When African Americans research their genealogy, they often hit what is known as the wall: no records to be found before the 1870 United States Federal Census which was the first to enumerate former slaves. Before that number of slaves he owned was noted under the master’s entry, but it was purely statistical. There were no individual names listed. The first federal census since emancipation recorded the name, location, age, birthplace, familial relationships, marital status, occupation, ability to read and write, the total value of a person’s estate and more. That’s rich information, but it doesn’t link former slaves to their past so it’s usually a dead end for genealogists.

When African Americans research their genealogy, they often hit what is known as the wall: no records to be found before the 1870 United States Federal Census which was the first to enumerate former slaves. Before that number of slaves he owned was noted under the master’s entry, but it was purely statistical. There were no individual names listed. The first federal census since emancipation recorded the name, location, age, birthplace, familial relationships, marital status, occupation, ability to read and write, the total value of a person’s estate and more. That’s rich information, but it doesn’t link former slaves to their past so it’s usually a dead end for genealogists.

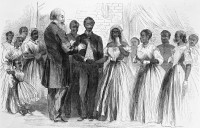

There is one other federal source for precious information on formerly enslaved Americans that predates 1870: the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands was a federal agency created in March of 1865 with the end of the Civil War in sight to help the freed slaves in the 11 states of the Confederacy (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia), border states Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri and the District of Columbia. With four million people free but destitute, the Freedmen’s Bureau ran a relief operation providing food, clothing, medical care and temporary housing in camps. Over the course of its seven years of operation, the Bureau helped freedmen locate family members separated by war and the sale of human beings, founded and supported schools, performed marriages (slave marriages were illegal so the Bureau often solemnized and legalized couples who had been de facto married for years), provided jobs and banking, oversaw labor contracts between former slave owners and former slaves, resettled freedmen on abandoned lands, represented former slaves in court, helped soldiers and sailors secure their back pay and future pensions.

The records generated by the Freedmen’s Bureau therefore cover an immense amount of ground. They include key information like the name of former masters and plantations that would allow genealogists to delve into the pre-Civil War history of African American families. The National Archives has preserved FB records on microfilm and made them available to researchers at the National Archives building in Washington, DC, and at regional archives in California, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington State. Some of the microfilm records have been digitized, but only a fraction of them and without name indexing which would allow people to look up individual family members and pull all their records.

The records generated by the Freedmen’s Bureau therefore cover an immense amount of ground. They include key information like the name of former masters and plantations that would allow genealogists to delve into the pre-Civil War history of African American families. The National Archives has preserved FB records on microfilm and made them available to researchers at the National Archives building in Washington, DC, and at regional archives in California, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, Washington State. Some of the microfilm records have been digitized, but only a fraction of them and without name indexing which would allow people to look up individual family members and pull all their records.

FamilySearch, a non-profit genealogy organization run by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has already digitized some of the Freedman’s Bureau records — 460,000 records of the Freedmen’s Bank, 800,000 records from Virginia — but on Friday, the 150th Juneteenth, it announced a major initiative to digitize and index the names of freedmen recorded in 1.5 million Bureau records. In collaboration with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society and the California African American Museum, the project seeks to mine raw records for names of freedmen and refugees and make the searchable database available for free online.

In order to complete so vast project, FamilySearch is enlisting the power of the crowd. There’s a dedicated website, Discover Freedmen, where volunteers can learn more about the digitization project. If you would like to help digitize the Freedman’s Bureau records, you must first download FamilySearch’s dedicated indexing program and then register an account. A quick introductory video explains how to use the program, but it’s fairly intuitive and user friendly. Once you’re registered and the software is up and running, click the Download Batch button, click Show All Projects and scroll down to US – Freedmen’s Bureau projects. Here’s a list of all the FB batches. There are labor contracts, education records, court records, hospital records, land records, records of complaints, employment, military service claims and rations issued. Only the indexing of the medical records is close to completion; most of the batches have barely been touched.

