The origins of denim are cloudy. Both Nîmes, France, and Genoa, Italy, claim to be its birthplace, and they both have solid grounds for the claim. The André family produced the sturdy cotton twill dyed indigo known as serge de Nîmes (hence denim) for generations, but Genoa claims to have produced jeans for sailors and fishermen since the 1500s. Although those jeans started off brown, eventually they switched to that characteristic indigo color and became known as Bleu de Genes (hence blue jeans).

The Genoese material was cheap and popular all over Europe and even in the US. George Washington himself encountered denim production when he toured the largest cotton mill in the country in Beverly, Massachusetts, in 1789. It would only begin to climb the heights of pop culture fame once Levi Strauss started making his riveted 501 jeans in the 1920s. (He claimed in his advertising to have made his first overalls out of denim for California Gold Rush prospectors in 1849, but he was fibbing. His company only started producing denim overalls in the 1870s, after they patented their rivets.)

One thing we know for sure is denim was a working class fabric. It was tough as hell and could be worn for years by people who rode them hard and, especially in the case of the Genoese sailors, put them away wet. Cowboys, railway workers, fishermen, beggars and lumberjacks didn’t often get their daily lives documented for the historical record, and while high-end textiles are sometimes carefully conserved over the centuries, jeans got worn until they fell apart.

That’s why the discovery of an anonymous Northern Italian painter who depicted poor people wearing denim in the mid to late 1600s is such a surprising find. The fact that he painted the poor going about their business is rare enough; the fact in all but one of his recently-discovered works they’re wearing clearly identifiable jeans skirts, trousers and jackets is unheard of. It has earned him a snazzy anachronistic moniker, too: the Master of Blue Jeans.

That’s why the discovery of an anonymous Northern Italian painter who depicted poor people wearing denim in the mid to late 1600s is such a surprising find. The fact that he painted the poor going about their business is rare enough; the fact in all but one of his recently-discovered works they’re wearing clearly identifiable jeans skirts, trousers and jackets is unheard of. It has earned him a snazzy anachronistic moniker, too: the Master of Blue Jeans.

“This calls into question the entire history we have been telling up until now,” said Francois Girbaud, who partnered with the Paris exhibition. “And that’s what’s fun.”

“In people’s minds, jeans used to be all about Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, about the United States,” he said. “Nimes or Genoa? I don’t have the answer. But it’s amusing to think that jeans already existed in 1655.”

Ten paintings have been attributed to the Italian artist, eight of which are on show in Paris alongside works by contemporaries such as Michael Sweerts or Giacomo Ceruti, loaned from museums and private collections in Rome and Vienna.

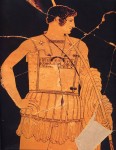

The paintings are currently on display in the Canesso Gallery in Paris. My favorite is “Beggar Boy with a Piece of Pie” (see picture to the right) because that jacket is so totally a jeans jacket. I seriously had one just like it junior high, only I intentionally put tears in mine to look cool. Abject poverty has made Beggar Boy look cool naturally.

The paintings are currently on display in the Canesso Gallery in Paris. My favorite is “Beggar Boy with a Piece of Pie” (see picture to the right) because that jacket is so totally a jeans jacket. I seriously had one just like it junior high, only I intentionally put tears in mine to look cool. Abject poverty has made Beggar Boy look cool naturally.