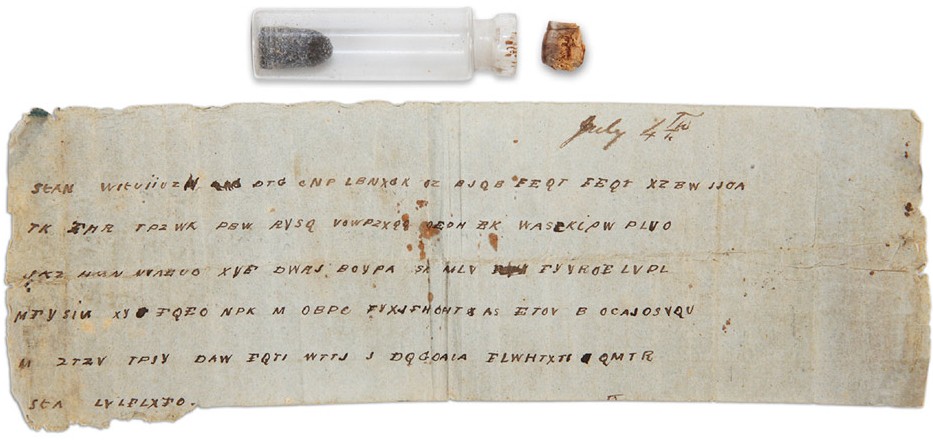

A glass vial containing a coded message from a Confederate commander across the Mississippi from where Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton’s forces were losing the battle of Vicksburg has been decoded. The commander reports that Pemberton can expect no help from him. The message is dated July 4, 1863, the day Pemberton surrendered to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Union army.

The tiny sealed bottle was donated to the Museum of the Confederacy in 1896 by Capt. William A. Smith who fought on the Confederate side at the siege of Vicksburg. It remained unopened and unexamined in the collection for 120-plus years, until collections manager Catherine M. Wright decided to open the bottle and see what the message said.

Inside the bottle they found the coded note, a .38-caliber bullet and a white thread. The bullet was a weight that would allow the vial to sink if the messenger had to hastily dump it in the river upon discovery.

Wright asked a local art conservator, Scott Nolley, to examine the clear vial before she attempted to open it. He looked at the bottle under an electron microscope and discovered that salt had bonded the cork tightly to the bottle’s mouth. He put the bottle on a hotplate to expand the glass, used a scalpel to loosen the cork, then gently plucked it out with tweezers.

The sewing thread was looped around the 6 1/2-by-2 1/2-inch paper, which was folded to fit into the bottle. The rolled message was removed and taken to a paper conservator, who successfully unfurled the message.

But the coded message, which appears to be a random collection of letters, did not reveal itself immediately.

Wright tried to decipher the note herself but was unsuccessful. She contacted David Gaddy, a retired CIA code breaker, and he was able to crack the code in just a few leisurely weeks. Navy cryptologist Cmdr. John B. Hunter confirmed Gaddy’s interpretation.

The note was written in a Vigenère cipher, a fairly simple code that shifts letters a certain number of places, first described in the 16th century by Giovan Battista Bellaso. Blaise de Vigenère created a stronger version 30 years later for the court of Henry III, and in the 19th century its invention was misattributed to him.

The full decoded text of the note is:

Gen’l Pemberton:

You can expect no help from this side of the river. Let Gen’l Johnston know, if possible, when you can attack the same point on the enemy’s lines. Inform me also and I will endeavor to make a diversion. I have sent some caps (explosive devices). I subjoin a despatch from General Johnston.

It wasn’t signed, but it was probably sent by Maj. Gen. John G. Walker of the Texas Division. William Smith served under him at Vicksburg. General Johnston was Gen. Joseph E. Johnston who commanded 32,000 troops south of Vicksburg. He and Pemberton’s forces were separated by 35,000 of Grant’s troops.

Grant’s force besieged Vicksburg for six weeks, reducing the city to near starvation. People were eating dogs and wallpaper paste by the end. They were so bitter about the surrender that for 80 years the city refused to celebrate the Fourth of July.