A partial Qur’an manuscript in the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library has been radiocarbon dated to between 568 and 645 A.D., which makes it one of the earliest Qur’ans known to survive, perhaps even the earliest. The Prophet Muhammad lived around 570 to 632 A.D., so the sheep or goat who whose skin was used to make the parchment was his contemporary or died very soon after he did.

A partial Qur’an manuscript in the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library has been radiocarbon dated to between 568 and 645 A.D., which makes it one of the earliest Qur’ans known to survive, perhaps even the earliest. The Prophet Muhammad lived around 570 to 632 A.D., so the sheep or goat who whose skin was used to make the parchment was his contemporary or died very soon after he did.

Muslim tradition holds that the Prophet received the revelations of the angel Gabriel in the last two decades of his life, transmitting them orally to his closest and most trusted companions who memorized them word for word. According to Sunni Islam, Abu Bakr, Muhammad’s father-in-law and after his death the first caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, fearing that the people who memorized the scripture would die before they could pass it down, ordered the verses written down. That text was then used by the third caliph, Uthman Ibn Affan, as the basis for the definitive version of the Qur’an which was widely copied and distributed in 650 A.D., just 18 years after Muhammad died. (The Shi’ite tradition holds Uthman Ibn Affan solely responsible for collecting the revelations into a single written scripture.)

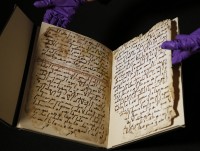

The manuscript consists of two folios with parts of Suras 18 through 20 written in a beautiful tilted Arabic script called Hijazi that is so clear it can be easily read by Arabic readers today. The pages have been in the library for decades, one of more than 3,000 of Middle Eastern manuscripts collected by Chaldean priest Alphonse Mingana in the 1920s at the behest of Edward Cadbury, chocolate magnate in a long line of chocolate magnates who, when they weren’t busy making delicious creme-filled confections, founded a consortium of colleges later absorbed by the University of Birmingham. The folios were mistakenly bound with the folios of another Qur’an written 200 years later in a very similar hand. There are no records of where Mingana acquired these particular leaves, but the parchment and script look like Qur’an fragments from the earliest mosque in Egypt (founded 642 A.D.) that are now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

The manuscript consists of two folios with parts of Suras 18 through 20 written in a beautiful tilted Arabic script called Hijazi that is so clear it can be easily read by Arabic readers today. The pages have been in the library for decades, one of more than 3,000 of Middle Eastern manuscripts collected by Chaldean priest Alphonse Mingana in the 1920s at the behest of Edward Cadbury, chocolate magnate in a long line of chocolate magnates who, when they weren’t busy making delicious creme-filled confections, founded a consortium of colleges later absorbed by the University of Birmingham. The folios were mistakenly bound with the folios of another Qur’an written 200 years later in a very similar hand. There are no records of where Mingana acquired these particular leaves, but the parchment and script look like Qur’an fragments from the earliest mosque in Egypt (founded 642 A.D.) that are now in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Dr. Alba Fedeli noticed the folios while doing research for her PhD. While the handwriting on those two pages at first glance seemed identical to that on the rest of the manuscript, she saw that the content stuck out, that it didn’t seem to fit with what came before and after. Fedeli pointed out the discrepancy to Susan Worrall, director of the library’s special collections, who decided to have them carbon dated by experts at the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. They were shocked by the results.

Dr. Alba Fedeli noticed the folios while doing research for her PhD. While the handwriting on those two pages at first glance seemed identical to that on the rest of the manuscript, she saw that the content stuck out, that it didn’t seem to fit with what came before and after. Fedeli pointed out the discrepancy to Susan Worrall, director of the library’s special collections, who decided to have them carbon dated by experts at the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. They were shocked by the results.

Dr Muhammad Isa Waley, Lead Curator for Persian and Turkish Manuscripts at the British Library, said: “This is indeed an exciting discovery. We know now that these two folios, in a beautiful and surprisingly legible Hijazi hand, almost certainly date from the time of the first three Caliphs. […]

“The Muslim community was not wealthy enough to stockpile animal skins for decades, and to produce a complete Mushaf, or copy, of the Holy Qur’an required a great many of them. The carbon dating evidence, then, indicates that Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library is home to some precious survivors that – in view of the Suras included – would once have been at the centre of a Mushaf from that period. And it seems to leave open the possibility that the Uthmanic redaction took place earlier than had been thought – or even, conceivably, that these folios predate that process. In any case, this – along with the sheer beauty of the content and the surprisingly clear Hijazi script – is news to rejoice Muslim hearts.”

The folios will go on display at University of Birmingham’s Barber Institute of Fine Arts from October 2nd through October 25th.

[youtube=https://youtu.be/C-HDFiC2boQ&w=430]

For older copies of the text, see

Actually, Oldest Qur’ans are in Sanaa, Yemen & in Danger of Saudi Bombing.

It has been pointed out that dating the sheep or goat skin that the text was written on does not tell you when the text itself was written. This is because skins were often cleaned and reused. Furthermore, the manuscripts includes dots and separated chapters which were later innovations according to those in the know.

Why haven’t they dated the ink?

I would love to hear the take of Erik Kwakkel on this find.

While it is true that parchments were often scraped and reused, that is readily evident on the parchment. And given the preciousness of the Qur’an and the desire to retain the words for posterity, I kind of doubt that recycled parchment would have been used.

One of my goals this summer is to read the Qur’an. I read it as a young person, but methinks that it is past time to renew my awareness, so important today.

“And given the preciousness of the Qur’an and the desire to retain the words for posterity …”: you’re assuming that that was true when that was written.

*Grumbles.* Diacriticals…

*Thoughtful.* I wonder if this has something to do with the sudden plurality of Muslim conferences. The occidental groups haven’t multiplied, but their conferences suddenly have.

You are correct that carbon dating alone is not reliable if used exclusively.Epigraphy is also used in order to tie in the carbon dating with the written style for that era. Further more you are incorrect when you say dialectic marks did not exist at the time of the Quran as recent studies have indicated that is not the case. Robert Hoyland, a professor of Arabic and Middle East Studies has commented on a pre-Islamic inscription That has dialectic marks. I have listen the actual English translation of the inscription if you wish to search for it.

“In the name of Allah/ I, Zuhayr, wrote (this) at the time ‘Umar died/year four/And twenty.”