A couple of months ago I wrote about an original Norman Rockwell oil painting that had been brought in for appraisal to the Antiques Roadshow in Eugene, Oregon. The painting of a poor young girl dressing up as a fine lady would be published on the cover of Collier’s magazine on March 29, 1919, after The Saturday Evening Post (and every other mag of decent circulation) had rejected it. I noted that Rockwell’s first Collier’s cover, “War Hero Job Hunting,” had also been rejected by other publishers as too controversial a subject.

A couple of months ago I wrote about an original Norman Rockwell oil painting that had been brought in for appraisal to the Antiques Roadshow in Eugene, Oregon. The painting of a poor young girl dressing up as a fine lady would be published on the cover of Collier’s magazine on March 29, 1919, after The Saturday Evening Post (and every other mag of decent circulation) had rejected it. I noted that Rockwell’s first Collier’s cover, “War Hero Job Hunting,” had also been rejected by other publishers as too controversial a subject.

I asked:

Norman Rockwell’s first Collier’s cover illustration depicts a uniformed World War I veteran being welcomed home by his father and little brother. I’m not sure why it was controversial enough to get rejected by the bigger magazines. The war wasn’t officially over yet — the Versailles Treaty would officially end the war on June 28, 1919 — but armistice had been declared on November 11, 1918, so troops were already coming home and looking for civilian work. Maybe they thought the title implied something malicious, like the war hero is a slacker, or that it described a social problem of veteran unemployment?

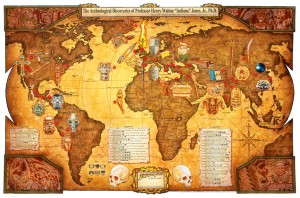

Yesterday, while researching the post on the Indiana Jones map, I got my answer. It’s the latter. Disabled American Veterans, the organization artist Matt Busch will be donating the map proceeds to, was founded as the Disabled American Veterans of the World War (DAVWW) on September 25, 1920 to support soldiers who had been injured fighting in World War I and who returned home facing immense physical, psychological and bureaucratic hardships.

Among many other accomplishments, the DAVWW advocated consolidation of veteran’s programs currently spread out under the jurisdiction of three agencies, the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Public Health Service, and the Federal Board of Vocational Training. It was DAVWW lawyers who got a bill passed establishing the Veterans Bureau, later renamed the Veterans Administration, the predecessor of today’s Department of Veterans Affairs.

Among many other accomplishments, the DAVWW advocated consolidation of veteran’s programs currently spread out under the jurisdiction of three agencies, the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Public Health Service, and the Federal Board of Vocational Training. It was DAVWW lawyers who got a bill passed establishing the Veterans Bureau, later renamed the Veterans Administration, the predecessor of today’s Department of Veterans Affairs.

Medical advances allowed a great many more disabled veterans to return from Europe rather than die on the field as had been so often the case during the Civil War. They couldn’t just go back to their old jobs, though. Some of them were no longer physically able to do what they had done before, some had psychological challenges from the trauma of war, and all of them faced a collapsing economy. Within six months of armistice (November 11, 1918), 2,000,000 soldiers were released from military service, flooding the country looking for work.

At the same time, factories that had been working at full pitch producing weapons, ammunition, uniforms, vehicles, all the complex requirements of wartime industry that had provided more than enough employment to anyone not fighting, shut down production overnight. As Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane wrote in a letter to his brother George on January 30, 1919:

At the same time, factories that had been working at full pitch producing weapons, ammunition, uniforms, vehicles, all the complex requirements of wartime industry that had provided more than enough employment to anyone not fighting, shut down production overnight. As Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane wrote in a letter to his brother George on January 30, 1919:

The one thing that bothers us here is the problem of unemployment. We have not, of course, had time to turn around and develop any plan for reconstruction. Our whole war machine went to pieces in a night. Everybody who was doing war work dropped his job with the thought of [the Paris peace conference] in his mind, with the result that everything has come down with a crash, in the way of production, but nothing in the way of wages or living costs.