After you’ve selected a batch, the image of a record will appear in your software. Your job is to scour it for name of anyone who is not a Bureau official and enter any names you find in the appropriate data entry fields. If you have any difficulty reading handwriting, you can view the next and previous documents which might have associated information written more legibly. You can also use the Share Batch feature to enlist the aid of other indexers. If you just can’t make heads or tails of it, you can Return Batch to give it to other indexers.

To get started, download the indexing program here. When you open it up after installation, it will prompt you to register. After that, wade into the records of your choice. If all goes well, the project is expected to take a year after which the records will be exhibited at the opening of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in late 2016. You can search by ancestor name right now on the Discover Freedmen website (click Discover in the header menu), although of course there are many fewer names in the database than there will be next year.

Regarding: ” Millions of Freedmen’s Bureau records digitized”

This is of course a most praiseworthy project.

All attempts to record and preserve history for future generations are important and need to be supported.

However the term “Freedmen’s Bureau” is as inaccurate as stating that ice is hot and fire is cold.

Very, very few Americans and non Americans for that matter, possess even an inkling of real information concerning what was the fate of Black Americans after 1865 and in fact right up to WW II.

One can learn the agonizingly painful real historical realities in the 2009 Pulitzer Prize winning book by Douglas Blackmon, later made into an award winning documentary film.

http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/home/

Slavery by Another Name is a 90-minute documentary that challenges one of Americans’ most cherished assumptions: the belief that slavery in this country ended with the Emancipation Proclamation.

The film tells how even as chattel slavery came to an end in the South in 1865, thousands of African Americans were pulled back into forced labor with shocking force and brutality.

It was a system in which men, often guilty of no crime at all, were arrested, compelled to work without pay, repeatedly bought and sold, and coerced to do the bidding of masters.

Tolerated by both the North and South, forced labor lasted well into the 20th century.

For most Americans this is entirely new history. “Slavery by Another Name” gives voice to the largely forgotten victims and perpetrators of forced labor and features their descendants living today.

Learn the real story of what happened to millions of Black Americans after they were supposedly granted their “freedom” from slavery. This is the story that does NOT appear in a single American Public School History book or almost any book.

Read the book and watch the documentary based on the book, for free.

The Nazi’s often boasted that no person will ever believe the enormity of their crimes.

What was visited on Black Americans from 1865 until 1940 falls into the same category.

For those who want to learn the truth and can deal with the truth “Slavery By Another Name” is required reading and viewing.

Definitely time well spent.

The Film:

http://www.pbs.org/tpt/slavery-by-another-name/home/

The book:

http://www.amazon.com/Slavery-Another-Name-Re-Enslavement-Americans/dp/0385722702

This is huge, livius drusus! What a boon to geneologists, both professional and those individuals looking for their own family history.

May I post this on Facebook, and maybe it will be shared and re-shared to let many people know?

The Freedmen’s Bureau seems to have done a lot of good in its time. Treated people like human beings, imagine that. I guess it was ended with Reconstruction? A pity, it could have helped so many people.

I just noticed your “Share/Save” button with one for Facebook, so I guess we’re meant to share your posts. I’ll go ahead then! Thanks.

Livius, this news has been traveling fast in genealogical circles, but I am pleased to see you give it a boost to an audience who otherwise might not have known about it. Here is a chance for all of us to contribute to a project that has great potential not only in making family connections for people seeking their past, but to illuminate a period in our history for all Americans that still resounds in the character of the American culture.

The records are deeply personal. Until now, most of the people they are about have been anonymous and unreachable. As a historical genealogist, I find myself deeply moved each time I read an original record with information about specific individuals who once lived, with connections to a larger community, and to future generations.

Some of my personal lines have been relatively easy to research. Others have been challenging. One I suspect may never be resolved. But there was one in which I finally, following records, came across the birth record for one of my great-great-great grandmothers. There she was, someone who contributed to who I am, and my siblings, and my children.

By all means, learn as much as you can about the history and impact of slavery. But I assure you that there is nothing like seeing records that give details about individuals and families to make that history concrete. Helping to index these records will do that, and in the process, redress a little of the debt owed to people who made significant contributions to America in countless ways, and still are.