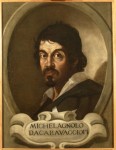

Michelangelo Merisi, aka Caravaggio, was notoriously bad-tempered and violent, constantly getting into physical altercations, confident that his moneyed patrons would fish him out of scrape after scrape. They mainly did, as it happened, and when they didn’t, he just skipped town for a while until the heat was off him. The stories about him have become part of his legend — the bad boy artist who lived fast, died young and left a sunstroked/syphilitic/stabbed/lead poisoned corpse — and it’s difficult to tell fact from gossip.

Michelangelo Merisi, aka Caravaggio, was notoriously bad-tempered and violent, constantly getting into physical altercations, confident that his moneyed patrons would fish him out of scrape after scrape. They mainly did, as it happened, and when they didn’t, he just skipped town for a while until the heat was off him. The stories about him have become part of his legend — the bad boy artist who lived fast, died young and left a sunstroked/syphilitic/stabbed/lead poisoned corpse — and it’s difficult to tell fact from gossip.

Rome’s State Archives contain a myriad primary documents detailing Caravaggio’s many brushes with the law (among other information about his life and work) but until recently they were on the verge of falling apart as the acid in the ink ate away at the parchment. With the Culture Ministry slashing budgets left, right, and center, it took a desperate appeal in the Italy’s version of the Wall Street Journal, Il Sole-24 Ore, to rally a group of private sponsors to donate the funds needed to restore thousands of police logs, court decisions and eye-witness testimony so the legend of bad boy Caravaggio could be fleshed out with the fact of him.

Rome’s State Archives contain a myriad primary documents detailing Caravaggio’s many brushes with the law (among other information about his life and work) but until recently they were on the verge of falling apart as the acid in the ink ate away at the parchment. With the Culture Ministry slashing budgets left, right, and center, it took a desperate appeal in the Italy’s version of the Wall Street Journal, Il Sole-24 Ore, to rally a group of private sponsors to donate the funds needed to restore thousands of police logs, court decisions and eye-witness testimony so the legend of bad boy Caravaggio could be fleshed out with the fact of him.

Now that they’ve been restored, the pages have gone on display at Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, a church that houses the State Archives, along with complementary works of art including Caravaggio’s portrait of Pope Paul V, last on public display 100 years ago, that illustrate the story of his life with heretofore unseen detail and accuracy. Written in a mixture of legal Latin and Roman vernacular (the latter is understandable if you can read modern Italian), the documents are bound into ten volumes of 1,500 parchment pages each. I defy even our best of criminals today to produce so glorious a rap sheet.

Now that they’ve been restored, the pages have gone on display at Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, a church that houses the State Archives, along with complementary works of art including Caravaggio’s portrait of Pope Paul V, last on public display 100 years ago, that illustrate the story of his life with heretofore unseen detail and accuracy. Written in a mixture of legal Latin and Roman vernacular (the latter is understandable if you can read modern Italian), the documents are bound into ten volumes of 1,500 parchment pages each. I defy even our best of criminals today to produce so glorious a rap sheet.

Here are some of the highlights of his arrest record:

4 May 1598: Arrested at 2- 3am near Piazza Navona, for carrying a sword without a permit 19 November 1600: Sued for beating a man with a stick and tearing his cape with a sword at 3am on Via della Scrofa 2 October 1601: A man accuses Caravaggio and friends of insulting him and attacking him with a sword near the Piazza Campo Marzio

24 April 1604: Waiter complains of assault after serving artichokes at an inn on the Via Maddalena19 October 1604: Arrested for throwing stones at policemen near Via dei Greci and Via del Babuino 28 May 1605: Arrested for carrying a sword and dagger without a permit on Via del Corso 29 July 1605: Vatican notary accuses Caravaggio of striking him from behind with a weapon 28 May 1606: Caravaggio kills a man during a pitched battle in the Campo Marzio area

There are all kinds of previously unknown details in the record. For instance, although we know about the brawl in which he killed a man that led to him being condemned to death by Pope Paul V and him having to flee speedily and stay fled for four years, we now know that it was over an unpaid gambling debt and that it was a full-on planned rumble like in The Outsiders or West Side Story. All eight participants, Caravaggio and three of his mates (one of them a captain in the Papal guard and probably a mercenary Caravaggio hired for the occasion) plus their four antagonists are all named in the records. The man he killed was Ranuccio Tommassoni.

The artichoke assault is a new find. Pietro Antonio de Fosaccia, the waiter who bore the brunt of Caravaggio’s artichoke-induced rage, filed a police report about it.

About 17 o’clock [lunchtime] the accused, together with two other people, was eating in the Moor’s restaurant at La Maddalena, where I work as a waiter. I brought them eight cooked artichokes, four cooked in butter and four fried in oil. The accused asked me which were cooked in butter and which fried in oil, and I told him to smell them, which would easily enable him to tell the difference.

He got angry and without saying anything more, grabbed an earthenware dish and hit me on the cheek at the level of my moustache, injuring me slightly… and then he got up and grabbed his friend’s sword which was lying on the table, intending perhaps to strike me with it, but I got up and came here to the police station to make a formal complaint…

To be fair, that’s not great service. Not assault-worthy, mind you, but maybe short tip-worthy.

Another piece of information found in the records is Caravaggio’s exact birth date and location: September 29, 1571, in Milano, not the small town of Caravaggio which gave him his nickname. That means he was older than biographers realized when he first began painting in Rome. He was 19, not 16, which makes him an adult, not the precocious phenom he would later be described as.

Caravaggio died in 1610 in Porto Ercole, and the records shed some light on his passing as well. It seems that he did not die on the beach, as legends would have it, but that controversial bone-hunter Maurizio Merini was right that he died in a hospital.

The Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza exhibit will remain open until May 15. There are no current plans for it to travel.

He was famously prolific, cranking out not just these pamphlets but also books of poetry under his own name and ghostwritten novels at a breakneck pace of 80,000 words a month. He also wrote history books, reference works, literary criticism, joke books (including ones dedicated to ethnic stereotype humor that probably make for cringingly bad reading today), biographies and much more. One of the Little Blue Book manuscripts he wrote,

He was famously prolific, cranking out not just these pamphlets but also books of poetry under his own name and ghostwritten novels at a breakneck pace of 80,000 words a month. He also wrote history books, reference works, literary criticism, joke books (including ones dedicated to ethnic stereotype humor that probably make for cringingly bad reading today), biographies and much more. One of the Little Blue Book manuscripts he wrote,