According to Livy’s account of early Roman history in Ab Urbe Condita, the first iteration of the Circus Maximus was built in the valley between the Palatine and Aventine hills by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the legendary fifth king of Rome, in the 6th century B.C.

According to Livy’s account of early Roman history in Ab Urbe Condita, the first iteration of the Circus Maximus was built in the valley between the Palatine and Aventine hills by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, the legendary fifth king of Rome, in the 6th century B.C.

Then for the first time a space was marked for what is now the “Circus Maximus.” Spots were allotted to the patricians and knights where they could each build for themselves stands – called “ford” – from which to view the Games. These stands were raised on wooden props, branching out at the top, twelve feet high. The contests were horse-racing and boxing, the horses and boxers mostly brought from Etruria. They were at first celebrated on occasions of especial solemnity; subsequently they became an annual fixture, and were called indifferently the “Roman” or the “Great Games.”

There’s no archaeological evidence for this (or for much of an anything else to do with the putative kings of Rome, for that matter). The low-lying area would have been subject to regular flooding and was probably farmland. A drainage system would have made it possible for the field to be used for horse races, but the wooden stands were temporary and rebuilt many times. Permanent wooden seating was built in 329 B.C.; the first stone seating (for senators, of course) was built in the 190s B.C.

It was Julius Caesar’s ambitious building program that developed the Circus Maximus into something more akin to our image of it. He built stands on both sides down the full length of the track, with the trackside seating reserved for senators. Equites (knights) got the next rows and the plebs got the nosebleed seats. There were shops under the galleries where sports fans could get a bite or place a bet. It was all still wood, though, and was seriously damaged by fire in 31 B.C. and the great conflagration of 64 A.D. during which Nero so notoriously strummed the lyre. The stone Circus Maximus as we know it now was built by Trajan in the first years of the 2nd century and commemorated on a bronze sestertius minted from 103 to 111 A.D. At its largest, it was 600 yards long and 140 yards wide and could seat a quarter of a million people.

It was Julius Caesar’s ambitious building program that developed the Circus Maximus into something more akin to our image of it. He built stands on both sides down the full length of the track, with the trackside seating reserved for senators. Equites (knights) got the next rows and the plebs got the nosebleed seats. There were shops under the galleries where sports fans could get a bite or place a bet. It was all still wood, though, and was seriously damaged by fire in 31 B.C. and the great conflagration of 64 A.D. during which Nero so notoriously strummed the lyre. The stone Circus Maximus as we know it now was built by Trajan in the first years of the 2nd century and commemorated on a bronze sestertius minted from 103 to 111 A.D. At its largest, it was 600 yards long and 140 yards wide and could seat a quarter of a million people.

When I lived in Rome in the 80s, the Circus Maximus was open, but there wasn’t much to see. You could picnic on the grassy slopes which once held stone and wood bleachers, go jogging, walk your dog. At night it was something of a shady place frequented by the demimonde, as it were. More recently it’s been a venue for concerts and other public events. It was basically a large oval field with some bits in the middle and at the ends. In 2009, the city initiated a program of excavation and restoration to create an archaeological park worthy of such a great icon of the Eternal City. While excavations will continue, the newly revived Circus Maximus is now open to visitors.

When I lived in Rome in the 80s, the Circus Maximus was open, but there wasn’t much to see. You could picnic on the grassy slopes which once held stone and wood bleachers, go jogging, walk your dog. At night it was something of a shady place frequented by the demimonde, as it were. More recently it’s been a venue for concerts and other public events. It was basically a large oval field with some bits in the middle and at the ends. In 2009, the city initiated a program of excavation and restoration to create an archaeological park worthy of such a great icon of the Eternal City. While excavations will continue, the newly revived Circus Maximus is now open to visitors.

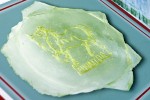

The excavation has uncovered many artifacts and structures long obscured by the overgrowth. Archaeologists have found more than 1,000 bronze coins, fragments of gold jewelry, and perhaps most excitingly, the bottom of a glass goblet with the image and name of a horse engraved in gold. Named after the legendary king of Alba Longa, descendant of Aeneas of Troy and grandfather of Romulus and Remus, Numitor the horse holds a golden palm branch in his mouth, attribute of the goddess Victory. This is the first time any kind of horse-related artifact has been found at the stadium which held chariot races for 1,000 years. The image of Numitor the lucky horse will be the new logo of the Circus Maximus.

