In 814 A.D., a hermit named Pelagius saw a single star of great brilliance and a shower of stars around it over the Libredón forest near Iria Flavia (modern-day Padrón), seat of the main bishopric in Galicia. Pelagius, other brother hermits and some shepherds approached the site and heard a choir of heavenly hosts singing. Bishop Theodomirus in Iria was told of this portent. He had the underbrush cleared to reveal an arch over an altar with a sarcophagus at its feet. Either from divine revelation or from a papyrus found in the sarcophagus, Theodomirus realized this was the tomb of St. James, son of Zebedee, brother of John and one of the Twelve Apostles. According to local legend, James, who was decapitated by Herod Agrippa in Jerusalem, had preached in what is now Spain and after his death his body was miraculously transported in a rudderless boat from Jaffa to Iria Flavia and thence inland for burial.

In 814 A.D., a hermit named Pelagius saw a single star of great brilliance and a shower of stars around it over the Libredón forest near Iria Flavia (modern-day Padrón), seat of the main bishopric in Galicia. Pelagius, other brother hermits and some shepherds approached the site and heard a choir of heavenly hosts singing. Bishop Theodomirus in Iria was told of this portent. He had the underbrush cleared to reveal an arch over an altar with a sarcophagus at its feet. Either from divine revelation or from a papyrus found in the sarcophagus, Theodomirus realized this was the tomb of St. James, son of Zebedee, brother of John and one of the Twelve Apostles. According to local legend, James, who was decapitated by Herod Agrippa in Jerusalem, had preached in what is now Spain and after his death his body was miraculously transported in a rudderless boat from Jaffa to Iria Flavia and thence inland for burial.

When the miraculous find was reported to King Alfonso II of Asturias and Galicia, he ordered a chapel built on the site, a modest structure of stone and mud. He added a baptistery, another church and a small monastery and built a defensive wall around the small settlement called Compostela (ostensibly a corruption of the Latin “campus stellae” or field of stars in reference to the miracle Pelagius had witnessed). The legend of St. James’ burial in Spain had spread widely in the 8th century, a cultural rallying cry against the Umayyad conquest of the Iberian peninsula, so the discovery of his relics made a huge splash. It was considered a divine sign that Iberia would be Christian again, that retaking it was a holy crusade. Alfonso notified Pope Leo III and Charlemagne of the find, and they spread the world all over Christendom. Pope Leo had lost Corsica and Sardinia to Muslim raiders from Al-Andalus in 809-810, so he was very much on board with the St. James messaging.

Soon the pilgrims were flocking in thousands to Santiago de Compostela, first from the peninsula and then from all over Europe. The Way of Saint James became the most important pilgrim destination after Rome and Jerusalem. Alfonso II’s humble chapel was replaced in 899 by a stone basilica ordered by King Alfonso III. Built in the Asturian style with three naves and a rectangular head, this church was razed to the ground a century later by Al-Mansur, defacto ruler of Al-Andalus when the Caliph Hisham was but a boy, although he made a point not to damage the holy tomb of St. James.

Soon the pilgrims were flocking in thousands to Santiago de Compostela, first from the peninsula and then from all over Europe. The Way of Saint James became the most important pilgrim destination after Rome and Jerusalem. Alfonso II’s humble chapel was replaced in 899 by a stone basilica ordered by King Alfonso III. Built in the Asturian style with three naves and a rectangular head, this church was razed to the ground a century later by Al-Mansur, defacto ruler of Al-Andalus when the Caliph Hisham was but a boy, although he made a point not to damage the holy tomb of St. James.

In 1075, Alfonso VI, King of Castile and Leon, began constructing a new church. This one was to be a grand Romanesque cathedral that could accommodate the huge numbers of pilgrims following the Way of St. James without disrupting the quotidian services of the church. The new church would have a round head for traffic flow, a gallery above the aisles for crowd management and side doors to allow pilgrims access to the crypt underneath the altar without having the stomp through the nave during regular worship.

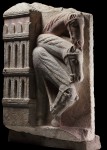

Construction stopped and started over the next century and in 1168, Master Mateo, an architect and sculptor of French origin, was engaged by King Ferdinand II of León to create a new main façade worthy of one of the holiest sites in Christendom. The old façade was demolished and in its place rose a massive two-story portico with three arches matching the three naves. Wide piers supported the arches and Mateo decorated them with an incredibly rich density of high relief sculptures. Around the base were fantastical animals. The middle of the piers featured pilasters with sculptures of the apostles and prophets. The sculptures at the top of the piers are symbols from the Old Testament and Book of Revelation. St. James gets central placement on the mullion of the central column, and at its foot facing in towards the altar instead of out at the pilgrims is Master Mateo himself, holding a sign identifying himself as the Architectus.

Construction stopped and started over the next century and in 1168, Master Mateo, an architect and sculptor of French origin, was engaged by King Ferdinand II of León to create a new main façade worthy of one of the holiest sites in Christendom. The old façade was demolished and in its place rose a massive two-story portico with three arches matching the three naves. Wide piers supported the arches and Mateo decorated them with an incredibly rich density of high relief sculptures. Around the base were fantastical animals. The middle of the piers featured pilasters with sculptures of the apostles and prophets. The sculptures at the top of the piers are symbols from the Old Testament and Book of Revelation. St. James gets central placement on the mullion of the central column, and at its foot facing in towards the altar instead of out at the pilgrims is Master Mateo himself, holding a sign identifying himself as the Architectus.

