An altar from the late Hellenistic era (ca. 1st century B.C.) has been discovered at the Segesta Archaeological Park in Sicily. It was found just a few centimeters under the surface during ground clearing work in the Southern Acropolis Area.

An altar from the late Hellenistic era (ca. 1st century B.C.) has been discovered at the Segesta Archaeological Park in Sicily. It was found just a few centimeters under the surface during ground clearing work in the Southern Acropolis Area.

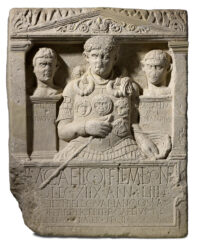

The altar is a sculpted stone piece in the shape of a truncated pyramid and decorated with carved moldings and reliefs. Small round moldings line the base while in the center is a high-relief swag topped with baskets overflowing with flowers and fruit. On the top section of the altar is a terracotta brick placed horizontally with Ionic volutes on each end. This was likely meant to hold relics or references to family heroes or ancestors. It has a niche on the back where a metal hook would have been attached to anchor it to masonry.

A second associated piece found next to it was either a smaller altar or perhaps a support for a cult statue. It has a roughly chiseled surface to aid in plaster adherence.

A second associated piece found next to it was either a smaller altar or perhaps a support for a cult statue. It has a roughly chiseled surface to aid in plaster adherence.  At least three of the sides were covered in plaster originally and likely painted. Today only one small fragment of the plaster survives. The top has a molded cornice and horizontal surface, like the larger altar does. Both pieces were meant for family worship rather than for public devotions.

At least three of the sides were covered in plaster originally and likely painted. Today only one small fragment of the plaster survives. The top has a molded cornice and horizontal surface, like the larger altar does. Both pieces were meant for family worship rather than for public devotions.

Segesta was founded by the Elymians, one of the three cultural groups indigenous to Sicily. Ancient sources record Segesta in territorial competition with Selinunte as early as 580 B.C. It was that long-standing conflict that drove the cities into alliances with Greek polities and colonies. Segesta partnered with Athens in the 5th century B.C. but the alliance could not prevent its destruction by the Greek tyrant Agathocles of Syracuse in 307 B.C. Whoever he didn’t kill he sold into slavery, and the city never fully recovered.

Segesta was founded by the Elymians, one of the three cultural groups indigenous to Sicily. Ancient sources record Segesta in territorial competition with Selinunte as early as 580 B.C. It was that long-standing conflict that drove the cities into alliances with Greek polities and colonies. Segesta partnered with Athens in the 5th century B.C. but the alliance could not prevent its destruction by the Greek tyrant Agathocles of Syracuse in 307 B.C. Whoever he didn’t kill he sold into slavery, and the city never fully recovered.

It supported Carthage in the early years of the 4th century B.C., but ditched it in the First Punic War (264 B.C.), turning to Rome for naval and military succor. It remained a significant port city through the 2nd century A.D., but the ancient sources stop mentioning it after that, and it was abandoned for good at the time of the Arab occupation of Sicily around 900 A.D.

It supported Carthage in the early years of the 4th century B.C., but ditched it in the First Punic War (264 B.C.), turning to Rome for naval and military succor. It remained a significant port city through the 2nd century A.D., but the ancient sources stop mentioning it after that, and it was abandoned for good at the time of the Arab occupation of Sicily around 900 A.D.

The ruins of the Hellenistic city on a steep hilltop overlooking the Gulf of Castellamare are today an archaeological park. There’s a Greek theater and a Doric temple that was never completed.