I didn’t know this until I read the paper, but the reason powdered mummies were considered a medicine in the Middle Ages was a misinterpretation of Arabic medical texts. Mumiyyah, the Arabic word for bitumen, was deemed curative for many illnesses in traditional Islamic medicine. It was used to heal wounds, broken bones and to treat stomach ailments, among other things. The best source of medical-grade bitumen was said to flow down from a mountain in Persia.

The 12th century Arabic text The Book of Simple Medicaments by Serapion the Younger included a description of bitumen’s many medical uses. When it was translated into Latin, the term mumiya was mistakenly identified as the black substance found inside mummies. That black stuff was described as a mixture of decomposition fluids mixed with embalming materials to create a sort of cadaver-generated version of the natural bitumen found in tar pits and flowing down mountains.

Interestingly enough, bitumen wasn’t part of the mummification process in ancient Egypt until the New Kingdom, and even then it wasn’t used all the time. It isn’t found consistently in Egyptian embalming until the Ptolemaic era (after 332 B.C.) when it was used along with resin and unguents in cavities left by the removal of organs. Physician, philosopher and prolific author Abd Al-Latif Al-Baghdadi wrote in his Account of Egypt in the 12th century that the mumiya found the cavities of preserved Egyptian bodies could substitute for the good stuff in a pinch. Latin medical books took that and ran with it so that by the time the game of telephone was over, entire mummies ground up into powder were deemed the equivalent of bitumen. A brisk trade in mummies ensued, as they were a lot cheaper to acquire than actual bitumen.

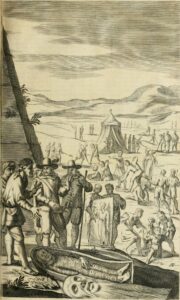

By the 16th century, Egyptian mummies were much in-demand among European scholars, medical professionals and curiosities collectors. Roman nobleman and musician Pietro Della Valle picked up a pair of mummies in 1615 during his voyage through Egypt on the way to the Holy Land. He visited the necropolis of Saqqara outside Cairo where looters dug up mummies by the gross to be pulverized for the insatiable materia medica market. When travelers were in town, they could pay to have mummies excavated in front of them or to explore the rock-cut chambers themselves for an added frisson. Della Valle got the deluxe tour package. He was climbed through tunnels into two pyramids in Cairo and walked through the maze of chambers. The next day he went to Saqqara, known to him as “the place where the mummies are,” and sought to buy a mummy souvenir from the peasants who ran active businesses looting the underground chambers of the necropolis.

By the 16th century, Egyptian mummies were much in-demand among European scholars, medical professionals and curiosities collectors. Roman nobleman and musician Pietro Della Valle picked up a pair of mummies in 1615 during his voyage through Egypt on the way to the Holy Land. He visited the necropolis of Saqqara outside Cairo where looters dug up mummies by the gross to be pulverized for the insatiable materia medica market. When travelers were in town, they could pay to have mummies excavated in front of them or to explore the rock-cut chambers themselves for an added frisson. Della Valle got the deluxe tour package. He was climbed through tunnels into two pyramids in Cairo and walked through the maze of chambers. The next day he went to Saqqara, known to him as “the place where the mummies are,” and sought to buy a mummy souvenir from the peasants who ran active businesses looting the underground chambers of the necropolis.

One of the looters lured him with the promise of a mummy of great beauty. It had been robbed from its grave three of four days earlier. It was intact, wrapped and covered by a full-length portrait painted on stuccoed linen. Della Valle described it in a letter published in his epistolary travelogue in 1650 as:

“excellently conserved and unusually adorned and composed which seemed to me to be something very beautiful and elegant. It depicted the man laid out, nude but tightly bandaged and wrapped in a large quantity of linen cloths, embalmed with that bitumen which, mixed with the flesh, is called Mumia and is given as a medicine. … There was also, on top the body, a cover made of linen cloth all painted and gilded that was very well stitched and sealed on all sides with lead seals. … [On it] was painted the effigy of a young man that without doubt is the portrait of the deceased, and was adorned in his clothing and from head to feet with so many painted and gold bagatelles, so many hieroglyphics and characters and similar fancies that believe me, it is the most gracious thing in the world.”

