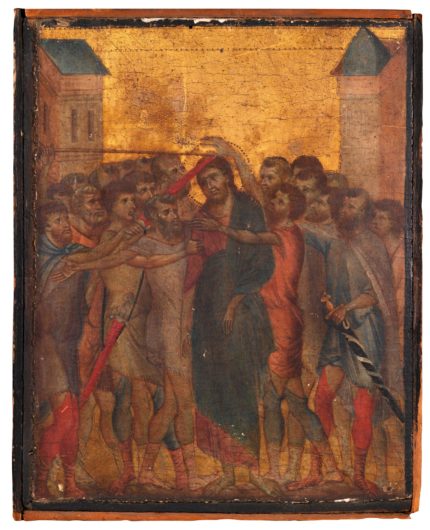

Four years after a late 13th century painting by medieval master Cimabue was discovered in the kitchen of an elderly woman in Compiegne and sold at auction to a private buyer for $26.6 million, Christ Mocked has officially entered the collection of the Louvre Museum.

Four years after a late 13th century painting by medieval master Cimabue was discovered in the kitchen of an elderly woman in Compiegne and sold at auction to a private buyer for $26.6 million, Christ Mocked has officially entered the collection of the Louvre Museum.

It’s been a long, strange journey for the tempera-on-panel depiction of Jesus being taunted by the crowd after his trial before the Sanhedrin. Originally part of an altarpiece diptych of scenes from Christ’s Passion and crucifixion, at some point the panels were disarticulated and sold off individually to collectors keen to acquire one of only 11 known panel paintings by the great Cimabue (1240-1302). The only two other known panels believed to have been part of the original altarpiece are now in the Frick Collection in New York and the National Gallery in London, but only confirmed as the work of Cimabue in 2000.

While the Frick was acquiring its then-unattributed panel and the National Gallery’s was slumbering unrecognized in a Suffolk stately home, Christ Mocked was hanging over a hotplate in a Compiegne kitchen, mistaken by its owner for an old Russian icon. It was only when the lady, then in her 90s, decided to move out of her home and have its contents appraised by a local auction house, that its true identity was discovered. She had no idea where it came from. Louvre researchers think it may have been sold to her ancestors in 1830 by an art dealer from Pisa named Carlo Lasinio who was likely responsibly for selling the other two known panels at the same time.

When it went under the hammer in October 2019, it was the first Cimabue ever to appear at auction, so it was no surprise when the 10-inch panel blew past its pre-sale estimates to sell for nearly $27 million. The buyer was a London collector purchasing it on behalf of the Alana collection, a private collection of Italian Renaissance art in the US. The outfit filed for an export license in December and the French government promptly denied it, declaring the work a national treasure and blocking its export for 30 months to give the Louvre the chance the raise the purchase price and add the Cimabue to its collection.

It’s been more than 30 months, so there was either an extension granted or the announcement was kept under wraps until now. Either way, the Louvre managed to raise the necessary millions thanks to the big revenues from licensing its name to the Louvre Abu Dhabi and a sizable donation from the non-profit American Friends of the Louvre organization.

Christ Mocked will now join Cimabue’s monumental painted panel, Maestà, in the Paris museum. The two works are a fascinating juxtaposition of Cimabue’s range and vision. The Virgin and Child in Majesty Surrounded by Six Angels (aka Maestà) is formally posed in the Byzantine hieratic style. The other two panels of the diptych Christ Mocked was a part of are also painted in that same iconographic style, but Christ Mocked takes a very different approach. It is the first work of Cimabue that seeks to present a naturalism and verisimilitude in the expressions, postures and rendering of space. The faces of the characters in the back are hidden by those of the rows in front of them. They wear contemporary clothing against a backdrop of contemporary Tuscan architecture, conveying their humanity and modernity to the viewers of the time. The materials he used — gold, lapis lazuli, red lacquer — were among the most brilliant and expensive of the time, artfully employed by later masters like Giotto ( c. 1267-1337) and Duccio (1260-1319), who are often credited with introducing the kinds of innovations seen in Christ Mocked.

Christ Mocked will now join Cimabue’s monumental painted panel, Maestà, in the Paris museum. The two works are a fascinating juxtaposition of Cimabue’s range and vision. The Virgin and Child in Majesty Surrounded by Six Angels (aka Maestà) is formally posed in the Byzantine hieratic style. The other two panels of the diptych Christ Mocked was a part of are also painted in that same iconographic style, but Christ Mocked takes a very different approach. It is the first work of Cimabue that seeks to present a naturalism and verisimilitude in the expressions, postures and rendering of space. The faces of the characters in the back are hidden by those of the rows in front of them. They wear contemporary clothing against a backdrop of contemporary Tuscan architecture, conveying their humanity and modernity to the viewers of the time. The materials he used — gold, lapis lazuli, red lacquer — were among the most brilliant and expensive of the time, artfully employed by later masters like Giotto ( c. 1267-1337) and Duccio (1260-1319), who are often credited with introducing the kinds of innovations seen in Christ Mocked.

Maestà is currently undergoing restoration, and Christ Mocked is being examined by conservators. Its condition is very good, with little paint loss and almost no overpainting, so it will be cleaned and conserved to restore its vivid original color before both panels are presented to the public together in 2025.