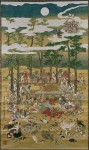

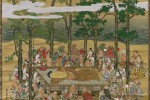

The depiction of the death of the Buddha surrounded by the inconsolable grief of beings, human and animal, who have yet to achieve enlightenment and the detachment from earthly desires, has a long, rich tradition in Asian art. Hanabusa Itchō’s version, painted in 1713 during the Edo period, is done in the animated, dynamic style characteristic of his work. He was known for his keen observation of daily life and for biting parodies, one of which got him exiled for 12 years when he chose the mistress of the shogun as a subject for satire. He returned to Edo in 1710 after the death of shogun he’d offended, and quickly picked up where he’d left off.

The depiction of the death of the Buddha surrounded by the inconsolable grief of beings, human and animal, who have yet to achieve enlightenment and the detachment from earthly desires, has a long, rich tradition in Asian art. Hanabusa Itchō’s version, painted in 1713 during the Edo period, is done in the animated, dynamic style characteristic of his work. He was known for his keen observation of daily life and for biting parodies, one of which got him exiled for 12 years when he chose the mistress of the shogun as a subject for satire. He returned to Edo in 1710 after the death of shogun he’d offended, and quickly picked up where he’d left off.

His The Death of Buddha was hugely famous during the Edo period. It belonged to a Zen temple in Tokyo which is believed to have displayed it once a year during Nehan-e (Nirvana Day), the Buddhist holiday celebrating the death of the Buddha and his passing into Mahaparinirvana, for more than 150 years. Pilgrims traveled to the temple just to see the painted scroll as viewing it was believed to be good karma.

His The Death of Buddha was hugely famous during the Edo period. It belonged to a Zen temple in Tokyo which is believed to have displayed it once a year during Nehan-e (Nirvana Day), the Buddhist holiday celebrating the death of the Buddha and his passing into Mahaparinirvana, for more than 150 years. Pilgrims traveled to the temple just to see the painted scroll as viewing it was believed to be good karma.

The ownership history has a gap between 1850 and 1886. At some point before the latter date, it was acquired by Ernest Fenollosa, an American professor at Tokyo Imperial University who was an avid art historian and collector of Japanese art. In 1886, he sold his entire collection to Boston doctor Charles Goddard Weld (former Massachusetts governor William Weld is a scion of the family) conditional on its eventually going to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston where Fenollosa had attended art school. Weld bequeathed it to the MFA Boston after his death in 1911.

The ownership history has a gap between 1850 and 1886. At some point before the latter date, it was acquired by Ernest Fenollosa, an American professor at Tokyo Imperial University who was an avid art historian and collector of Japanese art. In 1886, he sold his entire collection to Boston doctor Charles Goddard Weld (former Massachusetts governor William Weld is a scion of the family) conditional on its eventually going to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston where Fenollosa had attended art school. Weld bequeathed it to the MFA Boston after his death in 1911.

The scroll hasn’t been on view since 1990 for its own protection. A massive piece at six feet wide and 10 feet tall, it’s the largest scroll in the museum collection and conservation for such a large, delicate piece is extremely challenging. Adding to the logistically difficulties, the scroll hasn’t been remounted since 1850 when it was still at the Zen temple in Tokyo. Because scrolls have unique pressures — they’re rolled, mounts regularly fail or being to tug, tear and pull at the painting — they’re usually remounted every century or so.

The scroll hasn’t been on view since 1990 for its own protection. A massive piece at six feet wide and 10 feet tall, it’s the largest scroll in the museum collection and conservation for such a large, delicate piece is extremely challenging. Adding to the logistically difficulties, the scroll hasn’t been remounted since 1850 when it was still at the Zen temple in Tokyo. Because scrolls have unique pressures — they’re rolled, mounts regularly fail or being to tug, tear and pull at the painting — they’re usually remounted every century or so.

The museum began planning the complex conservation of The Death of Buddha three years ago. Active conservation began in the spring of this year in the MFA Boston laboratory. Four conservators, two from the MFA Boston and two from the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery which has an exceptional collection of Asian art and is currently being renovated allowing East Asian painting experts Andrew Hare and Jiro Ueda to join in the conservation of one the great scroll paintings of the Edo period. It is truly a conservation dream team. Three of the four, lead conservator Philip Meredith and both of the Freer experts, did the traditional ten-year apprenticeships at registered conservation studios required by Japanese government regulation for the conservation of Japan’s cultural patrimony. Meredith was only the second westerner to complete the decade-long apprenticeship.

The museum began planning the complex conservation of The Death of Buddha three years ago. Active conservation began in the spring of this year in the MFA Boston laboratory. Four conservators, two from the MFA Boston and two from the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery which has an exceptional collection of Asian art and is currently being renovated allowing East Asian painting experts Andrew Hare and Jiro Ueda to join in the conservation of one the great scroll paintings of the Edo period. It is truly a conservation dream team. Three of the four, lead conservator Philip Meredith and both of the Freer experts, did the traditional ten-year apprenticeships at registered conservation studios required by Japanese government regulation for the conservation of Japan’s cultural patrimony. Meredith was only the second westerner to complete the decade-long apprenticeship.

In August, the scroll and conservation team moved to the Asian Painting Gallery to give the public the rare opportunity to watch the painstaking work in progress in an exhibition called Conservation in Action: Preserving Nirvana. The scroll had to be dismantled from mount screws to linings to silk borders. After cleaning, consolidation, crease flattening, removal of old linings, replacement with new linings and the reassembling of every part, the scroll must be stretch dried on a custom karibari drying board 18 feet long.

It’s in the home stretch now, but conservation still proceeds apace. Visitors to the MFA Boston galleries can view the team at work until January 16th, 2017. The rest of us can get a glimpse into this extraordinary labor of love and expertise in the following videos.

A fascinating overview of the conservation process:

[youtube=https://youtu.be/pHfv1Jz0OXc&w=430]

Timelapse video of the conservation team applied temporary facing to the painting:

Here the team applies layers of protective paper, humidifying the work and removing the temporary facing. Then they turn it face down and remove old linings from the creases so that they can brush out the creases and re-flatten the painting.

In this last timelapse video, the conservators remove all the old lining paper from the back of the painting, lifting it with bamboo sticks and tweezing off the fibers that remain. They replace the old lining with fresh Mino washi, a traditional Japanese mulberry paper that is on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, adhered with wheat starch paste.

My favorite is the elephant!