So enamored was he of the portrait mummy, Della Valle bought it on the spot and asked the seller if there was another. He said there was a second one just as beautiful still in the burial chamber. He and his associates quickly pulled it out of the pit and Della Valle was enchanted too see a second portrait mummy, this one of a young woman. He assumed it was the sister or wife of the young man buried in the chamber with her and the looters confirmed they’d been found next to each other. Again from the letter:

So enamored was he of the portrait mummy, Della Valle bought it on the spot and asked the seller if there was another. He said there was a second one just as beautiful still in the burial chamber. He and his associates quickly pulled it out of the pit and Della Valle was enchanted too see a second portrait mummy, this one of a young woman. He assumed it was the sister or wife of the young man buried in the chamber with her and the looters confirmed they’d been found next to each other. Again from the letter:

“The garment of the woman is much richer in gold and jewels than that of the man. In the gold plates spread over the surface, in additional to other signs and characters, are engraved certain birds and animals that look to me like lions, and in one of them in the lower middle, an ox or cow or what have you that is the symbol of Apis or Isis. In another, which dangles from the chest of the lowest necklace (because she has many necklaces), is the image of the Sun.”

He brought his prize mummies back to Rome with him in 1626. They were the first portrait mummies introduced to Europe. Pietro Della Valle’s collection was dispersed and sold after his death. In 1728, the pair of mummies were acquired for the collection of Friedrich August I, Elector of Saxony, aka King August II of Poland. Today August’s collection, mummies included, is part of the Dresden State Art Collections.

He brought his prize mummies back to Rome with him in 1626. They were the first portrait mummies introduced to Europe. Pietro Della Valle’s collection was dispersed and sold after his death. In 1728, the pair of mummies were acquired for the collection of Friedrich August I, Elector of Saxony, aka King August II of Poland. Today August’s collection, mummies included, is part of the Dresden State Art Collections.

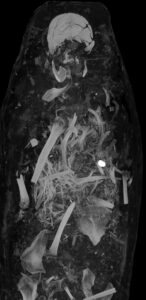

By some miracle, the Saqqara portrait mummies never suffered the destructive indignity of one those unwrapping parties that were so fashionable in the 19th century, nor was it destroyed by dissection. The two Dresden mummies and a third portrait mummy of a teenaged girl from the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo are the subjects of a new study that virtually unwraps them with a CT scanner.

The mummies were found to date to the late Roman period (3rd or 4th century A.D.). The man was between 25 and 30 years old when he died. He was about 5’4″ tall and had dental caries. His bones had been disturbed at some point, probably right after he was discovered. He does not seem to have been thoroughly mummified. There is no evidence of organ removal and few remains of embalming liquids. The brain was not removed from the woman’s mummy nor from that of the young girl. Researchers believe they were preserved largely by the use of natron as a desiccant.

The mummies were found to date to the late Roman period (3rd or 4th century A.D.). The man was between 25 and 30 years old when he died. He was about 5’4″ tall and had dental caries. His bones had been disturbed at some point, probably right after he was discovered. He does not seem to have been thoroughly mummified. There is no evidence of organ removal and few remains of embalming liquids. The brain was not removed from the woman’s mummy nor from that of the young girl. Researchers believe they were preserved largely by the use of natron as a desiccant.

The woman, who died between the ages of 30 and 40, stood about 4’11” (151 cm) tall. She had advanced arthritis in her left knee. The teenager,

who wore a hairpin, according to the CT scan, died between the ages of 17 and 19, and stood about 5’1″ (156 cm) tall. She had a benign tumor in her spine known as a vertebral hemangioma, which is more common in people over 40, the researchers said.

Both women were buried with multiple necklaces. It’s exciting to see these necklaces, but it’s not unexpected, [lead researcher Stephanie] Zesch said. “Because of these very precious shrouds, we are sure that those individuals have to be members of the higher socioeconomic class,” meaning that they could have easily afforded jewelry, Zesch said.

The study has been published in the journal PLOS One and be read in its entirety here.

The word εὐτυχί(α) (EYTYXI, “good luck” on the left coffin) may indicate that they must have reckoned with resurrection.

Indeed, the depictions in Fig 3. (1654, Athanasius Kircher) and Fig. 4. (1733, Raymond Leplat) from the journal PLOS One seem to be our mummies.

In contrast to my interpretation from yesterday (i.e. ΕΥTΥΧΙ=”Good luck”), the Greek inscription in the PLOS One article, referring to Johann J. Winckelmann (1717−1768), is there read as ΕΥΨΥΧΙ (Eupsychi) and translated as “Farewell”.

Maybe, the slight room for interpretation was left open intentionally. That rather fuzzy “cross” can be read as PSI or as TAU.

“His bones had been disturbed at some point” is a major understatement. It looks like someone had started the process of pulverization.

Well, Tristam, I suppose there is the chance that he was crushed by a falling slab while out pyramid building or whatever. Maybe we have a classic ‘locked coffin’ mystery?