Intaglios are gems, miniature designs intricately carved on gemstones, but the 17 acquired by the Getty Museum at auction two weeks ago are gems among gems. That’s why those 17 pieces, many of them not even an inch long, cost the Getty just shy of $8 million, $7,939,250, to be precise.

Intaglios are gems, miniature designs intricately carved on gemstones, but the 17 acquired by the Getty Museum at auction two weeks ago are gems among gems. That’s why those 17 pieces, many of them not even an inch long, cost the Getty just shy of $8 million, $7,939,250, to be precise.

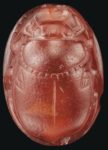

The entire sale of 40 Roman, Greek, Etruscan and Greco-Persian intaglio and cameo gemstones at Christie’s on April 29th raked in $10,640,500. Obviously the Getty with its bottomless pit of cash picked the choicest ones, but they weren’t the only players in this game because the hammer prices went far beyond pre-sale estimates. A Greek Mottled

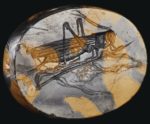

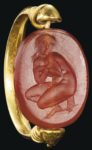

The entire sale of 40 Roman, Greek, Etruscan and Greco-Persian intaglio and cameo gemstones at Christie’s on April 29th raked in $10,640,500. Obviously the Getty with its bottomless pit of cash picked the choicest ones, but they weren’t the only players in this game because the hammer prices went far beyond pre-sale estimates. A Greek Mottled  Yellow Jasper Scaraboid with a Grasshopper from the Classical Period (ca. late 5th century B.C.), for example, was estimated to sell for $30,000-50,000. It sold for $519,000. A Roman Amethyst Ringstone with a Portrait of Demosthenes signed by Dioskourides, gem engraver to the Emperor Augustus, was estimated to sell for $200,000-300,000. The Getty dropped $1,575,000 on it.

Yellow Jasper Scaraboid with a Grasshopper from the Classical Period (ca. late 5th century B.C.), for example, was estimated to sell for $30,000-50,000. It sold for $519,000. A Roman Amethyst Ringstone with a Portrait of Demosthenes signed by Dioskourides, gem engraver to the Emperor Augustus, was estimated to sell for $200,000-300,000. The Getty dropped $1,575,000 on it.

The tradition of ancient carved gems was born from the seals and cylinders of Mesopotamia 5,000 years ago. They were sigils, used to make imprints into wet clay to sign official documents. From there they spread throughout Greece, Egypt and Persia and the Levant.

The tradition of ancient carved gems was born from the seals and cylinders of Mesopotamia 5,000 years ago. They were sigils, used to make imprints into wet clay to sign official documents. From there they spread throughout Greece, Egypt and Persia and the Levant.  Over the centuries they came to hold religious significance as well, carved with images of deities and mythological heroes, worn as amulets and consecrated to temples as votive offerings.

Over the centuries they came to hold religious significance as well, carved with images of deities and mythological heroes, worn as amulets and consecrated to temples as votive offerings.

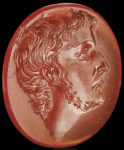

In the Greek Classical Period, the engraving became finer wrought and more detailed. The quality and variety of available stones took a great leap forward during the 3rd century B.C. thanks to Alexander the Great’s conquests. (You’d think, therefore, that there would be more than one gemstone carved with a bust of Alexander, but only one is known to survive

In the Greek Classical Period, the engraving became finer wrought and more detailed. The quality and variety of available stones took a great leap forward during the 3rd century B.C. thanks to Alexander the Great’s conquests. (You’d think, therefore, that there would be more than one gemstone carved with a bust of Alexander, but only one is known to survive .) While still used to create impressions, carved gemstones became primarily fashionable adornments at this time, jewels of high craftsmanship and expensive materials.

.) While still used to create impressions, carved gemstones became primarily fashionable adornments at this time, jewels of high craftsmanship and expensive materials.

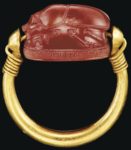

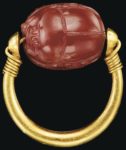

Intaglios, in which the designs are cut into the surface of a stone, are the direct descendants of the signet tradition.  The other form of ancient gem engraving, cameo, is its positive, a relief created by carving away the stone around it, the stone version of the clay bullae stamped from seals. Most of them were mounted onto rings in settings of precious metals. Larger pieces were used as pendants or perhaps brooches.

The other form of ancient gem engraving, cameo, is its positive, a relief created by carving away the stone around it, the stone version of the clay bullae stamped from seals. Most of them were mounted onto rings in settings of precious metals. Larger pieces were used as pendants or perhaps brooches.

Romans continued the Hellenistic tradition of carved gemstones, introducing a new material: glass, from which cameos could be cut with advanced knowledge of what layers of color would emerge, unlike the beautiful crapshoot of carving agates and chalcedonies.

