After 30 years of searching one particular field on the Channel Island of Jersey, metal detectorists Reg Mead and Richard Miles have found an enormous hoard of Roman and Celtic coins from approximately 50 B.C. Archaeologists have excavated it from the clay in a solid block measuring 55 x 31.5 x 8 inches and weighing three quarters of a ton. The block contains an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 coins, for a possible total market value of $5-16 million (£3-10 million).

After 30 years of searching one particular field on the Channel Island of Jersey, metal detectorists Reg Mead and Richard Miles have found an enormous hoard of Roman and Celtic coins from approximately 50 B.C. Archaeologists have excavated it from the clay in a solid block measuring 55 x 31.5 x 8 inches and weighing three quarters of a ton. The block contains an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 coins, for a possible total market value of $5-16 million (£3-10 million).

Mead’s and Miles’ epic quest began after a woman told them that her father had found some ancient coins when he removed a hedgerow from a field. The coins had been buried in an earthenware pot which shattered when the plant was uprooted, scattering silver coins all over the place. Father and daughter collected the coins in a small potato sack, then ploughed under the remains of the pot and other assorted debris. She described the coins to them and they recognized them as Iron Age coins from when the Brittany Celts lived on Jersey.

She didn’t remember exactly where the discovery was made, just the general area, and the current owner of the field farmed it actively so he would only allow them to search during a brief window after harvest. For 30 years, they searched the field during that brief window, a total of maybe 15 hours of work each year. When time was up, they had to wait until the next year’s crop was in to try again.

In February of this year, they found something: 60 Celtic coins, 59 of them silver and one of them gold. After three decades coming up empty, those 60 coins signaled that they might have finally found the location the farmer’s daughter had told them about so long ago. They dug down deeper and found a large solid object. Reg Mead dug up a chunk of earth from the top and found five or six silver coins.

In February of this year, they found something: 60 Celtic coins, 59 of them silver and one of them gold. After three decades coming up empty, those 60 coins signaled that they might have finally found the location the farmer’s daughter had told them about so long ago. They dug down deeper and found a large solid object. Reg Mead dug up a chunk of earth from the top and found five or six silver coins.

They immediately stopped what they were doing and reported the find and location to Jersey Heritage. Jersey Heritage sent staff archaeologists to explore the find and enlisted the aid of Robert Waterhouse from the Société Jersiaise, Dr. Philip de Jersey, Celtic coin expert and States of Guernsey archaeologist, plus volunteers including the finders, the farmer who owns the land and their family members.

Jersey Heritage’s curator of archaeology Olga Finch said: “This is an incredibly important archaeological find of international significance.

Jersey Heritage’s curator of archaeology Olga Finch said: “This is an incredibly important archaeological find of international significance.

“The fact that it has been excavated archaeologically is also rare and will greatly enhance the level of information we can glean about the people who buried it.

“It is an amazing contribution to the study of Celtic coins. We already have a number of very important Iron Age coin hoards found in the island, but this new addition will make Jersey a magnet for Celtic coin researchers. It reinforces just how special Jersey’s archaeology is.”

Dr. de Jersey agrees, noting that coin specialists often spend their lives researching their field by looking at pictures in books or at artifacts behind glass in museum exhibits. Getting the chance to excavate coins in situ is a once in a lifetime opportunity.

The finders and landowner would like to see the hoard exhibited in Jersey, but the question of who owns it and is entitled to reimbursement of its value is up in the air. Jersey is a self-governing Crown Dependency, and has been since 1204 when King John lost all his lands in Normandy to French King Philip II Augustus but was allowed to keep the Channel Islands.

[Reg Mead] said: “We have declared this hoard as the trove, treasure trove, which was an ancient law that gave you, if within a reasonable amount of time you declared them, the full monetary value. We are testing that case because the powers that be have said the practice of trove doesn’t exist in Jersey any more.”

Mr Mead said it was the first important find with metal detectors ever in Jersey.

He said: “There are two laws, in Jersey anyone who wants to follow the law can use the English or the old French. If they don’t like the practice of trove then the old French law is finders keepers. Richard, myself and the land owner have an agreement between us, we are entitled to that hoard.”

It will take researchers a long time to excavate all the individual coins from the block and the estimated numbers may change like they have with the Beau Street Hoard, but it’s likely this will prove to be the largest Iron Age hoard ever discovered on Jersey. Before this, the largest find was more than 11,000 coins discovered in 1935 at La Marquanderie.

It will take researchers a long time to excavate all the individual coins from the block and the estimated numbers may change like they have with the Beau Street Hoard, but it’s likely this will prove to be the largest Iron Age hoard ever discovered on Jersey. Before this, the largest find was more than 11,000 coins discovered in 1935 at La Marquanderie.

