Precious artifacts and bones dating to the Bronze Age have been discovered in the Baradla dripstone cave in northeast Hungary. A team of archaeologists from Eötvös Loránd University has been excavating the cave for four years. Lajos Sándor, a metal detector hobbyist working with the team, was scanning part of the excavation path, an area he’d scanned many times before, when he unexpectedly got a strong signal from behind the rocks. The archaeologists excavated the spot with their special wooden tools and unearthed bronze artifacts, ceramics, human and animal bones from two periods: the Bükk culture from ca. 5000 B.C., and the Bronze Age Kyjatice culture from ca. 1200 B.C.

Precious artifacts and bones dating to the Bronze Age have been discovered in the Baradla dripstone cave in northeast Hungary. A team of archaeologists from Eötvös Loránd University has been excavating the cave for four years. Lajos Sándor, a metal detector hobbyist working with the team, was scanning part of the excavation path, an area he’d scanned many times before, when he unexpectedly got a strong signal from behind the rocks. The archaeologists excavated the spot with their special wooden tools and unearthed bronze artifacts, ceramics, human and animal bones from two periods: the Bükk culture from ca. 5000 B.C., and the Bronze Age Kyjatice culture from ca. 1200 B.C.

The Bükk culture artifacts are pottery fragments with ornate geometric decorations. They abstract patterns and yellow, red, white and black paint distinguish them from the kind of ceramics made by more local peoples. The Bükk were great travelers who came to the northeastern hills from the Hungarian Great Plains, bringing their crafts and well-developed agricultural knowledge.

The Bükk culture artifacts are pottery fragments with ornate geometric decorations. They abstract patterns and yellow, red, white and black paint distinguish them from the kind of ceramics made by more local peoples. The Bükk were great travelers who came to the northeastern hills from the Hungarian Great Plains, bringing their crafts and well-developed agricultural knowledge.

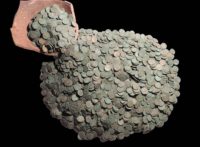

From the latter period is a distinctive grouping is of 59 decorated bronze pieces, most of the disc-shaped, some sparrow-tail shaped. They were found in a hollow near an underground stream covered with a stack of rocks. The way they were piled suggests they may have been mounted on a garment that was folded up and covered with the rock stack. If it existed, the garment has rotted to nothingness over the millennia; not even small traces of it were found.

From the latter period is a distinctive grouping is of 59 decorated bronze pieces, most of the disc-shaped, some sparrow-tail shaped. They were found in a hollow near an underground stream covered with a stack of rocks. The way they were piled suggests they may have been mounted on a garment that was folded up and covered with the rock stack. If it existed, the garment has rotted to nothingness over the millennia; not even small traces of it were found.

The animal bones were found heaped up in piles indicating ritual feasting and/or sacrifices took place in the Baradla cave. The human remains are thought to date to the Neolithic era.

These all point to the Baradla cave having been a sacred place thousands of years ago. [Lead archaeologist Dr. Gábor] Szabó said:

“These days, the cave walls are covered in black soot, but back then they were glowing white, it had to be a beautiful space. Even today, smelling the air of the Baradla cave, you feel that it is a mystical place. It is an astounding interior.”

Szabó thinks that similarly to Stonehenge, the Baradla cave must have been an ancient holy place where communities arrived even from far-away lands to witness the rituals performed there.

“This place could have functioned as a destination for pilgrimages. Sacrifices were made, sacred places were established, there were initiation rituals – the quality ceramics, the piles of animal bones, remains of food materials serve as proof for that.”

The find is all the more remarkable because the cave has been picked over by looters since the 1700s and has been studied and excavated by researchers for 150 years. Today Hungary’s most famous stalactite cave, thousands of tourists tramp through it every day. The treasure was secured by the cave’s mineral output, covered by 8-12 inches of limestone, and by its conversion into a tourist site as the thick limestone was paved with a layer of concrete. The two combined to keep the treasure out of view of looters for centuries.

The find is all the more remarkable because the cave has been picked over by looters since the 1700s and has been studied and excavated by researchers for 150 years. Today Hungary’s most famous stalactite cave, thousands of tourists tramp through it every day. The treasure was secured by the cave’s mineral output, covered by 8-12 inches of limestone, and by its conversion into a tourist site as the thick limestone was paved with a layer of concrete. The two combined to keep the treasure out of view of looters for centuries.

Animal and human bones will be subjected to isotope analysis and radiocarbon dating. The cave’s constant temperature of 53.6ºF is cool enough for good preservation of bone, so there’s a chance researchers might be able to extract viable DNA as well. The bronze and pottery artifacts will be taken to the Hungarian National Museum for conservation and eventual display.

Animal and human bones will be subjected to isotope analysis and radiocarbon dating. The cave’s constant temperature of 53.6ºF is cool enough for good preservation of bone, so there’s a chance researchers might be able to extract viable DNA as well. The bronze and pottery artifacts will be taken to the Hungarian National Museum for conservation and eventual display.

This season’s archaeological excavation will continue through August and the team will return for the last dig next year. After that, the cave will be developed into a treatment center for people with respiratory conditions. It’s not clear to me how this asthma cave scheme will be pulled off, as the cool temperatures and 100% humidity make it unlivable for people today just as it was for people 7,000 years ago, but that’s the plan.