When last we saw our intrepid blogger participate in a Heritage Key challenge, the topic was the most important ancient site in London. Now challenge 3 looms, and this time the topic is a controversial one: should the British Museum give the Rosetta Stone back to Egypt?

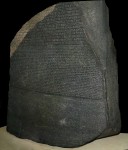

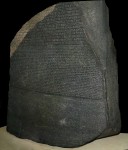

The Rosetta Stone is a carved granodiorite stele made during the reign of Ptolemy V in 196 B.C. The text carved upon it is a single proclamation written in three languages: ancient hieroglyphic, Demotic and classical Greek.

It was discovered in 1799 by French troops in Fort St. Julien, Rosetta (today known as Rashid), Egypt. When I say it was discovered in Fort St. Julien, I mean it was actually a part of the fort. It was found during construction work. At some point in its lifetime, the stone had been re-purposed as building material.

It was discovered in 1799 by French troops in Fort St. Julien, Rosetta (today known as Rashid), Egypt. When I say it was discovered in Fort St. Julien, I mean it was actually a part of the fort. It was found during construction work. At some point in its lifetime, the stone had been re-purposed as building material.

French officer Pierre Francois Xavier Bouchard immediately recognized its archaeological value and packed it off to the French Institute of Egypt in Cairo. When Napoleon’s troops got spanked by the British in 1801, the stone was one of the spoils the victor claimed. It has been on display at the British Museum since 1802, interrupted only twice: once by World War I (1917) and once by loan (October 1972, to the Louvre).

What makes this hunk of volcanic rock worth launching international incidents over is not so much the object itself, but the fact that the juxtaposition of the three languages allowed British polymath Thomas Young and French scholar Jean-François Champollion to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics in the early 1800s for the first time since the language died out in the 5th century A.D.

So should the Rosetta Stone be returned to Egypt? Zahi Hawass, Secretary General of the Egyptian Council of Antiquities, certainly thinks so. He considers it an icon of Egyptian identity that was “raped” by French invaders and as such it belongs in Egypt, its homeland.

His position isn’t quite as firm as it seems, however. He originally asked the British Museum to loan the Rosetta Stone (and several other iconic pieces) to Egypt for the opening of the new Grand Museum at Giza in 2013. The BM’s response was a less-than-felicitous questionnaire about security conditions in the new museum. It was only after that that Hawass shifted approach to demanding repatriation.

The British Museum, for its part, considers the Rosetta Stone to be one of the jewels in its crown. It is the second most visited item (the first is a bog mummy) and most profoundly, it is a nucleus around which the great universal museum grew from modest beginnings as a glorified curiosity cabinet in 1753.

The museum makes some questionable claims, in my opinion, to justify its retention of the Rosetta Stone: that more people can see it in London than would in Egypt, that it has added value in the context of the encyclopedic museums because their vast displays tie together history and culture from many places, that it’s too old and fragile to be moved, that one repatriation would open floodgates that would in short order sweep every last scrap of colonial spoils out the museum doors, that Egypt won’t secure it properly, that Egypt might even be so bold as to keep it once they have it on loan.

The utilitarian argument of the number of people who get to see it doesn’t address the underlying ethical questions at all. The value of its context within the British Museum pales in comparison to its cultural value to the Egyptian people. In this day and age, secure transportation even of extremely fragile antiquities is not a barrier to movement. If the Terracotta Warriors can travel the globe for years, a big slab of rock should be just fine. The floodgates argument is hyperbolic at best given that even Hawass himself only has 5 items on his ideal repatriation wish list, only this one in the BM. The latter two points are just offensive, frankly, hence Hawass’ reaction of going from asking for a loan to demanding repatriation.

But — and my regular readers here might be surprised to see me say this — I don’t actually think the Rosetta Stone should be returned forthwith to the bosom of mother Egypt. Many’s the time I’ve inveighed against looters and the museums, dealers, auction houses and collectors that have enabled the vicious, almost unbearable despoliation of archaeological sites, but once you go back a few hundred years, things are not so cut and dried.

Do the victors get to keep the spoils forever, even when centuries later they have a whole new relationship with the source country which wasn’t even the country they were fighting at the time? Legally, there is no issue here. The question is an ethical one, and although as a point of general principle I tend to side with source countries on these issues, the sticking point for me with the Rosetta Stone is the fact that it has become the premier icon of Egyptology due to the French and British scholarship that followed its discovery.

That is why it is a household name, not because it’s a piece of exceptional beauty and rarity like the bust of Nefertiti in Berlin (also on Hawass’ short list), not because it played a key role in the history of Egypt itself, not because of what it proclaims in those three languages. The Rosetta Stone was the key to unlocking the words of the pharaohs, so of course Hawass is entirely correct that it is an essential piece of Egyptian identity. However, it’s also an emblem of decipherment, a cultural byword recognized around the world as the ultimate key to a past so long obscured.

So my solution to the brouhaha is as follows: the British Museum needs to knock it off with that offensive pukka attitude it takes towards loan requests for culturally sensitive objects, work out the mechanics of the loan like a grownup and act as part of a global community of museums instead of insisting that the world come to them.