The overall theme was the salvation granted by God after the Final Judgment. Each of the three entrance arches represent different aspects of the theme. The left entrance focused on the Old Testament prophets, the right on punishments of the damned, the center of Christ the savior.

The overall theme was the salvation granted by God after the Final Judgment. Each of the three entrance arches represent different aspects of the theme. The left entrance focused on the Old Testament prophets, the right on punishments of the damned, the center of Christ the savior.

In the central tympanum Christ displays his wounds surrounded by the four Evangelists and their symbols. Angels carry the instruments of the passion — the cross, crown of thorns, nails and spear — while above them are a great throng of the blessed.

The 3D carving and individual detail of the more than 200 figures were great innovations in Romanesque art, and Master Mateo worked on his magnum opus, known as the Portico of Glory, until 1211. He and his workshop also created a sculpted stone choir which was replaced by a wooden one in the 17th century.

In the 16th century, the western façade of the Portico of Glory was taken down and the figures removed. Some were installed in other locations in the cathedral. Others went to museums or private collections. Because people are crazy, some of these precious sculptures were even treated like trash, used as fill in various construction projects at the cathedral. Thankfully the crazy abated and in the 18th century the Portico of Glory was encased by a new Baroque façade for its own protection. Exposure to the elements for 500 years had damaged the sculptures. They still managed to retain some of their polychrome painted elements, although most of the surviving color is from later restorations rather than the original.

In the 16th century, the western façade of the Portico of Glory was taken down and the figures removed. Some were installed in other locations in the cathedral. Others went to museums or private collections. Because people are crazy, some of these precious sculptures were even treated like trash, used as fill in various construction projects at the cathedral. Thankfully the crazy abated and in the 18th century the Portico of Glory was encased by a new Baroque façade for its own protection. Exposure to the elements for 500 years had damaged the sculptures. They still managed to retain some of their polychrome painted elements, although most of the surviving color is from later restorations rather than the original.

Work at the cathedral over the years has unearthed some of those discarded Master Mateo works. Now the Museo Nacional del Prado is exhibiting 14 sculptures from the Portico of Glory and the dismantled choir, some of them together again for the first time 500 years.

The present exhibition includes fourteen works, opening with the document in which Ferdinand II grants a lifetime pension to [Master] Mateo, a text that constitutes the first reference to his activities at the cathedral.

Horses from the Retinue of the Three Kings – reused as infill material for the Obradoiro staircase and recovered in 1978 still with traces of its original polychromy – and Saint Matthew came from the retro-choir and exterior façades, respectively, of the granite choir constructed by Mateo and his workshop around the year 1200.

The other works on display are from the lost west façade, including the sculptures of David and Solomon which, following the dismantling of that façade, were reinstalled on the parapet of the Obradoiro loggia where they remained until they were recently restored on site prior to their inclusion in this exhibition; and the Statue-column of a male figure with a cartouche, a damaged figure that was rediscovered this October inside the cathedral’s bell tower where it had been used as infill material and is now being presented to the public

for the first time. Also on display are other architectural elements that were part of the façade such as the large Rose window which crowned the central doorway and was reconstructed from fragments found in 1961; and two Keystones with the punishment of Lust, possibly from the arch on the south side, which had the same iconographic theme as the corresponding arch of the Portico of Glory, devoted to the Last Judgment.

A custom app created for the exhibit will allow visitors to virtually tour the Portico of Glory and the stone choir as Master Mateo designed them. The exhibition opened on November 28th and will run through March 26th, 2017.

At first, I was deeply ‘petrified’, a bit ‘rocked’ so to speak, about the Saint’s name. St. Jacobus’ place of worship in Spain is Santiago de Compostela for a reason, and not Santjames de Compostela, or similar 😮

——–

“The English name “James” comes from Italian “Giacomo”, a variant of “Giacobo” derived from Jacobus in Latin, itself from the Greek Ἰάκωβος. In French, Jacob is translated “Jacques”. In eastern Spain, Jacobus became “Jacome” or “Jaime”; in Catalonia, it became “Jaume”, in western Iberia it became “Iago”, from Hebrew יַעֲקֹב, which when prefixed with “Sant” became “Santiago” in Portugal and Galicia.”

Marvelous article! What with all the waxing and waning of crazy 👿 , it’s a miracle the cathedral hasn’t been damaged in any wars.

Can anybody help to identify this object?

sorry, couldn’t upload link

https://postimg.org/image/de8hjapff/

Hm..

Wish I had the opportunity to see the exhibition. Thanks for sharing!

This was a particularly interesting post, as my father’s family hails from Galicia; all “gallego” history and lore appeals to me.

a last supper, with the 12 apostles.

You need to provide more information. It might be a stolen European, rather simple medieval ‘wayside shrine’, maybe one of the (scriptural) ‘Stations of the Cross’, but those scriptural versions were inaugurated on Good Friday 1991. The ‘First’ station is: ‘Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane’. Therefore, it might be older than 1400, or younger than 1991 😀

—-

Then Jesus came with them to a place called Gethsemane, and he said to his disciples, “Sit here while I go over there and pray.” He took along Peter and the two sons of Zebedee [James and Jacob!], and began to feel sorrow and distress. Then he said to them, “My soul is sorrowful even to death. Remain here and keep watch with me.” He advanced a little and fell prostrate in prayer, saying, “My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me; yet, not as I will, but as you will.” When he returned to his disciples he found them asleep. He said to Peter, “So you could not keep watch with me for one hour? Watch and pray that you may not undergo the test. The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.”

Love the content on your article – very interesting!

Loved this article, would love to see you post more like this one