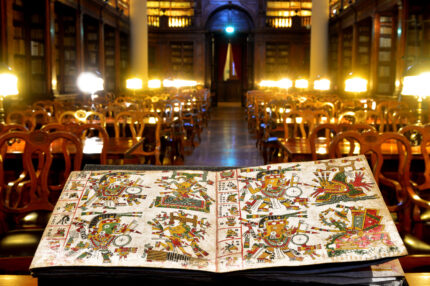

A brilliantly illustrated pre-Columbian divinatory manuscript at Bologna University Library is being analyzed with the latest imaging techniques to learn more about the composition and use of its paints, still brightly colored today.

“We will employ fluorescence and hyperspectral imaging techniques to map the distribution of compositional material (both organic and inorganic) on every page of the manuscript”, says Davide Domenici, Professor at the University of Bologna and head of the project. “The level of detail these techniques are able to provide is unprecedented and will shed new light on the pictorial and technological practices developed by pre-Columbian artists”. […]

The research team will employ a macro-XRF scanner. This tool uses X-rays to examine the elemental composition of the object under investigation. Once the distribution of chemical elements is known, it will be possible to identify the pigments composing those elements. In this way, researchers will be able to retrieve the distribution of orpiment (a deep-yellow mineral pigment) by looking for arsenic which is the element composing this pigment.

The Codex Cospi will also get through hyperspectral imaging in the visible range. This method allows to study how visible light is absorbed, reflected, and emitted. Some chemical compounds may present peculiar light absorption, reflection, emission, and hyperspectral imaging that can map their distribution. In particular, through hyperspectral imaging researchers can map the use of organic dyes such as indigo, which was used together with specific clays in the production of the famous Maya Blue.

One of only a dozen pre-Columbian texts to survive the veritable orgy of destruction inflicted on indigenous literature by the Spanish conquerors and their missionary zealots, the Codex Cospi is believed to have been illuminated at the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century. It has been in Bologna since the 1530s, brought there by Domingo de Betanzos, a Dominican missionary who administered a large territory in what is today Mexico for the Spanish crown. The former hermit went to Mexico in 1526 where he founded the Dominican Order in New Spain and carved out an independent province under the complete control of the order. He dispatched a few evangelizing missions, but he spent most of time on temporal matters and fighting with other clerical potentates over who controlled what. He never dealt directly with the indigenous people he wanted to forcibly convert, but took time from his busy schedule to insist that they could never be priests because they were less than rational humans. He wasn’t even sure they could be baptized, which would seem to be a rather glaring contradiction but there you have it.

One of only a dozen pre-Columbian texts to survive the veritable orgy of destruction inflicted on indigenous literature by the Spanish conquerors and their missionary zealots, the Codex Cospi is believed to have been illuminated at the end of the 15th or beginning of the 16th century. It has been in Bologna since the 1530s, brought there by Domingo de Betanzos, a Dominican missionary who administered a large territory in what is today Mexico for the Spanish crown. The former hermit went to Mexico in 1526 where he founded the Dominican Order in New Spain and carved out an independent province under the complete control of the order. He dispatched a few evangelizing missions, but he spent most of time on temporal matters and fighting with other clerical potentates over who controlled what. He never dealt directly with the indigenous people he wanted to forcibly convert, but took time from his busy schedule to insist that they could never be priests because they were less than rational humans. He wasn’t even sure they could be baptized, which would seem to be a rather glaring contradiction but there you have it.

The Nahuas’ alleged irrational animal natures didn’t prevent them from making a pretty enough book that Betanzos deemed it worthy to curry favor with Pope Clement VII when he met him in Bologna in 1533 to get more favorable terms for the Dominican province of Santiago de Mexico. The Pope was there to meet with Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who had sacked Rome and imprisoned Clement five years earlier. Betanzos came bearing splendid gifts: mantles with multi-colored parrot feathers so artfully woven into the cotton that it had the texture of velvet, turquoise mosaic ceremonial masks, a turquoise-handled knife, stone knives with edges sharp as razors and first and foremost, the Codex Cospi which Bolognese chronicler Leandro Alberti, described in 1548 as a book painted with figures “that looked like hieroglyphs by which they understand each other as we do by letters.”

The turquoise masks and knives are today part of the collection of the National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome. The Codex stayed put in Bologna. Its ownership history is hard to trace, but the likeliest trajectory is that the Pope didn’t take it to Rome with him and it ended up in the hands of Betanzos’ fellow Dominican Leandro Alberti. A handwritten inscription on the parchment cover of the manuscript records it having been gifted to Marchese Ferdinando Cospi in 1665. (They removed the original jaguar skin cover to replace it with the parchment at this time.) Cospi donated his vast cabinet of curiosities, codex included, to the city of Bologna in 1657. The manuscript was first held at the Academy of Science before ultimately it entered the collection of the Bologna University Library.

That is some amazing colour, I just wish I could understand what it shows…

It was a calendar, a roadmap for soothsayers, a pantheon of Gods/Goddesses and the appropriate offerings to each, a representation of Venus the Morning Star (Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli), a treatise on safeguards against dangerous jungle critters, hunting rituals, and perhaps advice on textile handicraft.

Encyclopedic. A Nahuatl Wikipedia perhaps? Made of deerskins. The colors are striking, particularly the ‘Maya Blue’ that strongly resists fading by time or by weather.

thanks mike, now where can I get my copy!