A medieval bronze jug of great rarity and historical significance stolen from a museum in Luton, Bedfordshire, England this May has been found by the Bedfordshire police. The Wenlok Jug was stolen in a smash-and-grab burglary the night of May 12th from the Stockwood Discovery Centre. At 11:22 PM, the thief, his face wrapped with a scarf to stymie the CCTV cameras, climbed the museum’s fence, broke down the door and used a drain cover to smash through the half-inch thick laminated glass and polycarbonate compound of the display case. He took the jug and ran.

A medieval bronze jug of great rarity and historical significance stolen from a museum in Luton, Bedfordshire, England this May has been found by the Bedfordshire police. The Wenlok Jug was stolen in a smash-and-grab burglary the night of May 12th from the Stockwood Discovery Centre. At 11:22 PM, the thief, his face wrapped with a scarf to stymie the CCTV cameras, climbed the museum’s fence, broke down the door and used a drain cover to smash through the half-inch thick laminated glass and polycarbonate compound of the display case. He took the jug and ran.

The museum’s insurance company offered a reward of £25,000 for the jug’s safe return because there was immense concern that the burglar planned to sell the 13-pound bronze artifact simply for its scrap value, a mere £20 ($32). The value to the museum was inestimable, both because of its market price and because of its national and regional importance. It is one of a very few datable medieval bronze jugs to bear the maker’s mark of an English bronze founder, possibly a bell founder, although the exact mark has not been found among extant medieval bells yet.

The tankard is a foot tall and is decorated with coats of arms, including Plantagenet royal arms used between 1340 and 1405 and East Anglian arms, probably relating to the foundry. There are other royal and noble symbols — crowns, badges — decorating the jug, plus a dedication to “MY LORD WENLOK” inscribed all in capitals around the bottom half. There are two possible candidates for the Lord Wenlok in question. One is William Wenlock, Archdeacon of Rochester and canon of King’s Chapel, Westminster and of St. Paul’s Cathedral, who died in 1391 and is buried under St. Mary’s Parish Church of Luton. He wasn’t a lord in the sense of having the official title, but he was an important figure in local life and in the church hierarchy, so he could have been referred to as a lord for jug purposes.

The tankard is a foot tall and is decorated with coats of arms, including Plantagenet royal arms used between 1340 and 1405 and East Anglian arms, probably relating to the foundry. There are other royal and noble symbols — crowns, badges — decorating the jug, plus a dedication to “MY LORD WENLOK” inscribed all in capitals around the bottom half. There are two possible candidates for the Lord Wenlok in question. One is William Wenlock, Archdeacon of Rochester and canon of King’s Chapel, Westminster and of St. Paul’s Cathedral, who died in 1391 and is buried under St. Mary’s Parish Church of Luton. He wasn’t a lord in the sense of having the official title, but he was an important figure in local life and in the church hierarchy, so he could have been referred to as a lord for jug purposes.

The other is his great-nephew John, the first and only official Lord Wenlock, who fought and served under every king from Henry V to Edward IV. He was Chief Butler of England from 1461 to 1469, so the Wenlok Jug could well have been used to serve royalty. He was a Member of Parliament for Bedfordshire throughout the 1430s and 1440s, was High Sheriff of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire in 1444 and was elected Speaker of the House in 1455. His family seat was Someries Castle in  Luton which, since he changed sides twice during the Wars of the Roses, was forfeited to the crown after he died fighting (not very well, by some accounts, which claim he was killed by his commanding officer the Duke of Somerset for failing to press forward in support of him) for Henry VI at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471.

Luton which, since he changed sides twice during the Wars of the Roses, was forfeited to the crown after he died fighting (not very well, by some accounts, which claim he was killed by his commanding officer the Duke of Somerset for failing to press forward in support of him) for Henry VI at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471.

Both Wenlocks lived in Luton. The family bought the Manor of Luton in 1377 and lived there until John built Someries. Their names are on the town’s medieval guild register, and there’s a Wenlock Street in town. St. Mary’s Church also has a Wenlock Chapel with a stained glass window depicting Lord Wenlock in his knightly finery.

There are only two other medieval bronze jugs like it known to exist. One is in the British Museum, the other in the Victoria and Albert. They differ in size, color and decorative details, but they all share a number of characteristics. They’re the same pot-bellied shape, although the British Museum piece looks quite different because it’s the only one of the three to have retained its lid. The other two had lids originally, but only the hinges are left now. All three inscriptions say different things, but they’re done in similar, and may I say awesome, Lombardic-style lettering. They all bear the same age royal arms (1340-1405).

