The Junction Group earthworks complex in Chillicothe, Ohio, is one of very few remaining ancient Native American ceremonial sites that hasn’t been sliced and diced by roads or train tracks or development. Situated on the south edge of the city at the confluence of the Paint Creek and its tributary North Fork Paint Creek, the earthworks take up about 25 acres of a 90-acre plot that is going up for auction on Tuesday, March 18th. The field belongs to the Stark family who have farmed it for generations but are now reluctantly selling the entire farm, including the earthworks.

The Junction Group earthworks complex in Chillicothe, Ohio, is one of very few remaining ancient Native American ceremonial sites that hasn’t been sliced and diced by roads or train tracks or development. Situated on the south edge of the city at the confluence of the Paint Creek and its tributary North Fork Paint Creek, the earthworks take up about 25 acres of a 90-acre plot that is going up for auction on Tuesday, March 18th. The field belongs to the Stark family who have farmed it for generations but are now reluctantly selling the entire farm, including the earthworks.

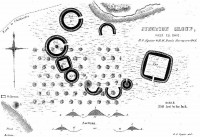

The land has road frontage and is close to city water and sewer lines, which makes it a very attractive parcel for a housing development. There’s already a subdivision kitty corner with the property. Any such construction would destroy the foundations of the earthworks of the Hopewell Culture which we know are still there just underneath the surface. The Junction Group was built 1800-2000 years ago as nine earthworks enclosures: four circular mounds, three crescents, one large square and a quatrefoil. The latter is the only known example of that shape ever discovered in Ohio.

To keep this irreplaceable historical treasure from falling into uncaring hands, the Heartland Earthworks Conservancy, the Arc of Appalachia and other non-profit organizations are working together to raise $500,000 to buy not just the earthworks parcel but the entire farm which is being sold in six lots. If they are successful in acquiring the land, the long-term plan is to turn it over to the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park which is just six miles northwest of the Junction Group. The national park already administers five Hopewell sites in the Paint Creek Valley, and although the process of transferring a sixth site to national park stewardship requires legislative action that can take years, the Arc of Appalachia has already begun the process for another Hopewell earthwork and are confident they can pull it off in the end. They have the full support of the park service in their endeavours.

The Hopewell culture, also known as the Hopewell tradition because it describes a range of different tribes who developed an extensive trade network along the rivers of the northeast and midwest, flourished from around 200 B.C. to 500 A.D. They were the inheritors of the Adena culture who inhabited the same area in the Scioto River Valley in the first millennium B.C. There are two dozen Hopewell ceremonial sites in Ross County alone, most of them consisting of at least one burial mound and several earthwork structures. There is little evidence of settlement on these sites; their purpose appears to have been almost entirely religious.

The Junction Group was first named and documented by Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis in their seminal 1848 work Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. It was the first major work on the archaeology of ancient mounds in the United States and the first publication of the Smithsonian Institution. When Squier and Davis recorded the Junction Group in 1845, the largest mound was seven feet high and some earthenwork walls were at least three feet high with deep ditches on either side.

The Junction Group was first named and documented by Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis in their seminal 1848 work Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. It was the first major work on the archaeology of ancient mounds in the United States and the first publication of the Smithsonian Institution. When Squier and Davis recorded the Junction Group in 1845, the largest mound was seven feet high and some earthenwork walls were at least three feet high with deep ditches on either side.

Since then, farming has worn down the mounds and earthworks so they are no longer visible to the naked eye. It was a magnetic imaging survey in 2005 which revealed that the foundations of the complex are still crystal clear under the plough line. The survey also was the first to recognize that what Squier and Davis thought was a smaller square was actually the unique quatrefoil.

If you’d like to donate to save this irreplaceable resource, you can make a pledge on the Arc of Appalachia website here or pledge or donate on the Heartland Earthworks Conservancy page here. Pledges are very important to this project because the organizations are applying for grants that will match pledged funds and for loans that will be easier to secure with proof of financial backing.

Please spread the word! There are only a few days to go before the auction. So many of these mounds and earthworks are gone forever in Ohio. Let’s stop the Junction Group from succumbing to this tragic fate.

[youtube=http://youtu.be/HUhSdZAeGKU&w=430]