Last summer, De Vrije University asked that people who had made archaeological discoveries under the Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands (PAN) scheme report their finds to university researchers as part of a new study of such finds. One of the reports came from metal detectorist Mark Volleberg who in 2016 unearthed 23 Roman gold coins in an orchard in the village of Lienden on the outskirts of Buren in the central Dutch province of Gelderland. Metal detectorists Dik van Ommeren and Cees-Jan van de Pol reported that they had discovered eight gold coins in the same place in 2012 when the field was cleared to make way for the planting of the orchard.

Last summer, De Vrije University asked that people who had made archaeological discoveries under the Portable Antiquities of the Netherlands (PAN) scheme report their finds to university researchers as part of a new study of such finds. One of the reports came from metal detectorist Mark Volleberg who in 2016 unearthed 23 Roman gold coins in an orchard in the village of Lienden on the outskirts of Buren in the central Dutch province of Gelderland. Metal detectorists Dik van Ommeren and Cees-Jan van de Pol reported that they had discovered eight gold coins in the same place in 2012 when the field was cleared to make way for the planting of the orchard.

Researchers sought out more information about this exceptionally productive property. Archival research revealed that the field has been parturient (and you thought “ensorceled” was a good one) with Roman gold since the 19th century. At least twice in the 1840s gold coins had been found on the field in Lienden which then belonged to Baron van Brakell, and more were found in 1905 and 1916. While the whereabouts of the coins from the 19th century are no longer known, extant records mention three gold solidi of Valentinianus, three of Constantine, two of Honorius and one of Majorianus.

Not counting the long-lost ones that can’t be tracked down anymore, the study found a total of 42 pieces unearthed from the orchard site over the years. They are all solidi, a pure gold coin issued in the late Roman Empire, first by Constantine and then by subsequent emperors. The coins found in Leinden were minted over the course of more than 80 years. Most of them, 29 of the solidi, date to the late 4th, early 5th century: five of Valentinian II; 10 of Honorius; 13 of Constantine III and one of Jovinus. A group from the mid-5th century consists of eight solidi of Valentinian III, one of the usurper Johannes and the most recent of them all, a solidus of Majorianus.

Not counting the long-lost ones that can’t be tracked down anymore, the study found a total of 42 pieces unearthed from the orchard site over the years. They are all solidi, a pure gold coin issued in the late Roman Empire, first by Constantine and then by subsequent emperors. The coins found in Leinden were minted over the course of more than 80 years. Most of them, 29 of the solidi, date to the late 4th, early 5th century: five of Valentinian II; 10 of Honorius; 13 of Constantine III and one of Jovinus. A group from the mid-5th century consists of eight solidi of Valentinian III, one of the usurper Johannes and the most recent of them all, a solidus of Majorianus.

The variety of time periods and emperors is not unusual for late Roman solidus hoards. These coins were so valuable, they weren’t in common circulation. They were worth years of pay for most people, and were collected and hoarded for years, even generations. It’s almost certain that they were buried in a single hoard in the very last years of the Western Roman Empire.

These coins, scattered as they are in multiple finds over centuries, are of great historical significance. For one thing, taken all together, they constitute the largest solidus hoard ever found in the Netherlands. They also include the last known Roman coin tax from the Netherlands and environs: the one solidus minted by Emperor Majorianus (r. 457-461). Archaeologists believe the hoard was buried around 460 A.D., a mere 16 years before Odoacer deposed the last Roman Emperor Romulus Augustulus marking the conventional end date of the Western Empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

With the discovery of the 23 gold coins in 2016, Dik van Ommeren and Cees-Jan van de Pol, who up until then had kept their 2012 discovery of gold coins secret, alerted researchers to their 2012 finds. When the archives confirmed the field’s long history of producing Roman solidi,

archaeologists Stijn Heeren and Nico Roymans of the Free University and the National Service for Cultural Heritage determined that the site must be professionally excavated. It was a small excavation, just three trenches, and no new coins were unearthed. The team had also hoped to find remnants of a container — a pouch or box or jar or any other vessel used to hold the hoard when it was still intact — but there was no joy there either. The last item on the agenda was determining the larger context of the hoard. Was it buried in a house or settlement? Maybe a temple or in a grave? Mark Volleberg said he’d seen what looked like human bone fragments where he found the gold coins in 2016. He didn’t touch or disturb them, so archaeologists were hopeful they might be able to find those bones.

They did indeed discover human skeletal remains. Testing determined they belonged to four individuals, three inhumation burials and one cremation grave in an urn. Radiocarbon dating results dashed any hopes that they might be connected to the solidus hoard. The inhumation burials date to around 1800 B.C., the Middle Bronze Age, so way earlier than the coins. The cremains probably date to the Iron Age, but can’t be pinned down with any more precision.

They did indeed discover human skeletal remains. Testing determined they belonged to four individuals, three inhumation burials and one cremation grave in an urn. Radiocarbon dating results dashed any hopes that they might be connected to the solidus hoard. The inhumation burials date to around 1800 B.C., the Middle Bronze Age, so way earlier than the coins. The cremains probably date to the Iron Age, but can’t be pinned down with any more precision.

