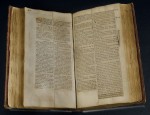

In 1896, just a few weeks after German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen published his discovery of X-rays, H.J. Hoffmans, a high school principal, and Lambertus Theodorus van Kleef, director of a local hospital, put together an X-ray machine of their own from parts they found in Hoffmans’ high school in Maastricht, the Netherlands. They tested it on van Kleef’s daughter’s hand and it worked like a charm, a dangerously huge levels of radiation-releasing charm.

In 1896, just a few weeks after German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen published his discovery of X-rays, H.J. Hoffmans, a high school principal, and Lambertus Theodorus van Kleef, director of a local hospital, put together an X-ray machine of their own from parts they found in Hoffmans’ high school in Maastricht, the Netherlands. They tested it on van Kleef’s daughter’s hand and it worked like a charm, a dangerously huge levels of radiation-releasing charm.

The machine ended up in storage at the Maastricht University Medical Center where it was promptly forgotten until it was dug up last year to use as a visual aid in a documentary on the history of medicine in the area. Curiosity piqued, MUMC medical physicist Gerrit Kemerink decided to run the old machine through its paces and see what it could do.

“To my knowledge, nobody had ever done systematic measurements on this equipment, since by the time one had the tools, these systems had been replaced by more sophisticated ones,” said Dr Kemerink.

Kemerink’s team thought it best to use a cadaver hand to experiment on this time around rather than somebody’s lovely daughter since the radiation emitted by this very early machine was likely to be dangerously high. (People didn’t realize radiation could be harmful until a year after Röntgen’s discovery.) The researchers used the original equipment — an iron cylinder wrapped in wire and a glass bulb called a Crookes tube with electrodes at each end — powered by a modern car battery.

They used both a modern hospital radiation detector and the glass photographic plate Hoffman and van Kleef originally used, and found that using the modern detector the machine took a fairly clear picture but there was some blurring from the wide scatter of the X-rays and the cadaver hand got hit with a dose of radiation dose 10 times higher than it would have received from a modern system. Using the far less sensitive period photographic plate, the team found that the machine gave the skin a dose of radiation 1,500 times higher than it would receive from a modern machine.

They used both a modern hospital radiation detector and the glass photographic plate Hoffman and van Kleef originally used, and found that using the modern detector the machine took a fairly clear picture but there was some blurring from the wide scatter of the X-rays and the cadaver hand got hit with a dose of radiation dose 10 times higher than it would have received from a modern system. Using the far less sensitive period photographic plate, the team found that the machine gave the skin a dose of radiation 1,500 times higher than it would receive from a modern machine.

The researchers were of course protected by a lead shield whenever the machine is on, but the experiments didn’t produce enough radiation to harm them. It sure did look and sound fantastic, though.

“Our experience with this machine, which had a buzzing interruptor, crackling lightning within a spark gap, and a greenish light flashing in a tube, which spread the smell of ozone and which revealed internal structures in the human body was, even today, little less than magical,” they wrote.

It’s very 1931 Frankenstein, only in color. You can see and hear it in action in this video from Wired: