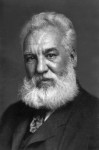

Two years after successfully recovering six experimental early recordings Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory Association stored at the Smithsonian in the late 19th century, researchers at the Library of Congress and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California have found the first and only known recording of Alexander Graham Bell’s voice. He’s reciting a long list of numbers, dollar amounts and concludes:

Two years after successfully recovering six experimental early recordings Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory Association stored at the Smithsonian in the late 19th century, researchers at the Library of Congress and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California have found the first and only known recording of Alexander Graham Bell’s voice. He’s reciting a long list of numbers, dollar amounts and concludes:

This record has been made by Alexander Graham Bell and in the presence of Dr. Chichester A. Bell on the 15th of April 1885 at the Volta Laboratory 1221 Connecticut Avenue, Washington D.C. In witness whereof, hear my voice. Alexander Graham Bell.

[audioplayer file=”http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/AGB.mp3″ titles=”Alexander Graham Bell sound test 1885″]

The project began in 2011 after National Museum of American History curator Carlene Stephens read about the Berkeley Lab’s success in recovering sound from damaged and unreadable historical recording media using optical scanning technology. The museum is custodian of a vast collection of 200 early audio recordings made by Alexander Graham Bell, his cousin Chichester Bell and their associate Charles Sumner Tainter during their time experimenting with new recording technology. The company they founded, Volta Laboratory Association, only lasted from 1881 to 1886, but during that brief period they worked with an astounding variety of technologies.

They weren’t all original inventions. Some of the work Bell et al did was on pre-existing technology that was in its infancy. They experimented and developed it far beyond their creators’ work. The results were significant milestones in the history of audio technology. Their laterally cut discs were early versions of the format which became the industry standard for the 78/45/33 RPM discs some of us old people still remember. They also pioneered the creation of a system of master recordings coupled with mass production stamping and developed photographic discs, the principle that would later be put to work in optical film soundtracks.

They weren’t all original inventions. Some of the work Bell et al did was on pre-existing technology that was in its infancy. They experimented and developed it far beyond their creators’ work. The results were significant milestones in the history of audio technology. Their laterally cut discs were early versions of the format which became the industry standard for the 78/45/33 RPM discs some of us old people still remember. They also pioneered the creation of a system of master recordings coupled with mass production stamping and developed photographic discs, the principle that would later be put to work in optical film soundtracks.

The Volta partners stored these important early recordings, devices and notes at the Smithsonian almost as soon as they produced them in case they needed evidence of their work for patent purposes. None of the recordings in the Volta collection can be played today because the players don’t exist/work and even if they did, the recordings themselves are too damaged to be run through the wringer of those early machines. Imagine how frustrating it must be for a museum to have hundreds of historically significant documents they can’t read.

Optical scanning solves the problem because it doesn’t touch the delicate surface of recordings at all. It scans them using a specially designed machine which creates a high-resolution digital map of the medium surface. The map is then processed to remove scratches and skips, and software reproduces the audio content in a digital sound file.

The pilot program focused on scanning six of the Volta recordings on different media including a variable density photo disc, a green wax vertical cylinder cut on brass and beeswax on composition board. Since the pilot, donations from private and public sources have allowed Berkeley to work on another three recordings.

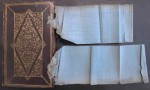

The first one, a wax on composition board disc, has an inscription on the wax that looked very promising.

The first one, a wax on composition board disc, has an inscription on the wax that looked very promising.

Record made April 15, 1885

by A.G.B. and C.A.B.

to test reproduction of numbers

Since the museum had a transcript in Alexander Graham Bell’s hand of a recording of many numbers done on April 15th, 1885, and concluding  with a signoff by the inventor, they had reason to hope that this disc might contain the voice of the man himself. Once the recording was recovered and found to match the transcript exactly, it was confirmed: this is the voice of voice-transmission icon Alexander Graham Bell.

with a signoff by the inventor, they had reason to hope that this disc might contain the voice of the man himself. Once the recording was recovered and found to match the transcript exactly, it was confirmed: this is the voice of voice-transmission icon Alexander Graham Bell.

The third of the newly deciphered recordings is also notable. It’s one of the earliest in the Volta Laboratory collection, a highly modified Edison phonograph Bell dubbed the graphophone. Made in 1881, it includes both the recording — in wax on a metal cylinder — and the player — a mandrel attached to a hand-cranked rotator which turns the cylinder.

Recorded on the cylinder is none other than Alexander Melville Bell, Alexander Graham’s father. Melville was an expert in acoustic phonetics and elocution. He invented a writing system called Visible Speech to help teach the deaf to speak. His interests in acoustics and elocution shine through in the absolutely charming recording he made in September of 1881.

Recorded on the cylinder is none other than Alexander Melville Bell, Alexander Graham’s father. Melville was an expert in acoustic phonetics and elocution. He invented a writing system called Visible Speech to help teach the deaf to speak. His interests in acoustics and elocution shine through in the absolutely charming recording he made in September of 1881.

[audioplayer file=”http://www.thehistoryblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Alexander-Melville-Bell.mp3″ titles=”Alexander Melville Bell 1881″]

[Trills] There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy. [Trill] I am a graphophone, and my mother was a phonograph.

That last line slays me. Throw in a smell of elderberries and it would be downright Pythonesque. Adorable.