While the burials don’t appear to have a direct link to the hoard, archaeologists suspect the Middle Bronze Age tomb, perhaps on what was then a hill, was used in the 5th century as a handy place marker for the hoard. It would have been a recognizable spot on the landscape, the kind of place you’d pick to bury a treasure you had every intention to come back for when the coast was clear. The hill was likely flattened in the 1840s so it could be used as farmland. That’s when the coins started turning up.

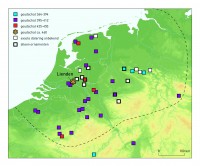

A notable number of late Roman gold coin hoards have been found in the Netherlands and Low Countries, 27 of them, to be precise, most of which date to the beginning of the 5th century. This timing is not a coincidence. Usurper Constantine III’s was fighting against Emperor Honorius while Germanic incursions crossed the Rhine into Gaul, inflicting a blow against the empire’s border defenses from which it never recovered. Desperate for aid from the Franks, who were powerful, centered in Germany and already had an established history of serving as mercenaries in the Roman army, Constantine and Honorius tried to buy them some Frankish troops. Because solidi were pure gold and not subject to the vagaries of debasement, when assorted Roman emperors, rebels and usurpers had cash transactions to make, they used solidi. This was an official payment from government to government. Roman officials would give the Frank leaders piles of gold coins and they would then distribute them as they saw fit.

The Lienden hoard doesn’t quite fit this pattern, however, because it was buried more than 50 years later than most of the other gold coin hoards. Until now, the hoard evidence suggested Rome’s last spate of interest in the Low Countries was the early 5th century, but the new discoveries suggest there was one last injection of Roman gold in the area during the reign of Emperor Majorianus. Archaeologists think the gold payoffs were likely sent by General Aegidius, Majorianus’ man in Gaul, who in the late 450s was desperate to get the Frankish kings to send him soldiers to help him fend off the increasingly successful Germanic invasions of Gaul.

The Lienden hoard doesn’t quite fit this pattern, however, because it was buried more than 50 years later than most of the other gold coin hoards. Until now, the hoard evidence suggested Rome’s last spate of interest in the Low Countries was the early 5th century, but the new discoveries suggest there was one last injection of Roman gold in the area during the reign of Emperor Majorianus. Archaeologists think the gold payoffs were likely sent by General Aegidius, Majorianus’ man in Gaul, who in the late 450s was desperate to get the Frankish kings to send him soldiers to help him fend off the increasingly successful Germanic invasions of Gaul.

It worked (for a while). With Frankish support, Majorianus and Aegidius reconquered much of Gaul, booting out the Visigoths and Burgundians. When his trusted general Ricimer betrayed and killed Majorianus in 461, Aegidius established his own independent kingdomlet in northern Gaul. Again the Franks were integral to his military success. Frankish leader Childeric and his men fought by Aegidius’ side against the Visigoths at the Battle of Orléans in 463, ensuring his victory. It was short-lived, as was Aegidius. He was poisoned in 464, leaving Childeric ideally positioned to found the Merovingian dynasty that would rule France for three centuries. It’s purely speculative, of course, but given the dates, it’s entirely within the realm of possibility that the Lienden solidi were payment dispensed by Childeric to one of his Frankish followers.

The modern finders of the gold coins and the landowner have given the solidi on permanent loan to the Museum Valkhof in Nijmegen, which contains the largest collection of Roman finds in the Netherlands, where they are now on display, together again for the first time in decades, maybe even centuries.

While Romans and Germanic warlords tried at first to appease the Huns, i.e. with money payments to their leaders in gold, they did nonetheless invade European heartlands, along the Danube and southern Germany, they passed Cologne and invaded, south of the Netherlands, northern Gaul. They were, however, temporarily defeated in the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (451).

Of course, there were no Swiss Bank Accounts available back then, and for some of those “siphoned off” coins, the Huns were at least a decade too early. Two chapters of ‘Decem Libri Historiarum’ of Gregory of Tours, however, recount a number of battles fought by Childeric I of the Franks, Aegidius, Count Paul, and one “Adovacrius” or “Odovacrius” (or “Odoacer”) around the 460’s.

——–

PS: In thousand years from now, people might be disappointed not to find gold hoards from what is today. All there will be left, unfortunately, would be electronics waste and obscure ‘sacred’ word documents as prints 😎

Amazing discovery, thanks for sharing!

I’m a big fan of earthy treasures that were left from our ancestors. Can you give more details about the metal detector that he used to find all solidi coins? Since they were all pure gold how deep they were buried?

Thanks!

😎

I saw an article about it in the local De Gelderlander on Tuesday, but they were not given much information about it until the Friday press conference. So you probably beat all other English sources.

“obscure ‘sacred’ word documents”

That brings to mind Walter Miller’s “A Canticle for Leibowitz.” The book relates how, after a nuclear holocaust, a group of monks devote themselves to honoring Leibowitz (a scientist martyred for trying to preserve scientific knowledge). The monks collect and transcribe the Leibowitz Memorabilia – everything from shopping lists to technical documents and circuit diagrams – none of which they can actually understand.

Hi i am the finder from the treadure in 2016.

Me an cees-jan user an xp deus Dirk van ommeren xp coinmaster.

Gr mark

Fantastic article, do you have any idea what metal detector was used? Just makes you wonder what is left beneath our feets. It’s all so exciting this is why I love metal detecting 🙂

Treasure hunting is what really makes my heart beats fast!Thank you for this fantastic article! I loved reading it!