In honor of the 412th anniversary of the burning at the stake of Giordano Bruno, Dominican friar, philosopher, astronomer and master of mnemonic devices so complex he was thought to have magical powers, the Vatican Secret Archives announced Friday that they are releasing a contemporary summary of his trial and a companion smartphone app.

In honor of the 412th anniversary of the burning at the stake of Giordano Bruno, Dominican friar, philosopher, astronomer and master of mnemonic devices so complex he was thought to have magical powers, the Vatican Secret Archives announced Friday that they are releasing a contemporary summary of his trial and a companion smartphone app.

The detailed Holy Office transcripts of Giordano Bruno’s trial were destroyed between 1810, when Napoleon demanded files from the Vatican Archives be sent to Paris, and 1815-1817 when the files were returned to Rome. We don’t know what got destroyed when, exactly, but records do note that one Marino Marini, the man tasked by Pius VII with bringing the Vatican Archives back to Rome from Paris, considered the trial transcripts of the Holy Office useless at best, at worst harmful since they might taint the reputation of the defendants’ descendants. He and Cardinal Consalvi decided to shred entire volumes of them, then soaked the pieces in water and sold the mash to a Parisian cardboard factory for 4,300 francs. Over 2,600 trial transcripts were lost during this period.

All we have left of the Bruno trial is a summary written in 1598, two years before his execution, and preserved in a volume labeled “Miscelleanea Armadi.” It was rediscovered on November 15, 1940 by Cardinal Angelo Mercati, Prefect of the Vatican Archives, who published it in 1942. It’s that volume that will be on public display at the Lux in Arcana exhibit starting February 29th. The app will be made available the same day.

Thanks to the technological partnership with Accenture, the global management, consulting, technology and outsourcing company, as of February 29th, when the exhibition opens, a sophisticated app that was developed specifically for the Vatican Secret Archives on this occasion will make it possible, for example, to focus your tablet or smartphone on the statue of Giordano Bruno at Campo de’ Fiori and see his pyre burst into flame on your device’s display, to open the documents related to the trial of the Dominican friar and philosopher, and to call up videos with further information on his life and his ideas. The app that Accenture developed also makes it possible to explore all the documents in the exhibition with multimedia in-depth contents, thereby heightening the cultural and emotional experience of the event.

It looks like this:

It’s rather hardcore, especially considering the Church’s statement of sorrow at the “sad episode” and Bruno’s “atrocious death” released on February 17, 2000, the 400th anniversary of the execution. From Cardinal Angelo Sodano’s excruciatingly carefully worded statement:

“It is not our place to express judgments about the conscience of those who were involved in this matter. Objectively, nonetheless, certain aspects of these procedures and in particular their violent result at the hand of civil authority, in this and analogous cases, cannot but constitute a cause for profound regret on the part of the Church.”

I won’t lie, though, it sounds like a pretty kickass app, not so much for the heretic-on-fire screen cap but rather for the easy access to the documents and videos.

The press release says that the Bruno documents are available on the Lux in Arcana website, but all I could find was a short overview of the trial and execution, not the full text. There was a more detailed overview with quotes from the summary available on the Vatican Secret Archives website as recently as last May, but it’s offline now. You can still see it using the Wayback Machine, thankfully.

