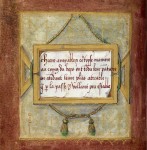

A recent addition to the British Library’s most excellent collection of digitized manuscripts is a valentine that puts contemporary efforts to shame. Written by Pierre Sala around 1500, the Petit Livre d’Amour (Little Book of Love) is a 5-inch by 3.7-inch book of poems and prose that he hand-wrote with gold ink on purple parchment and had professionally illuminated as a gift for his lover Marguerite Builloud. He even had a wood and leather carrying case made with rings on the edges so his lady love could hang it from a chain on her girdle.

A recent addition to the British Library’s most excellent collection of digitized manuscripts is a valentine that puts contemporary efforts to shame. Written by Pierre Sala around 1500, the Petit Livre d’Amour (Little Book of Love) is a 5-inch by 3.7-inch book of poems and prose that he hand-wrote with gold ink on purple parchment and had professionally illuminated as a gift for his lover Marguerite Builloud. He even had a wood and leather carrying case made with rings on the edges so his lady love could hang it from a chain on her girdle.

Pierre Sala was a renown humanist, author, cook, personal valet and equerry to King Louis XII. Born and raised in Lyon, a center of the French Renaissance, his writings are important transitional works in the shift from the scriptural, patristic approach to scholarship of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance revival of classical philosophy and secular sources of knowledge. He wrote about the lives of Greek philosophers, collections of ancient aphorisms, histories, treatises and of course, romances and poetry.

He was also something of an accidental archaeologist and antiquities collector. When he built his house on the hill of Fourvière in the center of Lyons in 1514, he unearthed a large number of Franco-Roman remains from when the city was known as Lugdunum. This collection was so impressive the king came to visit it like a tourist in 1522. Pierre even named the house Antiquaille after them.

He was also something of an accidental archaeologist and antiquities collector. When he built his house on the hill of Fourvière in the center of Lyons in 1514, he unearthed a large number of Franco-Roman remains from when the city was known as Lugdunum. This collection was so impressive the king came to visit it like a tourist in 1522. Pierre even named the house Antiquaille after them.

By then, he had sealed the deal with Marguerite. Perhaps this book helped. It is replete with references to the two of them. M and P are carved into the stylized floral pattern on the wooden cover. Their initials, drawn out of crossed compasses, decorate the pages like in a middle schooler’s Trapper Keeper. (I am aware I just seriously dated myself there). The poems and illustrations are all about love, of course, but not necessary mushy expressions thereof. The alternative name of the volume is “The Enigmas of Love” and the hardships of love, the obstacles, the dangers, are the dominant theme of the 12 drawings and the quatrains they illustrate.

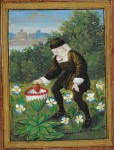

Pierre starts off telling Marguerite that he wants to put his heart inside this daisy (Marguerite meaning daisy in French), that his thoughts will always be with her. The drawing opposite depicts a man putting his heart into daisy. His facial features are very basic, deliberately left so by the illustrator, a Parisian artist known as the Master of the Chronique scandaleuse, so another artist could fill in the details to make him look like Pierre. That artist was probably Jean Perréal, a painter in the employ of the French royal family who was a personal friend of Pierre’s. Perréal never did in fill the face, but he went on to make the rather dreamy portrait of Pierre at the end of the book.

Pierre starts off telling Marguerite that he wants to put his heart inside this daisy (Marguerite meaning daisy in French), that his thoughts will always be with her. The drawing opposite depicts a man putting his heart into daisy. His facial features are very basic, deliberately left so by the illustrator, a Parisian artist known as the Master of the Chronique scandaleuse, so another artist could fill in the details to make him look like Pierre. That artist was probably Jean Perréal, a painter in the employ of the French royal family who was a personal friend of Pierre’s. Perréal never did in fill the face, but he went on to make the rather dreamy portrait of Pierre at the end of the book.

The daisy allegory is followed by a man playing blind man’s bluff with three ladies, with the accompanying poem expressing his hope that if he can catch at least one of them, she won’t escape for a year. The next poem urges caution in Italian but recommends he not despair even though there are no assurances. The drawing across from it is of a solitary table with a candle burning on top.

The daisy allegory is followed by a man playing blind man’s bluff with three ladies, with the accompanying poem expressing his hope that if he can catch at least one of them, she won’t escape for a year. The next poem urges caution in Italian but recommends he not despair even though there are no assurances. The drawing across from it is of a solitary table with a candle burning on top.

The cautionary tales and juxtapositions — a wise man painting a fool, a pilgrim and a beggar illustrating the proverb “don’t limp in front of a lame person,” a man carrying a man on his shoulders while trampling another man on the ground illustrating the proverb “trampling on one man to help another” — continue through to the end.

The cautionary tales and juxtapositions — a wise man painting a fool, a pilgrim and a beggar illustrating the proverb “don’t limp in front of a lame person,” a man carrying a man on his shoulders while trampling another man on the ground illustrating the proverb “trampling on one man to help another” — continue through to the end.

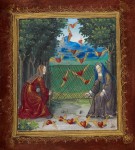

My favorite is two women trying to catch flying hearts with a net. The quatrain describes the ladies as Friendly Expression and Courteous Manner who have stretched out their net to trap the unstable hearts that pass by. The best thing about that is the poem doesn’t spell out the word “heart.” It’s a little <3 drawing, a Renaissance emoticon!

We don't know if she ever wore it like a hipster chain wallet, but Marguerite must have liked it, or at least not hated it too much, because she and Pierre were married and lived together at Antiquaille until his death in 1529.

My favorite is two women trying to catch flying hearts with a net. The quatrain describes the ladies as Friendly Expression and Courteous Manner who have stretched out their net to trap the unstable hearts that pass by. The best thing about that is the poem doesn’t spell out the word “heart.” It’s a little <3 drawing, a Renaissance emoticon!

We don't know if she ever wore it like a hipster chain wallet, but Marguerite must have liked it, or at least not hated it too much, because she and Pierre were married and lived together at Antiquaille until his death in 1529.