In the wee hours of January 7, 1928, the Thames, swollen by heavy December snowfall and a sudden thaw, burst its banks near Lambeth Bridge right across from the Tate Gallery. Water flooded the street and all the buildings on it, including the nine galleries in the basement of the museum. Tate Gallery director Charles Aitken marshaled staff and volunteers to pump out the water which had reached depths of between five and eight feet, and then remove all the sodden paintings to the dry upper galleries.

In the wee hours of January 7, 1928, the Thames, swollen by heavy December snowfall and a sudden thaw, burst its banks near Lambeth Bridge right across from the Tate Gallery. Water flooded the street and all the buildings on it, including the nine galleries in the basement of the museum. Tate Gallery director Charles Aitken marshaled staff and volunteers to pump out the water which had reached depths of between five and eight feet, and then remove all the sodden paintings to the dry upper galleries.

Among the paintings removed from the flooded basement galleries was The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum, an 8-foot apocalyptic vision of Vesuvius’ 79 A.D. eruption painted in 1821 by John Martin. It had been completely submerged in the flood waters and was severely damaged. It was caked in mud, the paint was flaking off and part of the canvas had torn leaving The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum almost bisected and crucially missing an erupting Vesuvius. Curators at the time considered it a total loss. They rolled it in tissue and put it in storage.

When the Tate decided last year to stage a major exhibition of John Martin’s work, they unrolled the The Destruction for the first time in 82 years. They found the painting in better condition than they expected. Sure, it was still coated in dirt and the paint was still flaking, but it hadn’t disintegrated so the loose paint flakes could be carefully reattached to the canvas and the losses retouched. The missing section was still missing, of course, but given the importance of the painting, the Tate staff decided to take the plunge and fill in even the huge blank.

When the Tate decided last year to stage a major exhibition of John Martin’s work, they unrolled the The Destruction for the first time in 82 years. They found the painting in better condition than they expected. Sure, it was still coated in dirt and the paint was still flaking, but it hadn’t disintegrated so the loose paint flakes could be carefully reattached to the canvas and the losses retouched. The missing section was still missing, of course, but given the importance of the painting, the Tate staff decided to take the plunge and fill in even the huge blank.

It was computer technology that made the replacement of the missing part possible. Experts examined the area on a smaller version of the painting Martin made and on his preparatory sketch for the large one. Restorer Sarah Maisey then created four digital versions that were shown to a test audience. The audience was filmed looking at the four images and their eye movements tracked. The eye-tracking results proved that the eyes of the viewers were primarily focused on the undamaged part of the canvas.

If you look very closely at the painting you can see which is Martin’s brushwork and which is the work of restorer Sarah Maisey. “I’ve tried to tone down a lot of the detail,” she said. “I wanted the overall impact of Martin’s work to have been retained but ultimately wanted people to be able to appreciate what was left of John Martin’s work.”

Maisey admitted that restoring the work of Martin had been a responsibility. “As a conservator you don’t normally have to paint large sections, you do small filling in of losses, so this was something quite different. I think he’d be happy. His work was about impact.”

The restoration is reversible should future generations think it wrong, but for now it goes on display at the biggest Martin show ever.

John Martin: Apocalypse runs from September 21st to January 15, 2012, and is the not only the first major Martin exhibit in 30 years, but is also largest display of his work ever seen. Visitors will be able to see 120 of his works, from immense Biblical and historical apocalypse scenes, to sketches, watercolors, mezzotints and even his engineering plans.

John Martin’s paintings were dismissed by the snooty art academy established as lurid and “common.” Nineteenth century art critic and taste arbiter John Ruskin said “Martin’s works are merely a common manufacture, as much makeable to order as a tea-tray or a coal-scuttle.” Of course, John Ruskin famously refused to have sex with his wife when on their marriage night he was shocked to find out that women have pubic hair, so consider the source.

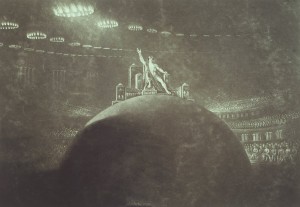

He had a vast fan base among the plebes, though, and artists in a variety of media have felt his influence. Stop-motion innovator Ray Harryhausen modeled his Olympus on the city on a hill in Martin’s Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still Upon Gibeon. George Lucas was inspired by Satan presiding at the Infernal Council (1824-26), one of Martin’s engraved illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, when designing the Senate hall in The Phantom Menace.

Comic book writer Alan Moore is another of Martin’s contemporary fans in the creative world. He artfully described Martin’s The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah as: “This is the terror of the world’s edge, is the vertigo of an accelerated culture. Out beyond the lights of every city, every town and every century, this is the abyss that abides.”