A rare early Medieval brooch has been restored and put on display at the Museum of Somerset in Taunton.

Discovered by a metal detectorist on farmland near Cheddar in October 2020, the disc brooch is the first of its kind ever found in southwestern England. It is made of silver and copper alloy decorated in the Trewhiddle openwork style which dates it to between 800 and 900 A.D. The decorative motif consists of winding zoomorphic figures interlaced with each other. The surface is dotted with dome-headed riveted bosses, the largest of them (10mm in diameter) in the center. The brooch is unusually large at 91mm in diameter (3.6 inches). The more common examples are 50-60mm in diameter.

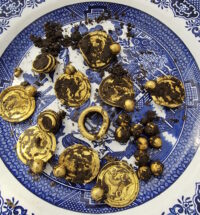

When the Museum of Somerset acquired the brooch in February 2023, its openwork design was still caked with soil and corrosion materials. The museum contracted Drakon Heritage to clean and conserve the brooch. The removal of the crusted soil and corrosion deposits revealed the rich details of the decoration: silver plant and animal forms woven into each other, enhanced by black niello enamel and a gilded back panel.

Amal Khreisheh, the curator of archaeology at the South West Heritage Trust, said: “Conservation has transformed this fascinating brooch and revealed the intricacies. The details uncovered include fine scratches on the reverse, which may have helped the maker to map out the design.

“A tiny contemporary mend on the beaded border suggests the brooch was cherished by its owner and worn for an extended period of time before it was lost.”

Khreisheh said it was likely that it belonged to an important and wealthy person who had access to a goldsmith of exceptional ability.

The conserved Cheddar Brooch will go on display in the Making Somerset gallery starting October 20th.