The Art Institute of Chicago’s most popular draw, Marc Chagall’s America Windows, will soon have a worthy companion in a monumental stained glass window by Tiffany Studios. It was purchased from the Community Church in Providence, Rhode Island, in June 2018, when its 48 layered-glass panels were painstakingly removed and transported to Chicago where it has been undergoing restoration.

The Art Institute of Chicago’s most popular draw, Marc Chagall’s America Windows, will soon have a worthy companion in a monumental stained glass window by Tiffany Studios. It was purchased from the Community Church in Providence, Rhode Island, in June 2018, when its 48 layered-glass panels were painstakingly removed and transported to Chicago where it has been undergoing restoration.

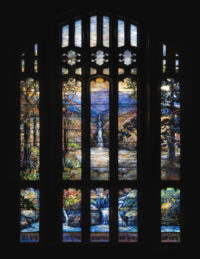

The window is 23 feet high and 16 feet wide, one of the largest windows ever made by Tiffany. It is attributed to Agnes F. Northrop, Tiffany’s premier master of landscape and floral designs. It depicts a landscape of waterfall, pool and forest with Mt. Chocorua, one of the White Mountains’ most frequently painted vistas, in the background. An inscription across the lower lancets reads: My help / cometh from / the Lord who / made heaven / and earth. On the bottom right is the signature: Tiffany Studios / New York 1917.

It was commissioned by Mary L. Hartwell as a memorial to her late husband fire extinguishing sprinkler magnate Frederick W. Hartwell who had died in 1911. Frederick Hartwell was born in New Hampshire and had lived there until he was 11 when he moved in with his uncle in Providence. The window nods to Mr. Hartwell’s birth state in its depiction of the White Mountains scene.

It was commissioned by Mary L. Hartwell as a memorial to her late husband fire extinguishing sprinkler magnate Frederick W. Hartwell who had died in 1911. Frederick Hartwell was born in New Hampshire and had lived there until he was 11 when he moved in with his uncle in Providence. The window nods to Mr. Hartwell’s birth state in its depiction of the White Mountains scene.

Mr. Hartwell had been a devout congregant and a very generous financial supporter of the Central Baptist Church of Providence. Originally founded in 1807 as the Second Baptist Church of Providence, it had moved and changed names repeatedly over the years. In 1917 it moved again to a brand new building and Mary Hartwell commissioned what would become known as the “Hartwell Memorial Window (Light in Heaven and Earth),” in memory of Frederick.

If you’re wondering why any person or institution would tear such a precious and beautiful piece of their history from its very walls, the church’s current name says it all. The Community Church of Providence is a small multi-denominational congregation that is entirely dedicated to serving its community.

If you’re wondering why any person or institution would tear such a precious and beautiful piece of their history from its very walls, the church’s current name says it all. The Community Church of Providence is a small multi-denominational congregation that is entirely dedicated to serving its community.

Museum officials did not reveal the purchase price but said that price alone was not what determined who would buy the work. Leaders of the Community Church, in deciding to sell it, wanted it to go to a museum and they wanted to know the museum’s plan for care and display of the window, said Oehler.

“I really credit the church with this foresight and thinking about their role as stewards for the window,” she said. “They have a very community focused mission, and they’re not a museum, and they’re not in the business of protecting works of art.”

In the news release announcing the acquisition, Pastor Evan Howard of the church said, “We are extremely pleased that this exceptional work of art has entered such a renowned collection.”

In picking AIC as “the ideal institution to care for and display the window,” Howard said the church hopes that it will be “experienced by a broad public audience that includes scholars, artists and visitors from around the world.”

They sure know their monumental stained glass, too, what with the five-year restoration of the Chagall windows.

Conservation is expected to be complete in the fall of this year. So far the window has been cleaned, one third of the panels removed for glass repair with more minor repairs performed on the panels in situ. The restored window will be installed at the top of the Grand Staircase by the Michigan Avenue entrance. It will be framed and backlit to stun and amaze all who enter there.

Conservation is expected to be complete in the fall of this year. So far the window has been cleaned, one third of the panels removed for glass repair with more minor repairs performed on the panels in situ. The restored window will be installed at the top of the Grand Staircase by the Michigan Avenue entrance. It will be framed and backlit to stun and amaze all who enter there.

Well done. For anyone interested in modern monumental stained glass:

“Dream Garden”

At the Curtis Building, 601 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 19106, United States

Designed by Louis C. Tiffany and based on a Maxfield Parrish landscape, it took 6 months to install in 1916. The mural is 15 feet by 49 feet made up of 100,00 pieces of glass in over 260 color tones making it arguably the largest Tiffany piece in the world (though the Tiffany art glass dome located in Preston Bradley Hall in the Chicago Cultural center certainly has a claim.) Dream Garden was the largest glass mural in the country until 2007 when it was surpassed by the Wing Lung Bank Mural in Alhambra, CA.

Though there was an attempt to sell the mural for 9 million dollars to a casino owner in the late 1990s, Philadelphia designated the mural a “historic object” putting a stop to the sale. Eventually, ownership of the mural was handed over to be jointly shared by four Philadelphia cultural institutions.

At first I read it as 48-layered panels, and thought yeah, right.

The I reread it to be 48 layered-glass panels…ok, of course, it IS Tiffany.

But I am unsure how you get 48 panels.

Congratulations! As a great-grandson of Elisha Hunt Rhodes, who served as Chairman of the Building Committee of the church until 1917, I feel confident that he would have been pleased with this outcome. As a devout Christian I think that he would support using the sale to further the mission of the church in welcoming the diverse congregation and its mission of feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, caring for the health and education of the needy. He admired Chicago in his visits there in the 19th century and would be pleased that this beautiful and meaningful window will be viewed by a larger audience. May it bring faith and peace to all who view it.

