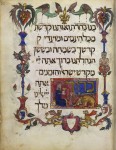

A fragment of 13th century pottery unearthed in Teruel, Aragon, eastern Spain, has been identified as a rare depiction of a Jewish man. The fragment was discovered in 2004, one of thousands that were squirreled away for later documentation. It was catalogued in 2011 but the image was only recognized as a Jewish figure this year by archaeologist Antonio Hernandez Pardos. This is a very rare find. Most surviving images of Spanish Jews from the Middle Ages are illuminations in Haggadot or Christian prayer books.

A fragment of 13th century pottery unearthed in Teruel, Aragon, eastern Spain, has been identified as a rare depiction of a Jewish man. The fragment was discovered in 2004, one of thousands that were squirreled away for later documentation. It was catalogued in 2011 but the image was only recognized as a Jewish figure this year by archaeologist Antonio Hernandez Pardos. This is a very rare find. Most surviving images of Spanish Jews from the Middle Ages are illuminations in Haggadot or Christian prayer books.

Unusual for pottery decorations from that period, which mostly featured geometric shapes or depiction of flowers, the Teruel fragment shows the lower part of the face of a bearded man wearing a frilled gown that Pardos was able to trace back to Jewish iconography from the period. […]

The research by Pardos suggests the fragment was part of a work performed by the earliest known potters of Teruel, who were possibly commissioned by a Jewish resident of the area.

Founded in 1170 by Alfonso II of Aragon on the border between his kingdom and Muslim Spain, Teruel flourished during the second third of the 13th century after King James I of Aragon conquered Xarq-al-Andalus, the Levante or eastern region of the Iberian peninsula. Under James I’s relatively enlightened rule, Jews and Moors moved from less tolerant climes and settled in Teruel. The earliest documentary evidence of Jews living in Teruel dates to 1258 when James I confirmed the Jewish community’s tax obligations to the crown. The first written reference to actual members of Teruel’s Jewish community comes 11 years later. It mentions Dueña del Cano and her late husband Samuel Najarí, an important money lender who was one of the crown’s top creditors.

Founded in 1170 by Alfonso II of Aragon on the border between his kingdom and Muslim Spain, Teruel flourished during the second third of the 13th century after King James I of Aragon conquered Xarq-al-Andalus, the Levante or eastern region of the Iberian peninsula. Under James I’s relatively enlightened rule, Jews and Moors moved from less tolerant climes and settled in Teruel. The earliest documentary evidence of Jews living in Teruel dates to 1258 when James I confirmed the Jewish community’s tax obligations to the crown. The first written reference to actual members of Teruel’s Jewish community comes 11 years later. It mentions Dueña del Cano and her late husband Samuel Najarí, an important money lender who was one of the crown’s top creditors.

Jews in Teruel thrived in the 13th and 14th centuries, engaging in a variety of trades, particularly weaving and dealing wool. Several prominent Jewish scholars lived in Teruel. Things took a dark turn at the end of the 14th century. A delator (informer or denunciator) arrived in 1385, presaging the pogroms and riots of 1391 which spread through Spain like wildfire and resulted in the murder of thousands of Jews and forced conversions of thousands more. That bloody year was a turning point for Jews in Christian Spain. More and more laws were enacted against them, prohibiting money-lending, commerce with Christians, wearing the same clothes as Christians and forcing them into walled Juderías. Many Jews fled south to the more tolerant areas of al-Andalus. The Jewish community of Teruel was diminished but survived until 1492 when the last bastion of Muslim Spain, the Emirate of Grenada, fell and all of Spain’s Jews were either forced to convert to Christianity or expelled from the realm.

The small fragment of pottery is of outsized significance because despite the distinctiveness of the Jewish community in medieval Spain, with its unique legal status, designated living areas and particular religious/cultural traditions, there are few clear markers of Jewishness in the material culture. There’s no immediately identifiable Jewish architecture like there is Islamic architecture, no immediately identifiable ceramic tradition distinct from Christian or Islamic crafts. The exception is in objects of religious meaning and ritual purpose, but everyday things with an unmistakable Jewish identity are very rare in any period, all the more so in the first few decades of Jewish presence in Teruel.

The small fragment of pottery is of outsized significance because despite the distinctiveness of the Jewish community in medieval Spain, with its unique legal status, designated living areas and particular religious/cultural traditions, there are few clear markers of Jewishness in the material culture. There’s no immediately identifiable Jewish architecture like there is Islamic architecture, no immediately identifiable ceramic tradition distinct from Christian or Islamic crafts. The exception is in objects of religious meaning and ritual purpose, but everyday things with an unmistakable Jewish identity are very rare in any period, all the more so in the first few decades of Jewish presence in Teruel.

