see the shape of the hull as it turns up. You really get a better sense of how big the site is” and how it towers five metres over the sea floor.

“It is so well preserved of course that it does sort of look like a storybook shipwreck.”

They also identified Franklin’s cabin, although they weren’t able to actually enter it.

“We see that that cabin is still there,” says Harris. “It’s just largely crushed between the collapsed upper deck and the lower deck, but you can peer in through… these little spaces where we’re inserting a point-of-view inspection camera.”

Archaeologists saw where artifacts from his cabin fell onto the sea bed. Before they retrieved anything, they made sure to draw a virtual grid of the wreck site so the discovery spots can be documented. The 15 artifacts recovered include a copper alloy (probably brass) 6 1/4″ hook block which may have been part of the ship’s standing rigging or part of the mechanism that lowered the boats, and two illuminators — one brass and glass circular piece, one rectangular glass prism — that were miniature skylights of sorts, installed flush with the upper deck

Archaeologists saw where artifacts from his cabin fell onto the sea bed. Before they retrieved anything, they made sure to draw a virtual grid of the wreck site so the discovery spots can be documented. The 15 artifacts recovered include a copper alloy (probably brass) 6 1/4″ hook block which may have been part of the ship’s standing rigging or part of the mechanism that lowered the boats, and two illuminators — one brass and glass circular piece, one rectangular glass prism — that were miniature skylights of sorts, installed flush with the upper deck  so sailors could walk over them without tripping while they allowed a little light to penetrate the darkness of the lower decks.

so sailors could walk over them without tripping while they allowed a little light to penetrate the darkness of the lower decks.

The three ceramic plates, which are in excellent condition, are fine earthenware pieces with Chinese motifs. One is the “Whampoa” pattern depicting China’s Whampoa Island; the other two are blue willow pattern marked “Royal Patent  Staffordshire China.” Ceramic dishware was a common feature in the officers’ quarters of 18th century Royal Navy ships. This discovery fits with the testimony of an Inuk man named Puhtoorak who in 1879 told members of the search expedition funded by the American Geographical Society and led by explorer Frederick Schwatka that he had seen a ship trapped in the ice off the Adelaide Peninsula and found its contents, including china plates, in perfect order.

Staffordshire China.” Ceramic dishware was a common feature in the officers’ quarters of 18th century Royal Navy ships. This discovery fits with the testimony of an Inuk man named Puhtoorak who in 1879 told members of the search expedition funded by the American Geographical Society and led by explorer Frederick Schwatka that he had seen a ship trapped in the ice off the Adelaide Peninsula and found its contents, including china plates, in perfect order.

The largest object was a brass six-pounder, three of which were known to have been on the Erebus, recovered from the deck of the ship. Its foundry marks are well preserved. They identify it as having been cast by John and Henry King at the Royal Brass Foundry at Woolwich in 1812. A numerical mark “6-0-8” indicates the gun’s weight was 680 pounds.

The largest object was a brass six-pounder, three of which were known to have been on the Erebus, recovered from the deck of the ship. Its foundry marks are well preserved. They identify it as having been cast by John and Henry King at the Royal Brass Foundry at Woolwich in 1812. A numerical mark “6-0-8” indicates the gun’s weight was 680 pounds.

The smallest artifacts may reveal the most personal history: two brass buttons from a navy tunic. They are decorated with a crowned anchor encircled by rope, a laurel wreath and the inscription “ROYAL MARINES.” The last two elements are only present on Royal Marines uniforms, and there were only seven Royal Marines aboard HMS Erebus.

The artifacts were on display over the Victoria Day long weekend, May 14th through the 18th at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec. They are now undergoing conservation at the Park Canada lab where they will be stabilized for eventual long-term display.

The artifacts were on display over the Victoria Day long weekend, May 14th through the 18th at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec. They are now undergoing conservation at the Park Canada lab where they will be stabilized for eventual long-term display.

Many unanswered questions remain, most significantly what caused the ship to sink. Archaeologists are hoping that they’ll find pertinent evidence when they clear the starboard side during the summer dives. The summer expedition doesn’t just have the Erebus to contend with; they’ll also be searching for its companion ship, the HMS Terror. That’s a lot of ground to cover in the short window before the ice returns in September.

Interesting–the plate on the upper right looks like flow blue.

Illuminators are always fun. It seems like people must have taken them for souvenirs when their ships got broken up/decommissioned/sold, because sometimes you’ll still find them in antiques shops, overlooked because browsers tend to go, “What is that? Lump of shaped glass? Eh.” But they came in so many different shapes, with different formulations and qualities… when they were original to the ship, they can tell you a lot about for whom and what the ship was built, and even when and where. :boogie:

Not that any of that is needed for the Erebus, but still.

Thanks, I really appreciate this continuing coverage of news related to the Erebus discovery.

I’ve always been fascinated by the saga of the Franklin Expedition, partly because early polar exploration was nearly always both epic and tragic in scope, and partly because there are few mysteries of this magnitude where so many new discoveries continue to turn up, helping us understand what really happened. It really is unique!

I also feel compelled to mention that Dan Simmons’ excellent novel The Terror enormously increased my fascination with the Franklin Expedition story.

As a recent Canadian citizen I took an interest in where this ship might be. I followed the two articles cited above, earlier stories, and discovered that the location of the wreck was in the Queen Maud Gulf. Google earth had heard of that, so I found it, but I had to track its location down. I came across half a dozen more articles for the general public about this site and the divers, but not one of them gave much about the location and nobody produced a simple map to show where in the world the Franklin went down.

I just went and asked my wife, who taught school in the arctic for five years while in her twenties, and she had never heard of the Queen Maud Gulf. Neither had my step-son who is a university professor, and he grew up and went to university in Canada. If we did not know where this place was, then most other readers won’t know either, and in this case a highly significant part of the story is where it happened.