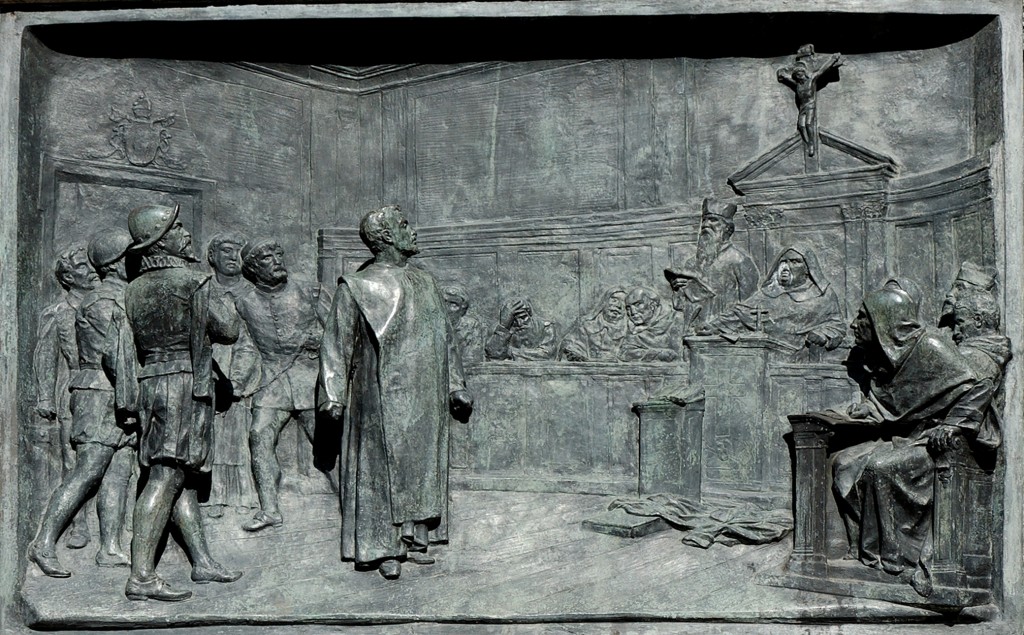

Giordano Bruno was imprisoned in Rome for seven years, from 1593 when he was transferred from his heresy trial in Venice into the hands of the Roman Inquisition until his auto-da-fé in 1600. His trial took place between 1593 and the censoring of his books in 1597. That’s where the summary ends. In 1598 the Curia left Rome, following Clement VIII to the Duchy of Ferrara which he claimed for the Papal States after the death of the childless Alfonso II d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. They left Bruno idling in jail. By the time the trial resumed with interrogatory number 20 in February 1599, Bruno was willing to offer a partial abjuration of the beliefs deemed heretical in return for his neck. He reiterated that willingness during the 21st interrogation in early September 1599.

Then, on September 16, 1599, he changed his mind. He sent the Pope a memo reasserting all of his beliefs and refusing abjuration. The Pope was not pleased. When Bruno stood his ground, refusing to abjure within the 40 day window the Holy Office had allotted him, the deal was sealed. At dawn on February 17, 1600 he was led to Campo de’ Fiori with manacles around his wrists and a bit in his mouth to keep that forked tongue of his from poisoning any listeners with his heresies. There he was stripped naked, tied to a stake and burned alive.

His execution was controversial at the time, and has remained so. That long-forgotten trial summary that was rediscovered in 1940 had actually been rediscovered first in 1886 by Benedictine friar Gregorio Palmieri, keeper of the Vatican Archives. The conflict between the Holy See, sole remnant of the Papal States since Italy’s final unification in 1870, and the secular Kingdom of Italy was in full force. The summary was seen as a major hot potato that Italy’s humanists (and Freemasons) would use to rally opposition to the Holy See; thus it was hidden in the Pope’s private archive — i.e., the Vatican Secret Archive — and its existence was kept secret both within the Vatican and from the outside world.

Freemasons had, in fact, during that same period hit the Catholic Church hard with Giordano Bruno. In 1884, Pope Leo XIII released the encyclical Humanum Genus, in which he explained how Freemasons were advancing the cause of Satan and evil in the world, in opposition to the Church which had only ever advanced the cause of God, Jesus and good. In 1885, an international committee of students, intellectual luminaries including Victor Hugo and Henrik Ibsen, and yes, Freemasons, convened to discuss raising a monument to Giordano Bruno on the site of his execution in Campo de’ Fiori.

Freemasons had, in fact, during that same period hit the Catholic Church hard with Giordano Bruno. In 1884, Pope Leo XIII released the encyclical Humanum Genus, in which he explained how Freemasons were advancing the cause of Satan and evil in the world, in opposition to the Church which had only ever advanced the cause of God, Jesus and good. In 1885, an international committee of students, intellectual luminaries including Victor Hugo and Henrik Ibsen, and yes, Freemasons, convened to discuss raising a monument to Giordano Bruno on the site of his execution in Campo de’ Fiori.

The Church did not agree with this plan, but the secular authorities of Rome, keen to put distance between the new municipality and the Church’s ancient fiefdom, went ahead with it anyway. Freemason Ettore Ferrari (no relation to the car) was commissioned to build the statue. His Bruno wears a Dominican habit, his head bowed, his hood shadowing his face, his chained hands holding a book of his writings. It was inaugurated in 1889.