This lacuna widened into a chasm during the Spanish Civil War when Teruel was the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the war. Fought over three months from December of 1937 through February of 1938, the Battle of Teruel devastated the city, subjecting it to constant artillery barrages and aerial bombardment. Tens of thousands of people died before the Nationalists finally won. Large sections of the medieval center of the city were destroyed, and what had once been the Jewish Quarter was all but leveled.

This lacuna widened into a chasm during the Spanish Civil War when Teruel was the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the war. Fought over three months from December of 1937 through February of 1938, the Battle of Teruel devastated the city, subjecting it to constant artillery barrages and aerial bombardment. Tens of thousands of people died before the Nationalists finally won. Large sections of the medieval center of the city were destroyed, and what had once been the Jewish Quarter was all but leveled.

The war-damaged areas were extensively developed in subsequent decades. The Jewish Quarter was rediscovered in 1978 when the ruins of a building abutting its central square and three menorahs were unearthed. The structure was built in the mid-14th century when the neighborhood was going through a third phase of improvement. The large cellar built on powerful masonry arches discovered in 1978 was initially believed to be a synagogue because of its impressive size and strength. The Jewish Quarter wasn’t fully explored archaeologically until 2004 when a major urban renewal project in the plaza area provided the first opportunity for a proper archaeological survey of the site. The excavation revealed several layers of pottery fragments which gave archaeologists new insight into the evolution of the neighborhood in the 13th century, from the perspective of both use and production of ceramics.

The war-damaged areas were extensively developed in subsequent decades. The Jewish Quarter was rediscovered in 1978 when the ruins of a building abutting its central square and three menorahs were unearthed. The structure was built in the mid-14th century when the neighborhood was going through a third phase of improvement. The large cellar built on powerful masonry arches discovered in 1978 was initially believed to be a synagogue because of its impressive size and strength. The Jewish Quarter wasn’t fully explored archaeologically until 2004 when a major urban renewal project in the plaza area provided the first opportunity for a proper archaeological survey of the site. The excavation revealed several layers of pottery fragments which gave archaeologists new insight into the evolution of the neighborhood in the 13th century, from the perspective of both use and production of ceramics.

There are boxes full of fragments from this excavation that haven’t been studied yet. Pardos expects there are more happy surprises to be found in there. His study of the fragment has been published in the journal Sefarad and can be accessed free of charge here (Spanish language pdf).

Hey,

I’m one of your fellow history nerds and I’ve been needing to thank you for your blog. So much interesting stuff out there and I really appreciate the time you put into this. I teach women’s studies and I do a weekly mailing list for my students so I have an inkling of how much time you put into this. Also just wondering if you’re okay with people reblogging your posts on Tumblr. I know a lot of people would love this one. Cheers and thanks again,

Shaindy

I’m totally okay with people reblogging my posts on Tumblr. Every once in a while I follow an incoming link to Tumblr and I get a kick out of the comments.

Thank you for your kind words. :thanks:

Wow! An intriguing discovery, to be sure. Hernandez Pardos’ article is quite fascinating–with its exploration of the social, historical and iconographical context of the bowl. He proposes that the other partial figure in the fragment is an adolescent Jewish male–since a woman would not likely be shown with long uncovered hair. And now, we have to wonder what else is lurking in the hoard of fragments from Teruel–and how many other Jews remain elsewhere in archeological oblivion.

I’m secretly hoping they find enough fragments from the same bowl to piece most of it back together. I’m double-secretly hoping that it’s part of a whole set or a series of similar pieces capturing Jewish images from daily life in ceramic. I know it’s unlikely, but la speranza e’ l’ultima a morire, am I right?

Excellent discovery!

If large sections of the medieval heart of Teruel, Aragon city were destroyed, then I imagine that all architecture, books and cultural objects of the city disappeared. Particularly so if the Jewish Quarter was all but levelled. Where Spanish art objects, especially illuminated manuscripts survived, it was usually because Jews sent them to safer countries before or straight after 1492.

Thanks for the permission! I don’t have a ton of followers or anything, but there’s a big Jewish subculture on Tumblr so I know this entry will appeal to a lot of people.

Again, thanks for all the work you do on this blog. I can only imagine how much time it takes. I noticed that you’re closing in on your ten year anniversary – that’s an amazing achievement!

Oh wow, it’s less than a month away! I’ll have to post something celebratory. Thanks for the reminder. :thanks:

I, too, wish to thank you for gleaning from all that is out there and offering us this wonderful blog of history and archaeology..just mind-blowing, some of it. I share some of it on my Facebook page, with credit of course, as I know others will find this just as exciting as I do. Please keep on educating us about the past! :thanks:

I am trying to nurse my speranza back to life–but in the meantime, I would settle for another piece or two of that same bowl so that we can extrapolate a bit more of the composition and iconography. There is actually a surprising amount of Jewish imagery in museums and especially museum storage.

Why is someone using the name “livius drusus” in the blog? He lived ca. 124-91 B.C. Are you a relative?