The Viking warrior grave discovered by homeowners in their backyard in Setesdal, southern Norway, is even richer than it first appeared. When the grave first emerged late last month, a sword, lance, a few gilded glass beads, a fragment of a brooch and pieces of belt buckles were unearthed. Archaeologists from the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo called to the site were not expecting to find much more than a few additional beads, maybe human remains if they were lucky.

The Viking warrior grave discovered by homeowners in their backyard in Setesdal, southern Norway, is even richer than it first appeared. When the grave first emerged late last month, a sword, lance, a few gilded glass beads, a fragment of a brooch and pieces of belt buckles were unearthed. Archaeologists from the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo called to the site were not expecting to find much more than a few additional beads, maybe human remains if they were lucky.

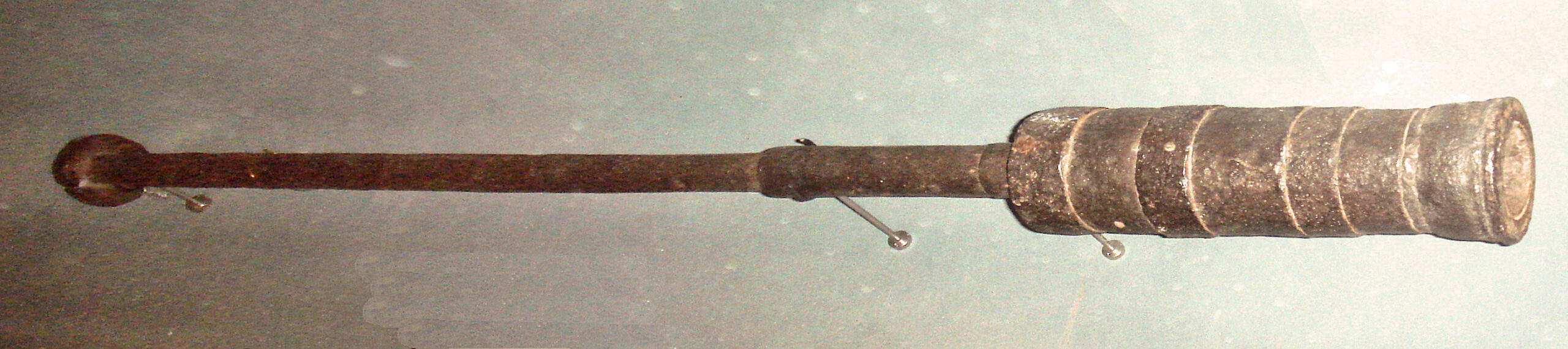

But it turns out those initial finds weren’t even half the contents of this grave. In the past two weeks, an axe head, a shield and some knives have been

discovered, making up a complete set of armature for a Viking warrior. Instead of a few more beads, they found about a hundred more from multiple necklaces. They also found a sickle, an iron oval with an elongated handle that may be a cooking pan, two spindle whorls and fragments of four large oval brooches, one of them almost intact.

discovered, making up a complete set of armature for a Viking warrior. Instead of a few more beads, they found about a hundred more from multiple necklaces. They also found a sickle, an iron oval with an elongated handle that may be a cooking pan, two spindle whorls and fragments of four large oval brooches, one of them almost intact.

Domed oval brooches like these were typically worn in pairs by Viking women to fasten the back straps of  their gowns to the front straps at the shoulders. The two highly decorated cast bronze brooches were often joined by strands of beads. Viking men used brooches to fasten their cloaks, but they are not domed ovals, usually, and they don’t come in pairs. This opens up the possibility that two people, a man and a woman, were buried in the grave, either at the same time or one spouse interred in the other’s reopened grave after their death.

their gowns to the front straps at the shoulders. The two highly decorated cast bronze brooches were often joined by strands of beads. Viking men used brooches to fasten their cloaks, but they are not domed ovals, usually, and they don’t come in pairs. This opens up the possibility that two people, a man and a woman, were buried in the grave, either at the same time or one spouse interred in the other’s reopened grave after their death.

The style of the sword hilt dates the grave to the late 9th, early 10th century. A grave with similar contents was discovered at a neighboring farm in the early 20th century, and two or three other area graves contain swords, brooches and glass beads of the exact same type. These wealthy graves are indicators of the area’s prosperity in the Viking Age.

The style of the sword hilt dates the grave to the late 9th, early 10th century. A grave with similar contents was discovered at a neighboring farm in the early 20th century, and two or three other area graves contain swords, brooches and glass beads of the exact same type. These wealthy graves are indicators of the area’s prosperity in the Viking Age.

Some of the largest iron extraction sites from this time period are found a bit further north in the valley. Extracting iron was something the farmers could do during the wintertime, and iron was exported by the Vikings in massive quantities to Northern Europe and England.

“These exports were so huge that somebody must have gotten quite wealthy from it. And these finds make it tempting to connect the iron extraction business to Valle,” [Museum of Cultural History archaeologist Jo-Simon Frøshaug] Stokke says.

“It’s a captivating thought to imagine such an aristocracy here in Valle, a group of people that have had a style and identity markers that have shown that they belong to this segment of society. Not simply that they are part of the upper echelons because they own swords and such, but that they actually make up a small aristocracy. They’ve dressed in similar ways and brought the same items with them in the grave.”