The excavation has uncovered many artifacts and structures long obscured by the overgrowth. Archaeologists have found more than 1,000 bronze coins, fragments of gold jewelry, and perhaps most excitingly, the bottom of a glass goblet with the image and name of a horse engraved in gold. Named after the legendary king of Alba Longa, descendant of Aeneas of Troy and grandfather of Romulus and Remus, Numitor the horse holds a golden palm branch in his mouth, attribute of the goddess Victory. This is the first time any kind of horse-related artifact has been found at the stadium which held chariot races for 1,000 years. The image of Numitor the lucky horse will be the new logo of the Circus Maximus.

A wealth of architectural remains have been revealed on the Palatine end of the track. Visitors will now be able to walk two stories of galleries: the lower one that senators walked to reach their trackside seats and the upper one the plebs used to reach their bleachers. From there, they can walk along the paved road unearthed during the recent excavations which features a large water trough made of travertine slabs. They can see the latrines used by the same ancient audience members, and the shop fronts, brothels, money changers and betting parlors underneath the galleries.

A wealth of architectural remains have been revealed on the Palatine end of the track. Visitors will now be able to walk two stories of galleries: the lower one that senators walked to reach their trackside seats and the upper one the plebs used to reach their bleachers. From there, they can walk along the paved road unearthed during the recent excavations which features a large water trough made of travertine slabs. They can see the latrines used by the same ancient audience members, and the shop fronts, brothels, money changers and betting parlors underneath the galleries.

The Torre della Moletta, the 12th century tower built by the powerful Frangipani family as part of a fortification system that extended up the Palatine, has been restored and a new staircase added to the interior so visitors can climb to the top of the tower and enjoy a spectacular view of the Circus Maximus. In the hemicycle behind the tower, large marble fragments of the ancient structure discovered during the excavations have been tidily arranged in the grassy space: steps, cornices, column capitals, thresholds of shops, marble columns and the architectural elements of the triumphal arch of Titus discovered last year. Some of the bronze letters of the inscription dedicating the arch to Titus’ conquest of Judea — previously known only from a 9th century transcription — were found during the excavation, a wonderful surprise given how much ancient bronze was melted down in the Middle Ages.

The Torre della Moletta, the 12th century tower built by the powerful Frangipani family as part of a fortification system that extended up the Palatine, has been restored and a new staircase added to the interior so visitors can climb to the top of the tower and enjoy a spectacular view of the Circus Maximus. In the hemicycle behind the tower, large marble fragments of the ancient structure discovered during the excavations have been tidily arranged in the grassy space: steps, cornices, column capitals, thresholds of shops, marble columns and the architectural elements of the triumphal arch of Titus discovered last year. Some of the bronze letters of the inscription dedicating the arch to Titus’ conquest of Judea — previously known only from a 9th century transcription — were found during the excavation, a wonderful surprise given how much ancient bronze was melted down in the Middle Ages.

Archaeologists plan to continue excavations. They are hopeful that something of the ancient spina, the central strip that in its heyday boasted two Egyptian obelisks, an altar to the gods and the lap counters (first egg-shaped, later dolphins) so memorably portrayed on the screen in Ben Hur, might still slumber under the earth. Maybe the remnants of the original track or drainage system are down there 30 feet underground. Any discovery at all from the archaic era would be a massive archaeological bonanza.

The Circus Maximus will be open to tourists (tickets cost three to five euros) every day from now through December 11th. After that it will be open on weekends only, weekdays by appointment.

Oh, what a pity they have begun to dig there! It was such peaceful place to have a rest in after long hours of sightseeing. Hannu ;-))

So cool! Love articles about ancient Rome.

:boogie:

“Cypress and ivy, weed and wallflower grown

Matted and massed together—hillocks heaped

On what were chambers—arch crushed, column strown

In fragments—choked up vaults, and frescos steeped

In subterranean damps, where the owl peeped,

Deeming it midnight:—Temples—Baths—or Halls?

Pronounce who can: for all that Learning reaped

From her research hath been, that these are walls—

Behold the Imperial Mount! ’tis thus the Mighty falls…”