For five short years, between 1844 and 1849, Montreal was the capital of the Province of Canada. The Crown provinces of Upper Canada (English-speaking Ontario) and Lower Canada (French-speaking Quebec) were united in 1841 and three years later the capital was moved from Kingston, Ontario to newly renovated buildings in St. Anne’s Market in Montreal.

These were not easy days for our neighbors to the north. The repeal of the Corn Laws, protectionist legislation which had privileged Canadian exports by applying lower tariffs, in 1846 had left the Canadian economy reeling. With bankruptcies and defaults on the rise, Parliament passed a law indemnifying certain Lower Canadians who had lost property during the Rebellions of 1837-1838, aka the Patriots’ War, uprisings against the Crown that sought political reforms. Similar laws had been passed in aid of Upper Canadians, but the rebellion was so identified with French Lower Canada that Anglophones considered the new indemnity act the government “paying the rebels.”

These were not easy days for our neighbors to the north. The repeal of the Corn Laws, protectionist legislation which had privileged Canadian exports by applying lower tariffs, in 1846 had left the Canadian economy reeling. With bankruptcies and defaults on the rise, Parliament passed a law indemnifying certain Lower Canadians who had lost property during the Rebellions of 1837-1838, aka the Patriots’ War, uprisings against the Crown that sought political reforms. Similar laws had been passed in aid of Upper Canadians, but the rebellion was so identified with French Lower Canada that Anglophones considered the new indemnity act the government “paying the rebels.”

In early 1849, the bill left committee and debate began. The English-language press was almost uniformly opposed to the bill (only one small daily published by a cabinet member supported it), just as the Francophone press uniformly supported it. The bill was amended to ensure that nobody convicted of treason during the rebellion would be reimbursed for their losses, but that did not satisfy its increasingly rabid opponents. The Rebellion Losses Bill passed both Houses of the Provincial Parliament on March 9.

All that was left was for the Provincial Governor, Lord Elgin, son of the Parthenon chiseler, to sign the bill. That wasn’t a foregone conclusion. Elgin was not a fan of the bill. Still, the bill had passed with solid majorities in both houses from Upper and Lower Canada delegates, and the Whig government of Lord John Russell in London supported it, so in the end Lord Elgin signed it into law on April 25, 1849.

When he left the Parliament building at 6:00 PM, he was greeted by a throng of irate Anglos. They pelted his person and then his carriage with rotten fruit and rocks, forcing him to flee at a gallop. A meeting was called for later in the evening supported by an incredibly incendiary Extra edition of the Montreal Gazette.

When Lord Elgin — he no longer deserves the name of Excellency — made his appearance on the street to retire from the Council Chamber, he was received by the crowd with hisses, hootings, and groans. He was pelted with rotten eggs; he and his aide-de-camps were splashed with the savory liquor; and the whole carriage covered with the nasty contents of the eggs and with mud. When the eggs were exhausted stones were made use of to salute the departing carriage, and he was driven off at a rapid gallop amidst the hootings and curses of his countrymen.

The End has begun.

Anglo-Saxons! you must live for the future. Your blood and race will now be supreme, if true to yourselves. You will be English “at the expense of not being British.” To whom and what, is your allegiance now? Answer each man for himself.

The puppet in the pageant must be recalled, or driven away by the universal contempt of the people.

In the language of William the Fourth, “Canada is lost, and given away.”

A Mass Meeting will be held on the Place d’Armes this evening at 8 o’clock. Anglo-Saxons to the struggle, now is your time.

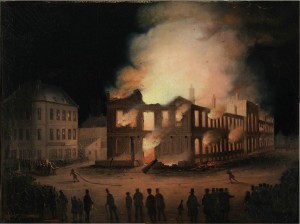

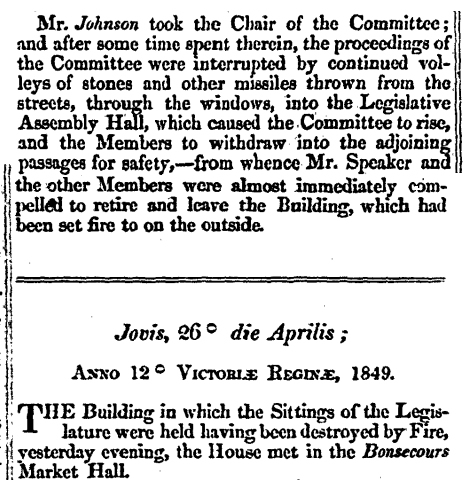

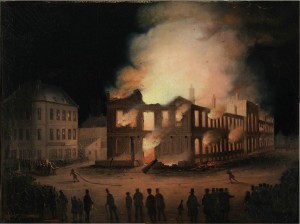

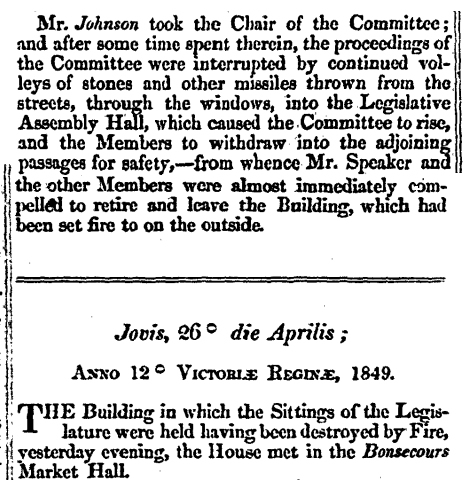

Almost 2000 men went to that meeting. At first they worked on a petition to Queen Victoria demanding Elgin be recalled. Then the petition was set alight and the meeting became a mob that descended upon the Parliament building. The House was actually still in session, working late on a question of establishing an appeals court, when the crowd descended hollering imprecations, throwing stones and finally, setting the building on fire. The last entry for the day and the new entry for the next in the Journals of the Legislative Assembly put it succinctly:

