Archaeologists have unearthed hundreds of important objects in graves from the late Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.) at the Zhaigou archaeological site in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province.

Archaeologists have unearthed hundreds of important objects in graves from the late Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.) at the Zhaigou archaeological site in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province.

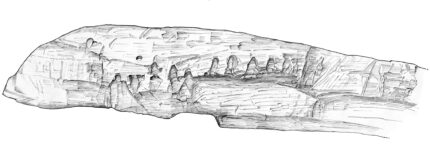

Oracle bones from this period record 70 kingdoms in the north and west. Together these regional powers formed the backbone of the Shang Dynasty’s multi-ethnic political territory. The Zhaigou site was one of the more important regional political centers of the late Shang. Archaeological surveys have discovered large-scale rammed earth buildings, large aristocratic tombs, small cemeteries and evidence of copper casting workshops spanning 11 hills on the Loess Plateau. It is the largest and richest Shang Dynasty site in the region.

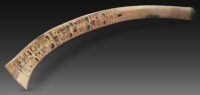

Nine high-status tombs were excavated. Grave goods include bronze chariot and horse fittings, bronze ornaments with turquoise inlay, bones engraved in an animal design with turquoise inlay, gold earrings, copper arrowheads and axes and lacquerware. The tomb with the equestrian fittings is the first Late Shang chariot and horse burial discovered on the Loess Plateau. It is the first Shang Dynasty aristocratic cemetery in northern Shaanxi to be excavated and documented in a scientific archaeological exploration.

Nine high-status tombs were excavated. Grave goods include bronze chariot and horse fittings, bronze ornaments with turquoise inlay, bones engraved in an animal design with turquoise inlay, gold earrings, copper arrowheads and axes and lacquerware. The tomb with the equestrian fittings is the first Late Shang chariot and horse burial discovered on the Loess Plateau. It is the first Shang Dynasty aristocratic cemetery in northern Shaanxi to be excavated and documented in a scientific archaeological exploration.

The settlement, tombs and grave goods are of enormous significance in exploring the political structure and geographic range of the Shang Dynasty in the region. The discovery of the bronze chariot and horse fittings, jade objects, bone artifacts, lacquer ware and tortoise carapaces that match ones found at the ancient city of Yin, last capital of the Shang Dynasty, is evidence the people of the Loess Plateau had close commercial and cultural links to the people of the Central Plains 350 miles to the east, far closer than previously realized.

The settlement, tombs and grave goods are of enormous significance in exploring the political structure and geographic range of the Shang Dynasty in the region. The discovery of the bronze chariot and horse fittings, jade objects, bone artifacts, lacquer ware and tortoise carapaces that match ones found at the ancient city of Yin, last capital of the Shang Dynasty, is evidence the people of the Loess Plateau had close commercial and cultural links to the people of the Central Plains 350 miles to the east, far closer than previously realized.