“If you’re wondering why any person or institution would tear such a precious and beautiful piece of their history from its very walls, the church’s current name says it all. The Community Church of Providence is a small multi-denominational congregation that is entirely dedicated to serving its community.”

Let me see if I understand this. The Community Church of Providence is “entirely dedicated to serving its community” by removing an inspiring work of art from the church building so its community can’t see it without traveling from Providence to Chicago.

Mr. Rhodes: “I feel confident that [Elisha Hunt Rhodes] would have been pleased with this outcome. As a devout Christian I think that he would support using the sale to further the mission of the church in welcoming the diverse congregation and its mission of feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, caring for the health and education of the needy.”

Aha! The Great God Diversity rules! Some of the diverse congregants are not Christian so (it is assumed) a gorgeous stained-glass window with a Christian theme might give them a heart attack.

Plus, the church’s mission of feeding the hungry, etc. must take absolute precedence over feeding the soul with beauty. Perish the thought that the Community Church might respect the importance of both.

I guess it’s just as well that the Tiffany Studio’s magnificent creation will be removed from a philistine, provincial church and placed on view in a museum that realizes its value.

I was asked by an art curator to write up an interpretation of this work of Tiffany, she she had read of my essay on the stained glass artist, John LaFarge. So I wrote this interpretation, called “Help From the Mountain.” See here below. David Cave, Cincinnati, Ohio

********

Help from the Mountain

In the mid-1800s a von Tramp-like family singing group from New Hampshire, called the Hutchinson Family Singers, “of a nest of brothers and a sister” (John, Asa, Judson, and Abby), were the most popular entertainers in America. They traveled the country singing in four-part harmony of their origins and itinerant lifestyle and as unabashed crusaders against the injustice of slavery and for social reform.

Their signature song, for which they were best known, interwove family lore with condemnations against inequality and intemperance, but also referenced allusions to nature and to regional and national pride. Titled “The Old Granite State” it had these lines: “We have come from the mountains, we have come from the mountains, we have come from the mountains, of the ‘Old Granite State’.” They’d sing “Liberty is our motto,” “equal liberty is our motto,” “we despise oppression,” we are “friends of emancipation,” and “we are all teetotalers.”

From the mountains of New Hampshire (the Granite State), The Hutchinson Family Singers brought moral uplift and the beauty of song to a troubled but promising nation. Though a religious family (firstly of the Congregational Church but then they became Baptists), their message reached the ears of the religious and of the non-religious, as they sung of hope and restoration, of pride of place, of family, and of salvation, as if coming down from heaven, to churches and to secular and political rallies alike.

That they would sing of coming from the mountains of New Hampshire they could just as well have included, among these mountains, the Mountain of Chocorua, depicted here in Agnes Northrup’s nourishing, serene landscape and in the magical beauty of Tiffany’s opalescent and mixed-media glass. Moreover, that they would come to lift the country upward through jubilant song and bring it together through their message and vocal harmony, they connect to the biblical inscription at the base of the landscape: “My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth,” which is the second verse that answers the opening verse and rhetorical question “I lift my eyes to the Mountain — from where will my help come? (Psalm 121:1,2).

This Northrup-Tiffany window is an important and multi-messaged work of art not simply because it is one of the few landscape stained glass windows fabricated by Tiffany and is a Agnes Northrup masterpiece. It is also important for what it captures and suggests, for what it reveals and conceals.

America of the 19th and early 20th century was a nation going through enormous change, of rapid urbanization, industrialization, and migration, with accompanying inequalities and ills, as the nation moved out of the vestiges of a civil war and into rapid growth and untold wealth. In this period American landscape painters naturally turned to the expansiveness, majesty, strength, nourishment, and purity of nature, seeing in it a leveling of all creatures, the intrinsic quality of all species, the characteristics of democracy, and of the virtues and divine blessing of America, of its own natural gifts, bestowing local, regional, and national pride. It is to this view of America that the Hutchinson Family Singers sang and that the Agnes Northrup and Louis Tiffany window caught in vivid, American-invented opalescent glass for church sanctuaries across the country, offering a religious sensibility that was not so much confessional as primordially spiritual.

So while the Northrup-Tiffany window reveals the grandiosity of American’s nature and of New Hampshire’s in particular, and suggests a calming assurance, its picture of Chocorua Mountain, of woods partially referenced at the margins, and with its inscription from Psalm 121, it also conceals troubled times and potential dangers. The legend of Chocorua recounts a story of mistrust and tragedy between Native Americans and settlers. The woods themselves, flanking the calming waters, hide the unknown, possible dangers, and the still unchartered and tamed wilds. And the scriptural inscription, it, too, conceals, for this psalm was written at a time when the nation of Israel had been exiled and displaced and scattered from its homeland in Palestine. The Psalmist, therefore, in a time of trial and longing for strength and protection looks to the “Mountain,” to the abode of God, for help.

One does not know if Northrup and Tiffany were aware of the legend of Chocorua, or meant to have the woods to intimate the harsher side of the bucolic and sylvan landscape, or if they knew of the historical context of the Psalm. While these elements are there, the purpose of the window for the patrons and for the worshipers in the sanctuary, was not to bring the perils of the world inside, but to offer up another vision of the world outside, a more hopeful one, a vision of tranquility, of unity, of equanimity, of peace, of hope and redemption, a vision that if we would just look to the mountain and welcome the help that comes from it, be it divine or human, we as a people, as a nation, will be uplifted and restored to that which we should become.

David Cave

April 3, 2017