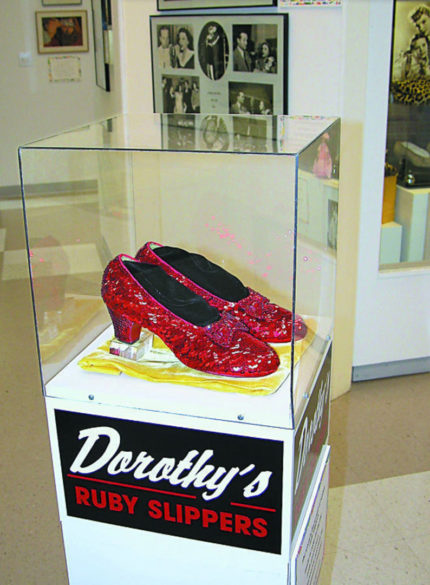

The perpetrator of the daring 2005 smash-and-grab theft of a pair of Ruby Sippers from the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, turns out to be surprisingly clueless. Terry Martin managed to steal the iconic shoes, one of only four surviving pairs of the slippers worn by Judy Garland playing Dorothy in 1939 production of The Wizard of Oz, in less than a minute and keep them under wraps for 13 years, even as authorities and fans never stopped searching for them. Despite this appearance of competence, according to a filing made by his lawyer before his sentencing Monday, Terry Martin thought the Ruby Slippers were festooned with actual rubies rather than dyed glass beads and sequins.

The perpetrator of the daring 2005 smash-and-grab theft of a pair of Ruby Sippers from the Judy Garland Museum in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, turns out to be surprisingly clueless. Terry Martin managed to steal the iconic shoes, one of only four surviving pairs of the slippers worn by Judy Garland playing Dorothy in 1939 production of The Wizard of Oz, in less than a minute and keep them under wraps for 13 years, even as authorities and fans never stopped searching for them. Despite this appearance of competence, according to a filing made by his lawyer before his sentencing Monday, Terry Martin thought the Ruby Slippers were festooned with actual rubies rather than dyed glass beads and sequins.

It beggars belief, but apparently Mr. Martin, who was 57 years old at the time of the theft and was born nine years after the movie’s initial theatrical release, figured they had to be real rubies to justify the million dollars they were insured for. His cunning plan was to pry the rubies off and sell them piecemeal so nobody would be able to trace their origin. He only realized his mistake when a jewel fence he took one of the beads to broke the news that it was made of glass.

Martin had dealt in stolen jewels and had spent time in prison for burglary, his lawyer said. But he had been out of prison for 10 years at the time of the theft and was living quietly in Grand Rapids, a small city 80 miles northwest of Duluth, when an “old mob associate” contacted him about “a job,” his lawyer wrote.

Martin was initially reluctant to get involved, DeKrey wrote. But “old Terry” beat out “new Terry,” and he gave in to the temptation for “one last score,” his lawyer said. […]

Martin used a hammer to smash two window panes in a door of the Judy Garland Museum and broke open a plexiglass case holding the shoes, leaving behind a single red sequin and no fingerprints, court documents said.

But less than two days later, when the unnamed person who traded in stolen jewels told Martin that the gems were worthless replicas, “Terry angrily decided to simply cut his losses and move on,” DeKrey wrote. “He gave the slippers to the associate who had recruited him for the job and told the man that he never wanted to see them again.”

He was serious about that. Martin was only busted in 2018 when other parties tried to blackmail the insurance company for hundreds of thousands of dollars in return for the shoes. The FBI recovered the slippers in a sting operation, but the blackmailers, who were probably organized crime figures, and the mobster who originally recruited Martin back in 2005 were not arrested. Martin refused to implicate anyone else. He just pled guilty to the theft and is facing his fate alone.

His sentence was gentle. Martin has COPD and is in the last months of his life. He was sentenced to time served, a year of probation and to pay the museum $23,000 in restitution for the theft.