The ancient Greek city-state of Corinth was fortuitously located on the well-traveled isthmus that connects the Peloponnese peninsula to mainland Greece, but it was three miles inland. To take advantage of its central position on the narrow isthmus, Corinth built two ports: Lechaion to the north for maritime trade headed west towards Italy and Kenchreai to the south for maritime trade headed east towards Asia Minor and Egypt. Corinth’s control of the isthmus ensured it remained a dominant economic and military power in the region from classical Greece through the Byzantine period.

The ancient Greek city-state of Corinth was fortuitously located on the well-traveled isthmus that connects the Peloponnese peninsula to mainland Greece, but it was three miles inland. To take advantage of its central position on the narrow isthmus, Corinth built two ports: Lechaion to the north for maritime trade headed west towards Italy and Kenchreai to the south for maritime trade headed east towards Asia Minor and Egypt. Corinth’s control of the isthmus ensured it remained a dominant economic and military power in the region from classical Greece through the Byzantine period.

The harbour town of Lechaion on the Gulf of Corinth, therefore, was a prosperous hub of Mediterranean maritime trade for more than 1,000 years, in continuous use from the 6th century B.C. to the 6th century A.D. The remains of the ancient harbour are underwater now and until recently were barely explored. The Lechaion Harbour Project (LHP), an international collaboration between the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the University of Copenhagen and the Danish Institute at Athens, seeks to remedy this oversight. Their marine archaeologists have been exploring the ruins of Lechaion for the past two years, while geologists use the latest technology to do a geophysical survey of the seabed. The newly developed 3D parametric sub-bottom profiler will allow them to capture 3D images of structures hidden underneath the sand.

The harbour town of Lechaion on the Gulf of Corinth, therefore, was a prosperous hub of Mediterranean maritime trade for more than 1,000 years, in continuous use from the 6th century B.C. to the 6th century A.D. The remains of the ancient harbour are underwater now and until recently were barely explored. The Lechaion Harbour Project (LHP), an international collaboration between the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities, the University of Copenhagen and the Danish Institute at Athens, seeks to remedy this oversight. Their marine archaeologists have been exploring the ruins of Lechaion for the past two years, while geologists use the latest technology to do a geophysical survey of the seabed. The newly developed 3D parametric sub-bottom profiler will allow them to capture 3D images of structures hidden underneath the sand.

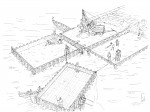

Last year, the LHP team discovered massive squared blocks that were once part of two monumental piers, a smaller pier, a breakwater, the stone-lined entrance canal into the inner harbor basins and most remarkably, the remains of six wooden caissons. The Lechaion caissons were large wooden barges laden with concrete which were floated out to a specific area and deliberately sunk together to create a breakwater to protect moored ships and their cargoes from wind and surf. All together the surviving caissons are 57 meters (187 feet) long.

Last year, the LHP team discovered massive squared blocks that were once part of two monumental piers, a smaller pier, a breakwater, the stone-lined entrance canal into the inner harbor basins and most remarkably, the remains of six wooden caissons. The Lechaion caissons were large wooden barges laden with concrete which were floated out to a specific area and deliberately sunk together to create a breakwater to protect moored ships and their cargoes from wind and surf. All together the surviving caissons are 57 meters (187 feet) long.

Roman imperial engineers employed a similar technology on a large scale at Caesarea Maritima in Israel in the late first century BC, but these are the first of their kind ever discovered in Greece with their wooden elements still preserved. A preliminary C-14 carbon date places the caissons in the time frame of the Leonidas Basilica, the largest Christian church of its time. Construction of the basilica began in the middle of the 5th century AD. It was 180 meters long – about the same size as the first building phase of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Scholars generally assume that harbour facilities in the Mediterranean were built in the Greek and Roman period, then simply repaired and maintained during the Byzantine period. The discovery of the mole constructed of wooden caissons challenges this picture.

Through no fault of its own, the newly discovered Byzantine construction was not long-lived. Lechaion was destroyed in the late 6th or early 7th century A.D. It’s an archaeological miracle that any part of the caissons survived. The warm water and high salt concentration of the Mediterranean make it a paradise for woodworm. They can devour wood and other organic materials in a matter of months. Before this discovery, only traces of the presence of caissons have been found, the wood itself having long since decayed.

Through no fault of its own, the newly discovered Byzantine construction was not long-lived. Lechaion was destroyed in the late 6th or early 7th century A.D. It’s an archaeological miracle that any part of the caissons survived. The warm water and high salt concentration of the Mediterranean make it a paradise for woodworm. They can devour wood and other organic materials in a matter of months. Before this discovery, only traces of the presence of caissons have been found, the wood itself having long since decayed.

Danish archaeologist Bjorn Lovén of the University of Copenhagen first spotted the caissons on a dive.

“I swam in full diving equipment and suddenly saw lots of planks and poles on the sea bed, and my heart skipped a beat. First I was skeptical, because it was almost too good to be true. But deep down I knew, that it had to be antique wood for building, since no one [built] harbours that way later on. Still I was in doubt, until we got it confirmed.”

The wood is in shockingly good condition, which gives the archaeologists hope they’ll find more organic material in the inner and outer harbour, maybe even one of the Holy Grails of maritime archaeology: the trireme, a warship with three banks of oars which was instrumental in Greece’s victory in the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century B.C. Ancient sources like Thucydides, Pliny and Diodorus Siculus claim triremes were invented in Corinth. Thucydides notes in The History of the Peloponnesian War that the Corinthian shipbuilder Ameinokles made four of them for the Samians in the 8th century B.C. The ruins of trireme shipsheds have been found at the ancient Athenian harbour of Piraeus, but not the ships themselves. The discovery of so much surviving wood from the caissons makes it a possibility, albeit a very remote one, that the LHP team might one day find the remains of a trireme.

The wood is in shockingly good condition, which gives the archaeologists hope they’ll find more organic material in the inner and outer harbour, maybe even one of the Holy Grails of maritime archaeology: the trireme, a warship with three banks of oars which was instrumental in Greece’s victory in the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century B.C. Ancient sources like Thucydides, Pliny and Diodorus Siculus claim triremes were invented in Corinth. Thucydides notes in The History of the Peloponnesian War that the Corinthian shipbuilder Ameinokles made four of them for the Samians in the 8th century B.C. The ruins of trireme shipsheds have been found at the ancient Athenian harbour of Piraeus, but not the ships themselves. The discovery of so much surviving wood from the caissons makes it a possibility, albeit a very remote one, that the LHP team might one day find the remains of a trireme.

There are some great views of the wood caissons in this video:

aah! Those two swimmers in the corner in the drawing make me feel super nervous. Get out of there before you get squished!

Man, that overhead shot at the end of the video is great. Such context.

If Triremes are what they looking for, Salamis a few meters to the East might be an option.