A pottery jar containing chicken remains and engraved with the names of more than 55 curse targets has been discovered in the ancient Agora of Athens. Pierced with an iron nail and buried in a corner of the Classical Commercial Building around 300 B.C., the vessel was a class-action curse, an offering of dismembered chicken parts to the underworld deities to hobble the bodies and minds of dozens of named opponents.

A pottery jar containing chicken remains and engraved with the names of more than 55 curse targets has been discovered in the ancient Agora of Athens. Pierced with an iron nail and buried in a corner of the Classical Commercial Building around 300 B.C., the vessel was a class-action curse, an offering of dismembered chicken parts to the underworld deities to hobble the bodies and minds of dozens of named opponents.

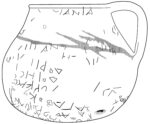

The jar, a rounded cooking pot known as a chytra, was unearthed in 2006 by archaeologists from the American School of Classical Studies at Athens but has only now been fully translated and published, revealing that the  simple unglazed pot was intended to be a weapon of mass destruction. The names of the curse victims were inscribed on the sides and bottom of the pot in two different hands. Today about 30 full names are legible; the rest have worn over the centuries and now survive only as a disconnected letter or lines. Inside were the remains of the head and lower legs of a chicken and one bronze coin.

simple unglazed pot was intended to be a weapon of mass destruction. The names of the curse victims were inscribed on the sides and bottom of the pot in two different hands. Today about 30 full names are legible; the rest have worn over the centuries and now survive only as a disconnected letter or lines. Inside were the remains of the head and lower legs of a chicken and one bronze coin.

The experts involved in the discovery believe that the nail and chicken parts together most likely played a role in the curse on the 55 different individuals. Nails, which are a common feature associated with ancient curses, “had an inhibiting force and symbolically immobilized or restrained the faculties of (the curse’s) victims,” [Yale Classics professor Jessica] Lamont stated in her scholarly article.

The archaeologists determined that the chicken that had been killed had been no older than seven months before it was slaughtered to be used as part of the ritual; they believe that the people who employed the magic may have wanted to transfer “the chick’s helplessness and inability to protect itself” to those they cursed by writing their names on the outside of the jar, Lamont stated.

She further explains that the head of the chicken, which had been twisted off, and its piercing, along its the lower legs, meant that the corresponding body parts in the 55 unfortunate people would also be similarly affected.

“By twisting off and piercing the head and lower legs of the chicken, the curse sought to incapacitate the use of those same body parts in their victims,” Lamont notes.

Lead curse tablets were the most common means to activate the power of chthonic deities against enemies in antiquity. Thirty of them were found in just one 4th century B.C. well in Athens. Curse jars are far more rare. Tablet or pot, the mechanism of most of these curses was the same: they were binding spells, intended to disable a rival’s physical and cognitive prowess. The target would be named, the curse articulated, a nail driven through the conveyance which would then be buried, often near a source of water, to put them in closer proximity to the underworld gods being invoked.

Lead curse tablets were the most common means to activate the power of chthonic deities against enemies in antiquity. Thirty of them were found in just one 4th century B.C. well in Athens. Curse jars are far more rare. Tablet or pot, the mechanism of most of these curses was the same: they were binding spells, intended to disable a rival’s physical and cognitive prowess. The target would be named, the curse articulated, a nail driven through the conveyance which would then be buried, often near a source of water, to put them in closer proximity to the underworld gods being invoked.

The use of a pot in this case is extremely unusual, and may be directly connected to the beef. With so many names on the curse list, it’s likely the conflict was over a court case. Legal disputes were the subject of many of the Athenian curse tablets, and everyone involved, from litigants to lawyers to judges to witnesses, were often targeted for binding spells. Given the jar’s burial in a commercial building known to have been used by potters, it’s possible the vessel was used rather than a more traditional lead tablet to inhibit participants in a potter-related lawsuit.

The use of a pot in this case is extremely unusual, and may be directly connected to the beef. With so many names on the curse list, it’s likely the conflict was over a court case. Legal disputes were the subject of many of the Athenian curse tablets, and everyone involved, from litigants to lawyers to judges to witnesses, were often targeted for binding spells. Given the jar’s burial in a commercial building known to have been used by potters, it’s possible the vessel was used rather than a more traditional lead tablet to inhibit participants in a potter-related lawsuit.

More or less “commercial” buildings do make sense near the Agora: Curse jars have to be handed in by market participants, and the council then usually decides within 28 days, if it is a “priority case”.

The word for ‘chicken’ –i.e. ἀλεκτοριδεύς– in Ancient Greek, however, looks rather funny, when taking into consideration that “λεκτός” (lectos) means “picked out” or “chosen”, so to speak, to get as a bird “elected for casserole”.

“ἄλεκτος” (“alektos”) means “not to be told, indescribable”. Usually chickens are unable to read or write, which brings me to the 55 names, and the articles is “j-stored” away –thus– as ‘weapon of mass instruction’ entirely useless.

:chicken:

Silly me. I thought it was a jar that you put money in every time you cursed 🙂

What was the bronze coin?

Am I the only one that finds it offensive that it takes 15 years for an excavation to be published? Is this a product of “publish or perish” thinking that draws out the process for such a a long time? This behavior slows the progress of knowledge to a snails pace.

You are not alone. In the coin world important hoards lie mouldering in museums. To get access to them has to grovel and fill out pointless paperwork and then might not succeed. In Heraklion museum there are objects labelled “unpublished-no photography!” They were dug by Sir Arthur Evans over a century ago!

This situation is not unusual and seems to be the norm.

55 targets in one curse pot… the metaphysical equivalent of an area-fire weapon. Admirably ambitious!

We visited Bath and saw the lead curse scrolls retrieved from the bottom of the hot spring-fed bathing pool. If I recall correctly those were almost all sent against individuals.

It would be interesting to know the effect, if any, these curses had. Was an innocent Roman, target of a curse, walking along a street, be suddenly flattened by a heavy lyre (pianos being some distance off in the future) falling from the clouds? More likely he would be doused with the contents of a Roman chamber pot, but no magic there…