There are only two other medieval bronze jugs like it known to exist. One is in the British Museum, the other in the Victoria and Albert. They differ in size, color and decorative details, but they all share a number of characteristics. They’re the same pot-bellied shape, although the British Museum piece looks quite different because it’s the only one of the three to have retained its lid. The other two had lids originally, but only the hinges are left now. All three inscriptions say different things, but they’re done in similar, and may I say awesome, Lombardic-style lettering. They all bear the same age royal arms (1340-1405).

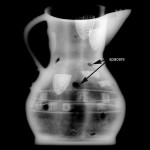

Even under the surface the three pieces show themselves to be related. A study of the three done by the British Museum found that they are made of the same alloy of copper, tin and lead known as leaded bronze. This was a popular material, but the jugs have the same impurities in the metal which suggests all three were cast at the same foundry. X-rays show that they were manufactured using the same technique — molten bronze poured into a mould with a front part, a back part and a core — which again was popular at the time. Unusual, however, was the use of metal spacers inside the moulds

Even under the surface the three pieces show themselves to be related. A study of the three done by the British Museum found that they are made of the same alloy of copper, tin and lead known as leaded bronze. This was a popular material, but the jugs have the same impurities in the metal which suggests all three were cast at the same foundry. X-rays show that they were manufactured using the same technique — molten bronze poured into a mould with a front part, a back part and a core — which again was popular at the time. Unusual, however, was the use of metal spacers inside the moulds that ensured the metal would flow freely between the outer casing and the core. All three jugs used these spacers.

that ensured the metal would flow freely between the outer casing and the core. All three jugs used these spacers.

The Wenlok Jug is the smallest of the three but bears the earliest maker’s mark. It’s also the most recent discovery. Nobody knew it existed until it was found in a cellar at Easton Neston, Northamptonshire, the stately home of Lord Alexander Hesketh which he sold to a Russian retail store magnate in July 2005. Sotheby’s auctioned off some of the contents in May of that year, the Wenlok Jug among them. It was purchased at that auction by a London dealer for £568,000 ($920,000). In October 2005, the dealer sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for £750,000 ($1,200,000).

Given its extreme rarity, its connection to two similar pieces at the two top museums in the country, the royal arms and the medieval maker’s mark, the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest run by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council declared it of national importance and outstanding significance for the study of medieval metallurgy. Culture Minister David Lammy promptly put a temporary export ban on the jug. The deal with these export bans is if a museum in-country can come up with the same amount of money the foreign entity spent on the purchase, then the local museum gets to buy it.

Given its extreme rarity, its connection to two similar pieces at the two top museums in the country, the royal arms and the medieval maker’s mark, the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest run by the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council declared it of national importance and outstanding significance for the study of medieval metallurgy. Culture Minister David Lammy promptly put a temporary export ban on the jug. The deal with these export bans is if a museum in-country can come up with the same amount of money the foreign entity spent on the purchase, then the local museum gets to buy it.

The Luton Council’s museum service, anxious to secure a masterpiece with such a close connection to the city for themselves and for the nation, stepped up to the plate. In the world of museums, it doesn’t get more David and Goliath than this. The Luton museum’s total yearly acquisition budget is £2,500 ($4,000). The Met spent $36.5 million on art purchases between June 2010 and June 2011, and that’s just a fraction of its overall acquisitions endowment of $632 million.

By hook and by crook, Luton scrounged up the £750,000 it needed to buy the jug out from under the Met. The bulk came from large grants. They got £137,500 from the National Art Collections Fund and £590,000 from the National Heritage Memorial Fund. They raised another £20,000 in donations from museum supporters, individuals, local organizations and small trusts. Throw in the museum’s annual acquisition budget and that makes exactly £750,000. They secured the Wenlok Jug at the end of February 2006, and in May it went on display at the Wardown Park Museum.

In 2008 it was moved to the newly constructed Stockwood Discovery Centre where it remained on display until the burglary earlier this year. The Bedfordshire police have been investigating the crime ever since it happened, and their doggedness has now paid off. They discovered the purloined jug on the morning of Monday, September 24th at a home in Tadworth, Surrey. Officers arrested two people at the scene. One has been charged with handling stolen property and the other is now out on bail pending further investigations. Museum experts have examined the jug today and confirmed it is the authentic artifact.

Police haven’t closed the investigation — they are still asking the public for any information they might have about the theft — but the Wenlok Jug is back home. The relief at the museum must be palpable. There was no replacing this piece. Even if they had the money, which obviously they do not, there simply isn’t another one like it.