In July of 2014, archaeologists investigating the man-made caves tunneled into the limestone plateau under Naours, in Picardy, northern France, discovered thousands of graffiti left by soldiers during World War I. The original brief of the exploration was to date the caves more accurately and identify the periods they were in use. Those questions were answered. The epicenter of the network was

In July of 2014, archaeologists investigating the man-made caves tunneled into the limestone plateau under Naours, in Picardy, northern France, discovered thousands of graffiti left by soldiers during World War I. The original brief of the exploration was to date the caves more accurately and identify the periods they were in use. Those questions were answered. The epicenter of the network was  Roman quarries with tunnels dug starting in the 10th century radiating out from it. Over time, the network of caves covered more than 2,000 meters (1.24 miles), large enough to shelter people and livestock during times of strife, most notably the 16th century Wars of Religion and the Thirty Years’ War in the early 17th century. Local families claimed chambers as their own, engraving their names on the walls.

Roman quarries with tunnels dug starting in the 10th century radiating out from it. Over time, the network of caves covered more than 2,000 meters (1.24 miles), large enough to shelter people and livestock during times of strife, most notably the 16th century Wars of Religion and the Thirty Years’ War in the early 17th century. Local families claimed chambers as their own, engraving their names on the walls.

The entrance to the tunnels was blocked by a cave-in in the early 19th century and the underground city was largely forgotten until December 15th, 1887, when Abbot Ernest Danicourt rediscovered it. He spent years clearing the tunnels to make them accessible and created displays of artifacts he had found there to attract tourism to the area. Abbot Danicourt’s efforts were not vain, and by the early 20th century, the Naours Caves were an internationally known tourist attraction.

The entrance to the tunnels was blocked by a cave-in in the early 19th century and the underground city was largely forgotten until December 15th, 1887, when Abbot Ernest Danicourt rediscovered it. He spent years clearing the tunnels to make them accessible and created displays of artifacts he had found there to attract tourism to the area. Abbot Danicourt’s efforts were not vain, and by the early 20th century, the Naours Caves were an internationally known tourist attraction.

When they were reopened in the 1930s, guides claimed the caves had been used by Allied forces in World War I as a military hospital. That story was apocryphal. Other tunnel networks in the region were used as hospitals and living quarters for the troops, but not Naours. And yet, World War I troops certainly left their marks on the walls and then some. The discovery was so momentous that Gilles Prilaux, an archaeologist with the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), shifted the focus of his investigations away from the more remote past of the caves to the Great War graffiti.

When they were reopened in the 1930s, guides claimed the caves had been used by Allied forces in World War I as a military hospital. That story was apocryphal. Other tunnel networks in the region were used as hospitals and living quarters for the troops, but not Naours. And yet, World War I troops certainly left their marks on the walls and then some. The discovery was so momentous that Gilles Prilaux, an archaeologist with the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), shifted the focus of his investigations away from the more remote past of the caves to the Great War graffiti.

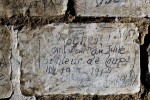

Two years later, we now know the final tally: there are more than 2,800 individual soldiers’ names. Most of them are accompanied by the person’s nationality and military unit and the date. The troops came from France, Britain, America, Canada, India, New Zealand and Australia. About half of the names belong to Australian soldiers. They were written on the wall with lead pencils which has stood the test of time; most of the graffiti are as dark and legible as they day they were made.

Two years later, we now know the final tally: there are more than 2,800 individual soldiers’ names. Most of them are accompanied by the person’s nationality and military unit and the date. The troops came from France, Britain, America, Canada, India, New Zealand and Australia. About half of the names belong to Australian soldiers. They were written on the wall with lead pencils which has stood the test of time; most of the graffiti are as dark and legible as they day they were made.

Students from the local college led by an INRAP archaeologists have worked assiduously to document the graffiti and find out all they can about the men who left their names on the wall. They were able to compile biographies of dozens of the soldiers, several of them very well known.

