An excavation of the Temple of Peace built by Vespasian in the Imperial Forum in Rome has revealed thousands of years of Roman history, without even reaching the imperial era yet.

The Templum Pacis was built by the emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 A.D.) between 71 and 75 A.D. in celebration of his victories in the First Jewish–Roman War. Vespasian had personally led the Roman legions that crushed the rebellion in Galilee in 67 A.D. and after his elevation to the purple took him to Rome in 69 A.D., he left his son Titus behind to besiege Jerusalem. Jerusalem fell to Rome in the summer of 70 A.D. The loot from the sacking of Jerusalem funded the construction of Vespasian’s new temple to Pax, the goddess of peace.

A large and important temple facing what would become the Colosseum, The Temple of Peace is probably best remembered today for something added to it long after Vespasian’s death. It was the home of the Forma Urbis, an incredibly detailed map of Rome 60 feet wide carved on 150 marble slabs that documented the floorplans of every building, monument, bath, street and even staircases in the city to a scale of 1:240. It was hung on an interior wall of the temple by the emperor Septimius Severus in the first decade of the 3rd century. It was damaged in the 410 A.D. sack of Rome by Alaric, and gradually more and more of it was lost. Like much ancient marble, in the Middle Ages it was harvested to make lime. Today only 1,186 pieces of it (10-15% of the original) survive, and they are still being puzzled together.

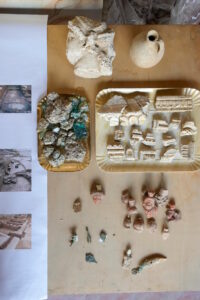

The excavation of the eastern section of the temple, an area never archaeologically investigated before, began in June 2022 and came to a close just last week.

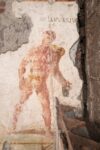

The discovery of cellars and large kilns, which can be easily imagined to have been the fate of many imperial marbles transformed into lime, reveals to archaeologists the evidence of the great complexity of the area, which had not been subject to archaeological investigations until now. Moreover, with the upcoming excavations, thanks also to the funds from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), it will probably be possible to reach the imperial phases and, why not, even the earlier ones. The hope is that this relatively small section of the Imperial Forums, not adequately investigated with the currently used methodologies, may bring some new interesting data to the understanding of an area that is only seemingly well-known: written sources, views, nineteenth-century photographs, and old-style digs (not scientific excavations) from the first half of the twentieth century do not represent a sufficient heritage to understand the phases in a city that has been constantly transforming for millennia like Rome.