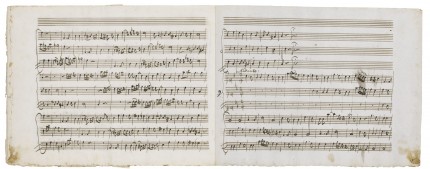

A rare autograph manuscript of a piece of music transcribed by Wolfgang Mozart in around 1773 when he was 17 years old has been acquired by the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation and is now on display at the Salzburg Festival. A transcription of Stabat Mater a 3 voci in canone (Stabat Mater with three voices in canon) by Marchese Eugenio di Ligniville, musical director of the royal court of Tuscany, the manuscript is 12 pages long and is in the hand of Wolfgang Mozart with annotations by his father Leopold. It has been in private collections since the 1920s. The Foundation was able to buy the manuscript for £167,000 ($256,796) when it came up for auction at Sotheby’s London in May thanks to a generous gift from an anonymous donor.

Time for a little digression through the labyrinth of European political history. Remember Anna Maria de’ Medici, Electress Palatine, who saved Florence’s artistic patrimony after the last Medici grand duke died leaving the grand duchy in the hands of the future Holy Roman Emperor Francis I? The Medici had ruled Florence off and on since the 15th century, but after the troops of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked Rome in 1527, the Medici’s enemies took advantage of the chaos to overthrow the family and reinstall a Republic with rotating leadership. When Pope Clement VII, born Giulio di Giuliano de’ Medici, made peace with Charles V in 1539, Charles agreed to reclaim Florence for the pope’s family. It took 11 months of siege to do it, but in 1530 Florence fell. Tuscany became a fiefdom of the Holy Roman Emperor and the pope’s illegitimate nephew Alessandro Medici was installed as its ruler. Charles made it official by stipulating that from then on, Tuscany would be ruled in perpetuity by the male heirs of the Medici family.

So, when Gian Gastone, Anna Maria’s brother and the last male direct descendant of the main family branch, died, a more distant relative had to be installed. There were several strong candidates — the Medici married and bred very well and very copiously — but Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI wasn’t a principled genealogist seeking the closest male heir. He had other priorities, placating the deposed King of Poland Stanisław Leszczyński, father of the Queen of France, being one of them. Getting his daughter and heir Maria Theresa married to someone he liked who could support her in the inevitable succession war after Charles’ death was an even bigger one. Tuscany was the stone with which he hit both those birds.

So, when Gian Gastone, Anna Maria’s brother and the last male direct descendant of the main family branch, died, a more distant relative had to be installed. There were several strong candidates — the Medici married and bred very well and very copiously — but Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI wasn’t a principled genealogist seeking the closest male heir. He had other priorities, placating the deposed King of Poland Stanisław Leszczyński, father of the Queen of France, being one of them. Getting his daughter and heir Maria Theresa married to someone he liked who could support her in the inevitable succession war after Charles’ death was an even bigger one. Tuscany was the stone with which he hit both those birds.

Francis, Duke of Lorraine, scion of an ancient noble French house and second cousin to the Holy Roman Emperor, could claim descendance from Catherine de’ Medici, at various times queen consort, queen mother and regent of France, through her daughter Claude of Valois. Relying on the female line, his claim to the throne of Tuscany was one of the weaker ones. It was strengthened immeasurably by the fact that Charles wanted Francis to marry his daughter.

In order to marry Maria Theresa, Francis would have to give up the Duchy of Lorraine, something he was extremely reluctant to do. His family was vociferously opposed to him giving up his birthright, not even for an empire. In the treaty negotiations after the War of the Polish Succession, France would only agree to support Charles’ Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 (the edict that allowed women to inherit Hapsburg lands and titles) if the fiance’ of the woman in question gave the Duchy of Lorraine to Stanisław Leszczyński for his lifetime, after which it would become property of the French crown. To sweeten the deal, Charles VI offered Francis the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in exchange for his lost Lorraine. He took it.

In order to marry Maria Theresa, Francis would have to give up the Duchy of Lorraine, something he was extremely reluctant to do. His family was vociferously opposed to him giving up his birthright, not even for an empire. In the treaty negotiations after the War of the Polish Succession, France would only agree to support Charles’ Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 (the edict that allowed women to inherit Hapsburg lands and titles) if the fiance’ of the woman in question gave the Duchy of Lorraine to Stanisław Leszczyński for his lifetime, after which it would become property of the French crown. To sweeten the deal, Charles VI offered Francis the Grand Duchy of Tuscany in exchange for his lost Lorraine. He took it.