Romans continued the Hellenistic tradition of carved gemstones, introducing a new material: glass, from which cameos could be cut with advanced knowledge of what layers of color would emerge, unlike the beautiful crapshoot of carving agates and chalcedonies.

The craft declined and fell along with the empire, but the  beauty of the stones ensured they were prized whenever they were discovered. In the Middle Ages they were mounted on religious objects, an inadvertent return to one of their more ancient functions. The revival of Classical art in the Renaissance drove a new interest in ancient intaglios and cameos. The wealthy collected them, sometimes remounting them into new pieces of jewelry. Come the Grand Tour in the 17th century, portable, glamorous engraved gemstones became de rigeur features of the most elegant and aristocratic cabinets of curiosities.

beauty of the stones ensured they were prized whenever they were discovered. In the Middle Ages they were mounted on religious objects, an inadvertent return to one of their more ancient functions. The revival of Classical art in the Renaissance drove a new interest in ancient intaglios and cameos. The wealthy collected them, sometimes remounting them into new pieces of jewelry. Come the Grand Tour in the 17th century, portable, glamorous engraved gemstones became de rigeur features of the most elegant and aristocratic cabinets of curiosities.

As an art dealer to European royalty and English Grand Tourist aristocrats, Count Antonio Maria Zanetti, amassed a great collection of carved gemstones, ancient and modern, and published a thorough catalogue of his pieces. His most beloved stone was a portrait of Antinous. Mirroring Hadrian’s fiery affection for his favorite, Zanetti pursued this one black chalcedony intaglio with unmatched passion. For 23 years he tried to get his hands on it. He said he

As an art dealer to European royalty and English Grand Tourist aristocrats, Count Antonio Maria Zanetti, amassed a great collection of carved gemstones, ancient and modern, and published a thorough catalogue of his pieces. His most beloved stone was a portrait of Antinous. Mirroring Hadrian’s fiery affection for his favorite, Zanetti pursued this one black chalcedony intaglio with unmatched passion. For 23 years he tried to get his hands on it. He said he  would have sold his house to buy it. By 1740, he had succeeded (and kept his house). He sold it shortly before his death in 1767 to George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough, who assembled a great collection of 780 engraved gemstones during his lifetime.

would have sold his house to buy it. By 1740, he had succeeded (and kept his house). He sold it shortly before his death in 1767 to George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough, who assembled a great collection of 780 engraved gemstones during his lifetime.

In this century, Roman art dealer Giorgio Sangiorgi acquired some of the finest ancient carved gemstones known, including the Marlborough Antinous. He carefully curated his collection, selecting exceptional examples from earlier dispersed collections like George Spencer’s. Most of them he bought before World War II, and while the collection has been in Switzerland since the late 1930s, has never been on public view and wasn’t published until last year, the ownership history of every gem is beyond impeccable, stretching back centuries.

In this century, Roman art dealer Giorgio Sangiorgi acquired some of the finest ancient carved gemstones known, including the Marlborough Antinous. He carefully curated his collection, selecting exceptional examples from earlier dispersed collections like George Spencer’s. Most of them he bought before World War II, and while the collection has been in Switzerland since the late 1930s, has never been on public view and wasn’t published until last year, the ownership history of every gem is beyond impeccable, stretching back centuries.

Little wonder the Getty jumped on these tiny masterpieces to the tune of eight million dollars.

“The acquisition of these gems brings into the Getty’s collection some of the greatest and most famous of all classical gems, most notably the portraits of Antinous and Demosthenes,” explains Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “But the group also

includes many lesser-known works of exceptional skill and beauty that together raise the status of our collection to a new level. Two such are the image of three swans on a Bronze Age seal from Crete, which has an elegance and charm transcending its early date (c. 1600 B.C.); and the image of the semi-divine Perseus, a marvel of minute naturalism that cannot fail to enthrall. This acquisition represents the most important enhancement to the Getty Villa’s collection in over a decade.”

Thank You! These are amazing.

“…Sir, in case you really have ‘APLU’ Claypay™, turn your scarab now and sign on the sodded line…”

:hattip:

————————-

I like those Minoan birds and wanted to know, where on the island they were found. This grasshopper I found relaxing on my sunbed in southern Crete (the rock in the background is the Νησίδες Παξιμάδια, ca. 20km off shore in the Lybian Sea, near to here).

The “[Δι]οσκουρίδου” (‘by Dioskourides’) on the ring is mirror-inverted: Although I could not tell what makes the depicted bearded man a “Demosthenes”, the inscription was made to be identifiable, when printed into clay or wax (as a “gimmick” or for actual use). When inverting and mirroring the picture [possibly again?], at closer inspection, even the “Δι” becomes a bit more readable.

Note that yet another “Διοσκουρίδης” had been a nephew of Antigonus I Monophthalmus (“Antigonos I, the One-Eyed”) and an admiral during the Wars of the Diadochi in the 4th century BC. Why would Augustus print “by Dioskourides” onto a seal in Greek? If he really did so, it may have been a ‘status symbol’, but did Augustus really need one? 😉