One of the men identified proved to be a rich source of information. “A. Allsop” wrote the date, January 2nd, 1917, and his hometown of Mosman, a Sydney suburb, on one of the most crowded walls. He was William Joseph Allan Allsop, an Australian clerk who kept detailed diaries of his daily life during World War I. Allsop’s diaries are now in the State Library of New South Wales and have been digitized. When the team looked up the diary entry for January 2nd, they found this:

One of the men identified proved to be a rich source of information. “A. Allsop” wrote the date, January 2nd, 1917, and his hometown of Mosman, a Sydney suburb, on one of the most crowded walls. He was William Joseph Allan Allsop, an Australian clerk who kept detailed diaries of his daily life during World War I. Allsop’s diaries are now in the State Library of New South Wales and have been digitized. When the team looked up the diary entry for January 2nd, they found this:

In the afternoon a party of 10 of us went for a trip to the famous caves near Naours where the refugees used to hide in time of invasion. These caves contain about 300 rooms – one cave being ½ mile long. A whole division of troops with horses, artillery and all transport could be put into these caves. The names of John Norton & Eva Pannett are to be seen autographed on the stone erected just inside the entrance.

While we tend to think of World War I soldiers as constantly mired in waterlogged trenches or active slaughter, according to Prilaux in fact most soldiers spent about 20% of their time on the front lines. The other 80% was spent training, getting some R&R or enjoying the local attractions/distractions. A trip to the caves of Naours like the one Allan Allsop and nine of his comrades took the day after New Year’s would have been encouraged by the military command to keep troops’ minds off the war.

While we tend to think of World War I soldiers as constantly mired in waterlogged trenches or active slaughter, according to Prilaux in fact most soldiers spent about 20% of their time on the front lines. The other 80% was spent training, getting some R&R or enjoying the local attractions/distractions. A trip to the caves of Naours like the one Allan Allsop and nine of his comrades took the day after New Year’s would have been encouraged by the military command to keep troops’ minds off the war.

The day before Allsop and his pals visited the caves, Lieutenant Leslie Russel Blake left his name, unit and the date on the wall. Blake had made a name for himself as a cartographer, geologist and Antarctic explorer in the years before the war. He mapped Macquarie Island from 1911 to 1913 as part of Sir Douglas Mawson’s expedition to map a large unexplored section of the Antarctic coastline. Blake enlisted in 1915, was quickly promoted and arrived on the Western Front in March of 1916 as a second lieutenant. He was awarded the Military Cross for using his mapping skills under heavy fire to survey the Allied front line during the Battle of the Somme. His accuracy and bravery saved many lives.

The day before Allsop and his pals visited the caves, Lieutenant Leslie Russel Blake left his name, unit and the date on the wall. Blake had made a name for himself as a cartographer, geologist and Antarctic explorer in the years before the war. He mapped Macquarie Island from 1911 to 1913 as part of Sir Douglas Mawson’s expedition to map a large unexplored section of the Antarctic coastline. Blake enlisted in 1915, was quickly promoted and arrived on the Western Front in March of 1916 as a second lieutenant. He was awarded the Military Cross for using his mapping skills under heavy fire to survey the Allied front line during the Battle of the Somme. His accuracy and bravery saved many lives.

He almost made it out of the war alive, but on October 2nd, 1918, Blake was hit by a shell in Hargicourt. The blow took his left leg and killed his horse out from under him. He was treated at a field hospital, his leg amputated above the knee, but it could not save his life. The shell had fractured his skull and peppered his face and body with grievous wounds. He died on October 3rd at 6:10 AM and was buried in the New British Cemetery at Tincourt.

He almost made it out of the war alive, but on October 2nd, 1918, Blake was hit by a shell in Hargicourt. The blow took his left leg and killed his horse out from under him. He was treated at a field hospital, his leg amputated above the knee, but it could not save his life. The shell had fractured his skull and peppered his face and body with grievous wounds. He died on October 3rd at 6:10 AM and was buried in the New British Cemetery at Tincourt.

The stories behind the graffiti discovered by the students will be shared with their counterparts at an Australian college in the hopes that descendants and relatives of the men who took a break from mud, blood and horror to visit the caves of Naours might be located.

Excellent (HD) map here: http://citesouterrainedenaours.fr/cite-souterraine-naours/

Am presently working on this project……would like more details and contacts if possible……..am working with Vignacourt and Villers Brocage

Regards

Michael