Grand Duke Francesco only alighted in Florence once for three months in 1739. The rest of the time the grand duchy was ruled by his viceroy Marc de Beauvau, Prince of Craon, who was married to Anne Marguerite de Lignéville. After Francis’ death in 1765, his son Peter Leopold became grand duke of Tuscany. Eugenio di Ligniville, a relative of the former viceroy’s wife and one of many nobles from Lorraine who moved to Tuscany after Gian Gastone’s death in 1737, became director of music to the court of Tuscany in 1768. Ligniville was not a professional musician. He had served as the grand duchy’s postmaster general until retiring in 1767. He was an accomplished composer and music theorist nonetheless with an international reputation as a master of counterpoint.

The Stabat Mater a 3 voci in canone was first published in 1767 and was acclaimed as the pinnacle of art of counterpoint by Franciscan friar and leading composer of the period Padre Giovanni Battista Martini. Martini wrote a letter to Ligniville in March of 1767 complimenting on his canon. He wrote that he considered counterpoint to be the hardest and most essential exercise for any musician truly seeking to improve their abilities and understanding of composition, and lamented its falling out of favor in the education of musicians of their century.

The Stabat Mater a 3 voci in canone was first published in 1767 and was acclaimed as the pinnacle of art of counterpoint by Franciscan friar and leading composer of the period Padre Giovanni Battista Martini. Martini wrote a letter to Ligniville in March of 1767 complimenting on his canon. He wrote that he considered counterpoint to be the hardest and most essential exercise for any musician truly seeking to improve their abilities and understanding of composition, and lamented its falling out of favor in the education of musicians of their century.

In his role as music director, Ligniville arranged for Leopold and the 14-year-old Wolfgang Mozart to visit the Tuscan court in April of 1770. Father and son were received by the Grand Duke at Palazzo Pitti on April 1st. The next day the grand duke sent his carriage to transport them to his summer villa of Poggio Imperiale where Wolfgang performed. The performance was stellar, according to the Wolfgang’s father Leopold, and their ample reward from the Grand Duke of 333.6.8 Lire or 25 gold zecchini supports the contention. From a letter he wrote to his wife in Salzburg:

“Everything went off as usual and the amazement was all the greater as Marchese Ligniville, the director of music, who is the finest expert in counterpoint in the whole of Italy, placed the most difficult fugues before Wolfgang and gave him the most difficult themes, which he played off and worked out as easily as one eats a piece of bread. Nardini, that excellent violinist, accompanied him.”

After that, the pair traveled around Italy, until reaching Bologna in July where Wolfgang took lessons in counterpoint from Padre Martini for three months. The lessons obviously kept going even when they returned to Salzburg, because the transcription of Ligniville’s Stabat Mater was done in 1773. One of things that makes the manuscript so important is that it captures the young artist in the very act of mastering the finer technical points of the composer’s craft. From the Sotheby’s catalog note:

After that, the pair traveled around Italy, until reaching Bologna in July where Wolfgang took lessons in counterpoint from Padre Martini for three months. The lessons obviously kept going even when they returned to Salzburg, because the transcription of Ligniville’s Stabat Mater was done in 1773. One of things that makes the manuscript so important is that it captures the young artist in the very act of mastering the finer technical points of the composer’s craft. From the Sotheby’s catalog note:

The importance of the manuscript lies particularly in the light it sheds on Mozart’s contrapuntal studies, complementing as it does the scattered complex of manuscripts … in which Mozart wrestled with the puzzle canons from Padre Martini’s Storia della musica. When in 1785 Joseph Haydn famously stated to Leopold Mozart, then visiting his son in Vienna, that Mozart possessed ‘taste and, what is more, the most profound knowledge of composition’, he was stating no more than the truth. [This] autograph … is a testament to the fact that such knowledge was not acquired easily by Mozart, but rather was the result of painstaking and concentrated effort.

Oh go on with you. Why, with ten thousand hours of practice I could have been a Mozart. And if you don’t believe me, ask any simpleton of your acquaintance.

You have a great blog here! would you like to make some invite posts on my blog?