I can’t take credit for that deliciously grandiose title. It was Selby Kiffer, Sotheby’s Senior Specialist for Historic American Manuscripts, who described the first typewritten pages listing the 13 original rules of basketball as the “Magna Carta of the sport.” Said Magna Carta, as you might have guessed, is for sale.

I can’t take credit for that deliciously grandiose title. It was Selby Kiffer, Sotheby’s Senior Specialist for Historic American Manuscripts, who described the first typewritten pages listing the 13 original rules of basketball as the “Magna Carta of the sport.” Said Magna Carta, as you might have guessed, is for sale.

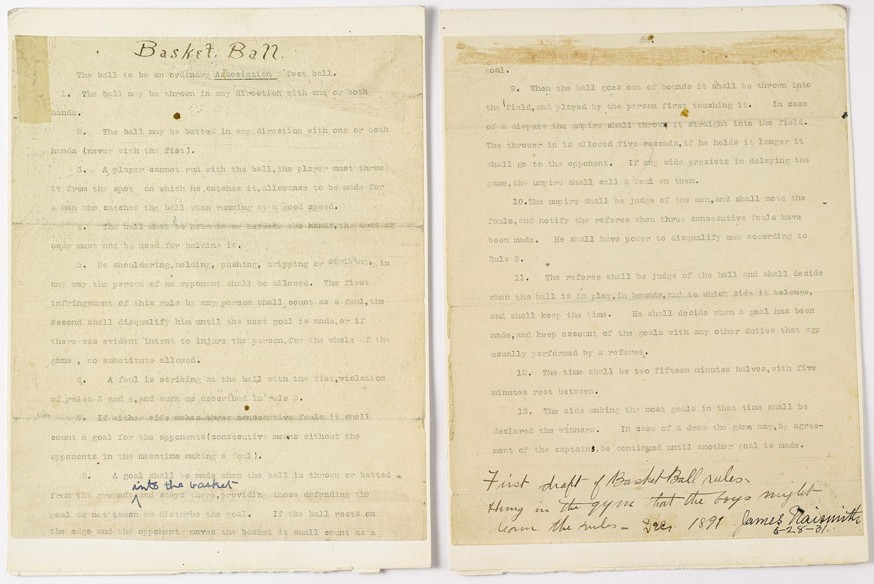

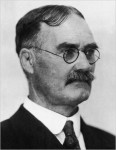

In December of 1891, Dr. James Naismith, a 30-year-old PE teacher at a Springfield, Massachusetts YMCA, dreamed up a sport that could be played indoors to keep those YMCA ruffians busy during the long winter break between the football and baseball seasons. He typed 13 rules on 2 pages and hung them on the gym wall. The sport was instantly popular and the players spread it to other YMCAs. Only 7 years later, Naismith was bringing the game to the University of Kansas and only 30 years after that, the first NCAA tournament took place with 8 teams.

What makes these rules particularly important is that basketball is the only major sport that didn’t evolve from an earlier form. Naismith invented it, the players added their input — including the whole idea of dribbling — the rustic peach baskets and soccer balls were replaced by netted hoops with backboards within 15 years and now the rules are 80 pages long, but it’s still the same game developed from Naismith’s original rules.

The rules memorialized by Naismith are both recognizable and a little bit alien.

The game was to be played with an “ordinary Association football.” Players were not permitted to run with the ball and disqualified for a second foul “until the next goal is made.” But he made a provision for a flagrant foul if “there was evident intent to injure the person.” The only handwritten words in the document read like the most significant ones in Rule 8’s definition of a field goal; in his hand, he inserted “into the basket.”

Perhaps to ensure that people in the future would know the source of the rules, he also wrote in ink in the open space below Rule 13: “First draft of Basketball rules hung in the gym that the boys might learn the rules — Dec. 1891.”

Ian Naismith, James Naismith’s grandson, is offering them for sale. The proceeds will fund the non-profit Naismith International Basketball Foundation, an organization dedicated to promoting good sportsmanship in sport in the spirit of the good doctor. The estimated sale price is $2 million.

Fun fact: This one time Ian thought he’d left the rules in a Kansas City Hooters but then he found them under his seat in the van after all.