Archaeologists excavating Stalag Luft III, the Luftwaffe POW camp in Lower Silesia made famous by Steve McQueen in The Great Escape, have found a fourth tunnel dug after the failure of the attempt immortalized/fictionalized on film. Although historians knew about the existence of this fourth tunnel, named George, and that it was dug underneath the camp theater, its exact location was a mystery.

Archaeologists excavating Stalag Luft III, the Luftwaffe POW camp in Lower Silesia made famous by Steve McQueen in The Great Escape, have found a fourth tunnel dug after the failure of the attempt immortalized/fictionalized on film. Although historians knew about the existence of this fourth tunnel, named George, and that it was dug underneath the camp theater, its exact location was a mystery.

Using ground-penetrating radar and information from POWs who survived internment, archaeologists spent three weeks looking for George. Now they’ve found it and it still contains a number of artifacts left behind when the Germans hastily evacuated the camp in the middle of the night on January 27, 1945, forcing the 11,000 remaining POWs to march 50 miles in below freezing temperatures deeper behind German lines.

[Artifacts] include yards of wire that inmates stole from the Nazi searchlight power-lines to make electric light in the shaft and tunnel. Also found were numerous “klim tins” – powdered-milk containers – which were hollowed out and used as fat lamps stuck into the side of the tunnel walls when the electricity failed.

Others were joined together to form tubes along which air was pumped for the men digging at the face. Numerous bedboards were used to shore up the workings, and many jagged hinges, bits of old metal pails, hammers and jemmies, used to scour away the sandy soil of the camp, were also excavated.

“It is hardly a treasure in the conventional sense,” said Marek Lazarz, director of the museum that has been built to honour the men of Stalag Luft III. “But it is priceless to us and a time capsule of what life was like back then.

The location turns out to be on the other side of the theater from where experts thought it would be. It ran from under the theater towards the section of the camp where the guards were housed. That’s a counterintuitive choice if your plan is escape, but they could have been aiming for a wooded area between the prison camp and the guard camp. Historians also speculate that perhaps the prisoners were planning to break into the guard barracks to steal weapons to fight their way out and/or to defend themselves from a massacre should Allied troops be closing in.

Since 50 of the 76 prisoners who were able to escape had been executed at Hitler’s personal command, the remaining POWs had very good reason to fear that their jailers would kill them all if it looked like the camp was close to liberation. After the Great Escape, British Intelligence was able to convey orders to the POWs that they were to cease all escape attempts.

According to Squadron Leader Ivor Harris, a prisoner at the camp who ran the makeshift air pump they used to ensure the diggers at the end of the tunnel had breathable air, George was apparently not meant to stage another escape, but rather to be used as “for emergencies only,” which sounds to me like a last resort either for running like hell, fighting or for hiding until Allied troops freed them.

These tunnels really were astonishing pieces of ingenuity and engineering. Underneath the blackish topsoil of the camp was golden sand. The German command had specifically chosen the area because of this contrast, so that if anyone was digging the color of the sand would expose them. Sand is also easy to dig through but very hard to shore up; if you’ve ever dug a tunnel with your hand on the beach you know how it just collapses when you pull your hand out. The Germans also put all the prisoner barracks on stilts to make digging more visible and they put microphones underground so they could hear any excavation noises.

In March of 1943, POWs decided to attempt the impossible. They started digging three tunnels, Tom, Dick and Harry (Nova has a neat interactive map of Harry). They hid the entrance to the tunnels under a chimney, a sewage outlet and a stove in three different barracks. To bypass the microphones, they dug a vertical shaft down deep enough — 9 meters or 30 feet — that the actual tunnel would be dug outside of mic range. They shored up the walls with wooden planks from their bunk beds.

In March of 1943, POWs decided to attempt the impossible. They started digging three tunnels, Tom, Dick and Harry (Nova has a neat interactive map of Harry). They hid the entrance to the tunnels under a chimney, a sewage outlet and a stove in three different barracks. To bypass the microphones, they dug a vertical shaft down deep enough — 9 meters or 30 feet — that the actual tunnel would be dug outside of mic range. They shored up the walls with wooden planks from their bunk beds.

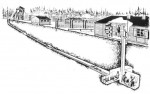

At the base of the shaft, they built three small rooms, a storage chamber for tools and bags of excavated sand, a workshop where they MacGyvered up equipment they needed, and an air pump room where a man constantly pushed a handmade bellows on runners back and forth to send air to the remote digger. The ventilation pipes were made out Klim milk cans, tops and bottoms removed then stuck together.

Those milk cans were also used as lamps initially, filled with mutton fat with a pajama fabric wick. They were so rank and noxious in the confined space of the tunnel, however, that they were soon replaced by actual electric wiring, stolen from German workers who had left it unattended. (The Gestapo executed all those workers after the escape.) The wires were then tapped into the prison circuit board.

Once the POWs started digging the long tunnels, they devised a rope-pull trolley cart system so the digger could send back all the sand he was excavating. That trolley system would also be used to transport the diggers as the tunnel got longer, and transport men the night of the escape. Since the entire tunnel was just two feet by two feet — the size of bed boards used to shore up the walls after digging — and since Harry ended up being the length of a football field, that trolley system was key to the escape plan.

Once the POWs started digging the long tunnels, they devised a rope-pull trolley cart system so the digger could send back all the sand he was excavating. That trolley system would also be used to transport the diggers as the tunnel got longer, and transport men the night of the escape. Since the entire tunnel was just two feet by two feet — the size of bed boards used to shore up the walls after digging — and since Harry ended up being the length of a football field, that trolley system was key to the escape plan.

Six hundred POWs worked on the tunnels, but only 200 of them would get a chance to use Harry. The men who were judged to have worked the most, ones who could speak German, ones who had a history of escape were all given priority. The rest drew lots. Once the 200 were selected, they waited for a moonless night to make their attempt. March 24, 1944, was that night.

It didn’t go well from the beginning. The trap door to Harry was frozen shut. It took them an hour and a half of precious time to get the damn thing open. Harry ended up just a little short, 30 feet from the forest, 45 feet from the guard tower, so even once they were able to start sending POWs through, they had to slow down the process drastically to avoid sentries spotting them. Then an air raid killed the power and part of the tunnel collapsed and had to be rebuilt. That’s why the planned 200 escapees ended up being just 76.

Seventy-three of them were promptly recaptured, 50 of them executed, 17 returned to Stalag Luft III, four were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp where they promptly proceeded to dig a tunnel and escape four months later. Sadly, they were again recaptured. Two Norwegian RAF pilots made it to neutral Sweden after three and a half months in Nazi territory. One Dutch RAF pilot escaped through France to the British Consulate in Spain.

In the aftermath of the escape, the Germans took inventory and discovered just how much material had gone into this daring plan: 4,000 bed boards, 90 double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 52 20-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1,212 bed bolsters, 1,370 beading battens, 1219 knives, 478 spoons, 582 forks, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 1,000 feet of electric wire, 600 feet of rope, 3424 towels, 1,700 blankets and over 1,400 Klim cans.

It’s a testament to the massive testes on these guys that as soon as the heat died down a little, they started all over again with George even though the guards were now counting bed boards every day.