In an attempt to forestall the looming issue of unemployable disabled veterans, Congress had passed the Smith-Sears Veterans Rehabilitation Act on June 27, 1918. The bill established a vocational training program for injured soldiers while providing them with a stipend to live on while they learned a new trade. It was inspired by a number of popular state programs that retrained workers injured on the job, was the first federal statute to define legitimate disability, and was the precursor to the Americans with Disabilities Act, as well as the precursor to the far more successful G.I. Bill that would be passed after the next world war.

Unfortunately, the Veterans Rehabilitation Act did not provide the support necessary for the vast majority of disabled veterans. Thanks to an economy that had lost 43% of GNP by the end of 1918, the program was underfunded and swamped by the great numbers of soldiers returning home. Its requirements were also incredibly arcane. All the forms and hoops veterans had to jump through to enroll in the program were major challenges in a society that was still widely illiterate, and of the 675,000 who did apply less than half completed their training. A full 345,000 applicants were denied tout court.

Unfortunately, the Veterans Rehabilitation Act did not provide the support necessary for the vast majority of disabled veterans. Thanks to an economy that had lost 43% of GNP by the end of 1918, the program was underfunded and swamped by the great numbers of soldiers returning home. Its requirements were also incredibly arcane. All the forms and hoops veterans had to jump through to enroll in the program were major challenges in a society that was still widely illiterate, and of the 675,000 who did apply less than half completed their training. A full 345,000 applicants were denied tout court.

The New York Evening Post, as conservative then as its descendant the New York Post is now, ran a series of articles by Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Harold A. Littledale exposing the vast panoply of horrors experienced by veterans applying to the Federal Board of Vocational Training for support under the Rehabilitation Act. In December of 1920, Congressional hearings were held to investigate the board. You can read the full transcript of the hearings online, courtesy of Google Books, or just follow the link to a letter written by a veteran describing his brush with bureaucratic hell.

All these unemployed, increasingly desperate, war-hardened soldiers made people antsy. The Russian Revolution of 1917 had proved that socialism was no distant it’ll-never-happen-here fantasy, and an army of 2,000,000 — even missing a few thousand limbs — was a terrifying prospect to many. Here’s one example of that terror in a June 1921 New York Times article about the Industrial Workers of the World targeting unemployed veterans for their filthy red propaganda. Just a month later, another NYT article describes veterans as “storming” the Welfare Building in Bridgeport, Connecticut, demanding city jobs.

One fellow, Sergeant J.A. Kirk of the 117th Engineers of the Rainbow Division of San Diego, California, in March of 1919 proposed an interesting solution to the problem of widespread veteran employment: move them all to Baja California.

“I suggest a scheme by which we can all become independent. I propose that the 2,000,000 men or more who went to Europe to form ourselves into an organization, with sufficient capital to purchase Lower Callifornia. I am familiar with this undeveloped land, capable of a population of not less than 5,000,000 people which contains at present not to exceed 5,000.

“It has a climate that is unexcelled. It offers to the seeker after health or wealth the opportunity of no other country in the world. This great peninsula is wonderfully rich in gold, silver, copper, tin, onyx, marble and sulphur, none of which has been touched. The west coast of the entire country, lying along the pacific, is the finest citrus fruit country in the world, barring none. Stock raising could be carried on without cost to the owner. Grasses of the nutritious kind grow the year around.

“For agriculture, gardening, poultry, it has no superior. It must, however, be borne in mind that this country is practically virgin. Although it lies contingent to our own country and is only a few hours from San Diego by auto or coastwise boat, it offers to our soldiers an opportunity to pioneer, to build, to create a great State.”

That one didn’t pan out, I can’t imagine why.

So when The Saturday Evening Post‘s conservative editor George Horace Lorimer turned down Norman Rockwell’s “War Hero Job Hunting,” he wasn’t rejecting a wholesome image of a handsome returning hero being welcomed home by his proud father and awed little brother. He was rejecting socialism, revolution, and best case scenario, the prospect of 2,000,000 men suckling at the government teat.