The Parliament building was a total loss, including the libraries and archives of Upper and Lower Canada which had been consolidated after Union. Two hundred books out of 23,000 were saved, as well as a portrait of Queen Victoria. The gilded pine Royal coat of arms which hung above the Speaker’s chair was presumed destroyed.

A hundred and thirty-plus years later, former Toronto MP and Canadian Solicitor-General Robert Kaplan was browsing a flea market in New York state when he found a gilded pine Royal coat of arms that looked a little worse for wear. The vendor told him it was the very same coat of arms that had once hung in the Parliament building when it succumbed to riotous flame in 1849. There were burn marks on the back and missing parts that suggested the story could be true, but Kaplan didn’t explore the connection to see if the artifact was authentic. Instead, he paid the Quebecois dealer $300 and hung the coat of arms above the piano in his New York apartment. He also touched up some of the gilding and let his kids color it with crayons.

A hundred and thirty-plus years later, former Toronto MP and Canadian Solicitor-General Robert Kaplan was browsing a flea market in New York state when he found a gilded pine Royal coat of arms that looked a little worse for wear. The vendor told him it was the very same coat of arms that had once hung in the Parliament building when it succumbed to riotous flame in 1849. There were burn marks on the back and missing parts that suggested the story could be true, but Kaplan didn’t explore the connection to see if the artifact was authentic. Instead, he paid the Quebecois dealer $300 and hung the coat of arms above the piano in his New York apartment. He also touched up some of the gilding and let his kids color it with crayons.

There it remained until last year when Kaplan read that the Pointe à Callière Museum was expanding its excavation of the Place D’Youville Ouest, the site of the former Parliament building, looking for surviving artifacts. He wrote to the museum telling them about his flea market find and offering to donate the piece if they could confirm its authenticity. They could.

On Friday, a beaming Francine Lelièvre, the museum’s director, made it official: The coat of arms is indeed the one that hung above the Speaker’s chair when an enraged mob torched the Parliament building on April 25, 1849, she said at a press conference where she and Kaplan unveiled the donation.

On Friday, a beaming Francine Lelièvre, the museum’s director, made it official: The coat of arms is indeed the one that hung above the Speaker’s chair when an enraged mob torched the Parliament building on April 25, 1849, she said at a press conference where she and Kaplan unveiled the donation.

Visible damage, like the lion’s and unicorn’s missing heads, testify to the violence that laid waste to the building and a library containing government archives dating back to New France.

“A man sat on the Speaker’s chair, proclaimed the Assembly dissolved, and tore off and broke the coat of arms that crowned the podium and chair,” wrote a witness, Amédée Papineau, the son of Patriote leader Louis-Joseph Papineau.

Kaplan is sorry to see it go, but delighted to see it take its proper place in the history of Montreal and of Canada. He played an instrumental role simply by being the person who stumbled on it in New York. How many other people shopping the flea market that day would have even had occasion to realize and embrace its historical importance?

The Pointe à Callière Museum plans to construct an elaborate archaeological complex covering nine historical sites including the burned Parliament location, which will display some of the 50,000 artifacts from different periods found during the excavation while also preserving and displaying the remains of area historical buildings. The sites will be linked to each other by the William Collector Sewer, an underground tunnel 400 meters (1213 feet) long which is yes, a historical sewer, and which will combine exhibition space with a no-traffic, no-inclement weather, pedestrian-only look at the bowels of Montreal. For more about this fascinating project, see the Pointe à Callière website.

The 210-year-old bronze bell cast by Revere & Sons purchased this summer from the First Baptist Church of Westborough was raised into the steeple of Boston’s Old South Meeting House on Sunday.

The 210-year-old bronze bell cast by Revere & Sons purchased this summer from the First Baptist Church of Westborough was raised into the steeple of Boston’s Old South Meeting House on Sunday.  Other than the ceremonial gaveling, however, the Revere bell has not been rung yet. The striking mechanism needs a couple of weeks more work before the bell can peal once again. The bell itself, despite its age and an incident in 1938 when it was torn out of the Westborough steeple into a cemetery by a hurricane, is in excellent condition. Its wooden elements — the yoke and frame on which it rests and the bell wheel — needed far more attention than the bell itself. The yoke and frame are original and so were carefully restored.

Other than the ceremonial gaveling, however, the Revere bell has not been rung yet. The striking mechanism needs a couple of weeks more work before the bell can peal once again. The bell itself, despite its age and an incident in 1938 when it was torn out of the Westborough steeple into a cemetery by a hurricane, is in excellent condition. Its wooden elements — the yoke and frame on which it rests and the bell wheel — needed far more attention than the bell itself. The yoke and frame are original and so were carefully restored.