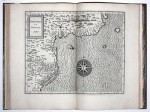

Most of the hoards found in Jersey have been coins from the Coriosolite tribe, a Celtic tribe from what is now Brittany on the northwestern coast of France. First century B.C. hoards are the most common because the populations were under pressure from Julius Caesar’s legions. Caesar describes his encounters with the coastal tribes of the area he called Armorica in The Gallic Wars. The Coriosolite, aka Curiosolite, aka the Curiosolitae are first mentioned in Book 2, Chapter 34 as one of the maritime states that surrendered to his delegate, Publius Licinius Crassus (son of Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the richest men in history, famed for his brutal defeat of Spartacus and for joining Caesar and Pompey in the First Triumvirate) in 57 B.C.

That surrender didn’t take. A year later, the Veneti, the most prominent of the Armorican tribes, along with their Armorican neighbors captured some of Caesar’s officers to exchange them for hostages the Romans had taken. Caesar had to muster all the considerable engineering talents of the Roman army to fight the Veneti in their well-defended strongholds. When they fled to the sea, Caesar had his troops build ships, but they couldn’t compete with the locals’ heavy navy and sailing expertise in the treacherous waters of the Channel and Atlantic.

That surrender didn’t take. A year later, the Veneti, the most prominent of the Armorican tribes, along with their Armorican neighbors captured some of Caesar’s officers to exchange them for hostages the Romans had taken. Caesar had to muster all the considerable engineering talents of the Roman army to fight the Veneti in their well-defended strongholds. When they fled to the sea, Caesar had his troops build ships, but they couldn’t compete with the locals’ heavy navy and sailing expertise in the treacherous waters of the Channel and Atlantic.

He did it in the end, though. He destroyed the Veneti fleet using giant billhooks to sever the lines used to hoist the mainsails. With the sails on the deck, the Celtic ships were entirely out of commission. They couldn’t even row because the huge sails cloaked the deck. Caesar then went from coastal town to coastal town and killed everyone. Those he didn’t kill he sold into slavery. The few who managed to get away fled to nearby Jersey and/or went on to Britain, hence the preponderance of Coriosolite hoards discovered in Brittany and Jersey.

The Daily Mail article has the best pictures of the hoard. The BBC has video of the excavation and crane lifting out the block.

The UK National Archives have uploaded hundreds of pictures of colonial-era Canada just in time for Canada Day. On July 1, 1867, the British North America Act (known in Canada as the Constitution Act since 1982) united the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Province of Canada into a federal dominion of four provinces. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick remained the same; the Province of Canada was divided into Ontario and Quebec.

The UK National Archives have uploaded hundreds of pictures of colonial-era Canada just in time for Canada Day. On July 1, 1867, the British North America Act (known in Canada as the Constitution Act since 1982) united the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Province of Canada into a federal dominion of four provinces. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick remained the same; the Province of Canada was divided into Ontario and Quebec. The pictures come from the Colonial Office’s Photographic Collection. There are 12 sets of pictures, from a collection taken during the Prince of Wales’ (the future Edward VIII who abdicated to marry Wallis Simpson) 1919 tour of Canada, to regional collections depicting grand natural vistas and the minutiae of daily life. You’ll find some of the first photographs ever taken of Canada in the 1850s buried in the sets, along with classic 1960s advertising from the National Film Board of Canada. You’ll also find a lot of First Nations misery documented, and some unpleasant period terminology like “half breed.”

The pictures come from the Colonial Office’s Photographic Collection. There are 12 sets of pictures, from a collection taken during the Prince of Wales’ (the future Edward VIII who abdicated to marry Wallis Simpson) 1919 tour of Canada, to regional collections depicting grand natural vistas and the minutiae of daily life. You’ll find some of the first photographs ever taken of Canada in the 1850s buried in the sets, along with classic 1960s advertising from the National Film Board of Canada. You’ll also find a lot of First Nations misery documented, and some unpleasant period terminology like “half breed.”

The Canadian Border set documents the expedition to map the boundary between Canada and the United States from 1872 to 1876. It was a joint project by participants from the United States Northern Boundary Commission, Royal Engineers from the British North American Boundary Commission, Canadian First Nations and Native American scouts, scientists, astronomers, cartographers, soldiers, ambulance teams, ox and mule teams and the teamsters that drove them.

The Canadian Border set documents the expedition to map the boundary between Canada and the United States from 1872 to 1876. It was a joint project by participants from the United States Northern Boundary Commission, Royal Engineers from the British North American Boundary Commission, Canadian First Nations and Native American scouts, scientists, astronomers, cartographers, soldiers, ambulance teams, ox and mule teams and the teamsters that drove them.  The pictures convey how isolated this longest continuous boundary between two countries was even decades after it was formally drawn at the 49th parallel.

The pictures convey how isolated this longest continuous boundary between two countries was even decades after it was formally drawn at the 49th parallel.